Solar cookers are not a new idea. Designers as far back as the 19th century recognized the potential of the sun's energy to provide heat for cooking and other purposes and designed appropriate tools to harness it.[1]It is indeed likely that solar energy was used for cooking long before then.

Solar cookers have many potential benefits, both to their user and to the environment. A frequently cited advantage of solar cookers is that they reduce users' dependence on fuel sources for cooking. This reduction has economic benefit to the user by reducing their expenditure on fuel and also environmental benefit by reducing deforestation (in regions where wood is used as a cooking fuel) and release of combustion products into the atmosphere. Because a good deal of wood-based cooking is performed indoors with poor ventilation, solar cooking also has the potential to reduce smoke inhalation and related health difficulties.

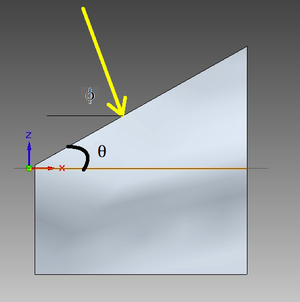

Due to its long history and many enthusiastic proponents, solar cooking already possesses a large amount of design information. This project was intended to complement existing designs by focusing on a very specific parameter: the cooker window angle.

Solar cookers are in extensive use. See Solar Box Cookers for more information.

Cultural Issues[edit | edit source]

As always with Appropriate Technology, close attention to cultural issues is extraordinarily important. Several authors have commented on cultural issues related to solar cooker technology transfer. Ramon Coyle[2] pointedly begins his article by discussing a topic often overlooked in discussions of cultural issues related to technology transfer: the culture of the Western promoters themselves. Ramon observes that, especially in the United States, the dominant culture encourages great optimism and a narrow worldview and does not value humility and patience. According to Ramon, optimism "may tempt US-based solar cooker promoters to launch grand schemes with short time frames and too little research, planning and resources."

Local cultural appreciation is of course also important. Bergler et al. provide the anecdotal perspectives of three families as a means to examine solar cooker adoption.[3] One of the families lives in rural India and cooks on an outdoor wood, dung, or chaff-burning stove twice a day: once at 11 am and once at 5 pm. Another family lives near an urban area of Guatemala and has access to a friend's improved stove that can burn almost anything and is located indoors. They take their midday meal at 1 pm and their evening meal, which contains a lot of fried food, at 6 pm. These stories are intended to illustrate some potential differences in situation that could have a bearing on solar cooker adoption. The family that cooks indoors is more likely to notice the benefits of solar cooking in terms of air quality than the family that cooks outdoors. The family that consumes fried foods in the evening might struggle with a solar box cooker that does not achieve temperatures high enough for frying. The specific times of day when the families do their cooking has an implication on cooker selection.

Solar Cooker Designs[edit | edit source]

Solar cooker designs can be broadly grouped into three categories:[4]

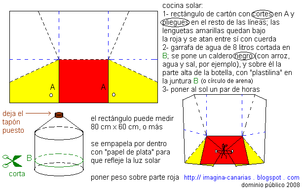

- Box cookers

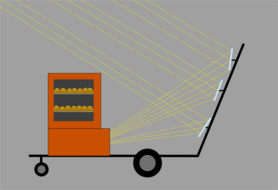

- Curved concentrator cookers

- Panel cookers

Box cookers use the greenhouse effect to create a high temperature enclosure.[5] Box cookers do not rely on high degrees of concentration, but require good insulation in order to maintain elevated temperatures in a relatively large volume. Curved concentrator cookers use a reflective surface, often parabolic, to collect light and focus it down to a small area. Cookers based on concentrators are often able to achieve much higher temperatures than box cookers, albeit in a smaller area. Panel cookers employ elements of the other two types, often featuring foldable panels and glass or plastic to create a greenhouse effect.

Existing Designs[edit | edit source]

There are a large number of solar cookers designs available freely on the internet. Some of these can be found on Appropedia. The Solar Cooking Wiki, run by Solar Cookers International, is another repository.

On Appropedia[edit | edit source]

- A comprehensive design for a parabolic cooker with a rig to help with focusing

- A parabolic design using tin can components as reflectors

- An interesting design for a parabolic concentrator cooker that uses sheet aluminum riveted to a satellite dish.

- A review of solar cooking that links to several external designs

Other free designs[edit | edit source]

- CooKit, designed by Solar Cookers international, is a panel cooker that has become popular

- Matt West has built solar cookers using, among other things, an old barbeque and a deep freezer

In light of the availability of these designs, the goal of the project was set not to provide yet another viable solar cooker design, but rather to study a particular aspect of solar cooker design to determine whether a more optimal design was available.

Project Motivation[edit | edit source]

A common trend in many discussions of the cultural appropriateness of solar cooking is that the times at which people cook their food vary considerably from location to location. It is certainly not the case that most families cook their primary meal of the day at noon, or whenever the sun is closest to zenith at the latitude in question. It is likely that there exists an optimal window angle for a solar cooker that would allow it to achieve maximum temperature at a particular point during the day.

Ideally, a cooker could be designed to have a variable window angle, but this would be non-trivial to implement and would introduce another failure mode into the solar cooker. Therefore, it has been assumed that most solar cookers have a fixed window angle. This assumption leads, for example, to a tradeoff between optimal angles at one cooking time vs. another, or at one latitude vs. another.

Project Goal[edit | edit source]

Given all of the above, the aim of the project was set to determine whether an optimal window angle could be found that would allow cooking in the morning and during the afternoon in as a wide a latitude band as possible. In order to accomplish this goal, a simulation system was designed in Java to predict cooker temperatures under different conditions.

Model Theory[edit | edit source]

Thermodynamic Analysis[edit | edit source]

The solar cooker was modeled using a one dimensional thermodynamic analysis that accounted for conduction and convection. The methods used to model both effects are discussed in detail below.

Convection[edit | edit source]

The general problem of convection is to understand how heat is transferred between a (generally) moving fluid and another body. The rate of heat transfer is proportional to the difference in temperature between the two bodies in question, as well as a proportionality h, known as the convection coefficient.[6]

Air flowing over a flat plate forms a boundary layer that grows thicker with distance downstream from the plate edge.[7] Fluid in the boundary flows at a reduced velocity relative to the plate compared with the free stream. Also, temperature gradients exist in the boundary layer, allowing for the emergence of a steady-state temperature Ts at the surface of the plate and a different steady state temperature in the free stream. The rate of heat transfer via conduction is heavily dependent on the temperature gradient at the surface of the plate, as shown below.

Since the temperature gradient varies strongly with position along the plate, an average value must be calculated in order to calculate the total heat flow rate. In combination with a number of nondimensional relations, the above allows the calculation of the dependence of the mean convection coefficient on properties of the flow. Incropera et al.[6]determined that the convection coefficient could be calculated as follows:

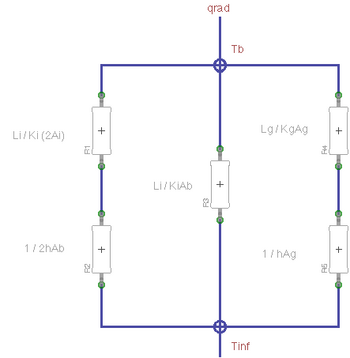

Thermal Resistance Method[edit | edit source]

Making the simplifying assumption that all conduction and convection processes are one dimensional, it is possible to apply an analogy with electric circuits to solve for the steady-state temperature in the cooker. In the analogy, heat flow corresponds to electric current, temperature corresponds to electric potential and the thermal resistance corresponds to electric resistance. The thermal resistance of an element depends on the type of heat transfer process (conductive, convective, radiative) and geometric factors. Thermal resistances for conduction and convection are given below.[6]

The circuit describes three parallel paths between the inside of the cooker (assumed to be at thermal equilibrium temperature Tb) and the outside (assumed to be at equilibrium temperature ). The path farthest to the left (path A) represents conduction through the insulating walls of the cooker and radiation to the surrounding air. The factor of two is present as this path represents conduction through two separate sides of the cooker. The center path (path B) represents conduction through the insulating wall directly to the ground. The right hand path (path C) represents conduction through the glass surface and convection from this surface.

The total resistance of the network is given below in terms of the resistances of paths A, B and C, and the temperature of the cooker is given in terms of the total resistance, qrad and the outside temperature.

It is acknowledged that the aforementioned analysis presents a simplified view of the heat transfer occuring in the system. The assumption of one-dimensional heat transfer, while likely valid at the center of each surface, breaks down where the surfaces intersect. Also, complexities in the geometry of the device make it difficult to apply even this simplified model. In reality, the heat transfer characteristics would depend on the orientation of the cooker with respect to the mean flow direction. However, this characteristic was considered unimportant and an average taken in order to eliminate dependence on the orientation of the cooker. Despite its drawbacks, this model still allows for an estimation of the temperatures achieved in the cooker under different conditions.

Radiation[edit | edit source]

In designing the model, the effects of radiation were largely ignored, as it was assumed that the effects would be negligible for the temperatures reached by the solar cooker. This, however, may not be the case.

Radiation effects can be attributed to the Stefan-Boltzmann law given below. The Stefan-Boltzmann law relates the total power radiated by a surface to its temperature. The radiative power is also related to the emissivity of the material (the extent to which it deviates from an ideal blackbody) and to the surface area of the material. Emissivities of common construction materials (brick, wood, glass, etc.) range from about 0.8 to 0.94.[8]

Given an outer surface temperature of 80 °C and an emissivity of 1, radiation from the surface would amount to 880 W/m2, a considerable amount relative to the solar constant of 1000 W/m2. Emissivity should have been taken into account in the model.

Sun Elevation[edit | edit source]

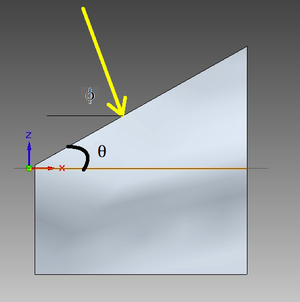

The sun's position in the sky can be specified by two angles: the azimuth angle, specifying the direction to the normal to the plane of the horizon that intersects the sun (this is equivalent to the compass direction towards the sun) and the elevation angle, specifying the angle the sun's rays make to the plane of the horizon. Since cookers were assumed to be maneuverable enough to be rotated as the azimuth angle varies, the elevation angle was treated as the only solar parameter of interest. The solar elevation angle can be calculated as shown below:[9]

where

- is the Elevation angle

- is the hour angle, in the local time

- is the current sun declination (angle between the equatorial plane and sun's rays)

- is the local latitude

The declination angle is easily calculated from the calendar date:

where

- is the day of the year

- is the tilt angle of the Earth's axis

The hour angle can also be calculated from the time of day via a reasonably simple formula. See this article on the hour angle for more information.

Fresnel Reflection[edit | edit source]

The effect of the sun's rays striking the solar cooker at different angles is extremely important to this modeling exercise. The reflective behaviour of these rays was modeled using the Fresnel equations shown below.[10]

The above equations give reflection coefficients for light crossing a boundary between two media. Rs gives the coefficient for light polarized perpendicular to the interface and Rp gives the coefficient for light polarized parallel to the interface. R gives the coefficient for unpolarized light, where n1 and n2 are the indices of refraction of the first and second media, respectively and is the angle of incidence. Wikipedia provides a useful diagram of the variables here.

In order to deal with the two boundaries (air - glass and glass - air), the Fresnel equations were simply applied twice. The angle of refraction at the first interface was calculated from Snell's law and this angle was accounted for when calculating R at the second interface. No second-order reflections were taken into account in calculating the transmitted intensity, which was given by the equation below.

Simulation software[edit | edit source]

Simulation software was written in Java. Links to simulator files are provided below:

Overview and Limitations[edit | edit source]

There are many parameters associated with the solar box cooker model. However, the model was intended to demonstrate the relationship between five critical variables associated with cooker temperature:

- Latitude

- Time of Day

- Day of Year

- Window Angle

- Cooker Temperature

Four of these variables are independent, so the temperature reached by the cooker can be determined by specifying the latitude, Time of Day, Day of Year and Window Angle. To produce a useful tool, the software was designed to produce three-dimensional plots with Window Angle on the x-axis, Latitude, Day of Year or Window Angle on the y-axis and Cooker Temperature on the z-axis.

It should be noted from the outset that the quantitative predictions made by the model are not accurate. Initially, the various parameters associated with heat transfer in the system were selected as reasonably as possible (most of these assumptions are visible in the Input File). However, based on these values, the model output extremely large values for the cooker temperature. Thus, a single parameter was adjusted in order to scale the results to a more reasonable range. The parameter so adjusted was the optical efficiency, the fraction of light entering the box (having already been partially reflected/absorbed by the glass) that is re-emitted by the box walls as infrared radiation and becomes trapped inside the box. Kumar has found the optical efficiency of a solar box cooker to be approximately 69%.[11] In order to scale results for full irradiance (1000 W/m2 incident) to a temperature of 100°C, in this model the efficiency was set to 2%.

Input File[edit | edit source]

The Input File allows the user to specify the parameters and variables of interest to the model. The Mode selects the type of plot to be generated:

- Mode 1: Window Angle on the x-axis (deg), Time of Day on the y-axis (hours), Cooker Temperature on the z-axis (°C)

- Mode 2: Window Angle on the x-axis (deg), Latitutde on the y-axis (deg), Cooker Temperature on the z-axis (°C)

- Mode 3: Windown Angle on the x-axis (deg), Day of Year on the y-axis (days), Cooker Temperature on the z-axis (°C)

Evidently, the input file allows the user to over-specify the model. For example, in all modes, the Window Angle is varied from 0° to 60° in order to produce a plot. Therefore, specifying a window angle has no effect on predictions. For another example, specifying the Time of Day has no effect in Mode 1, but does have an effect in Modes 2 and 3. The dTGMT variable represents the offset to universal time, and is used in calculating the angle of the sun for different times of day as measured in a particular time zone. dTGMT for the Kingston area is -5.

Output[edit | edit source]

The program outputs three files: xout.txt, yout.txt and out.txt. Each file contains an m x n matrix. out(i,j) represents a particular cooker temperature, corresponding to the position (xout(i,j), yout(i,j)). The coloured plots in this section were created by plotting this data with Matlab's pcolor command [pcolor(xout,yout,out)], but the data could be visualized equally well with an open-source software package.

Discussion and Results[edit | edit source]

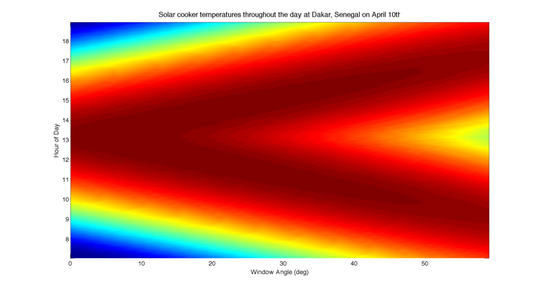

The plot at right shows the cooker temperature for various window angles at various times of day for Dakar, Senegal. The results are in line with intuitive expectations: lower window angles lead to a higher cooker temperature towards midday and higher angles lead to higher cooking temperatures in the morning and afternoon. It is interesting to note that it is possible to achieve just as high a temperature at 10:30 in the morning as it is to achieve at 1 in the afternoon, a different window angle is simply required.

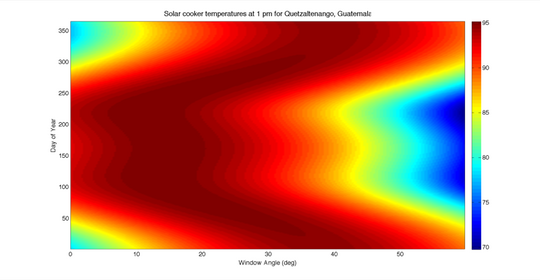

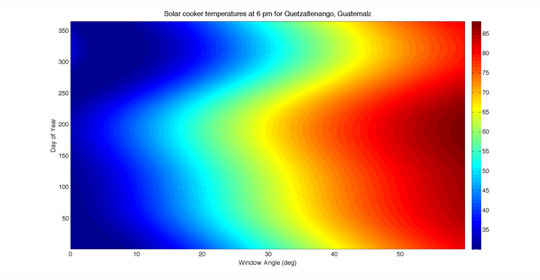

The plots below were inspired by Bergler et al.'s case study of solar cooker users in different locations around the world. The first two plots represent temperatures attainable by cookers in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala at 1 pm and 6 pm at different days throughout the year. These times correspond to stated preferred cooking times by residents who participating in the study. At 1 o'clock, it is clear that an optimal window angle would be about 21°. This would ensure temperatures in excess of 90 °C in the cooker for the entire year. However, a 21 ° angle at 6 pm is far less ideal and would result in a maximum temperature of only 60 °C. Choosing an acceptable tradeoff between these two angles would be difficult because of the resulting low temperatures, and it is likely that in this region, a reflector would need to be used to increase the temperature of the cooker.

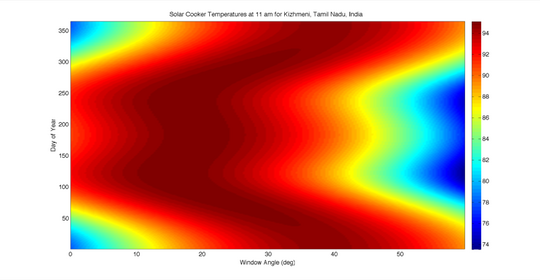

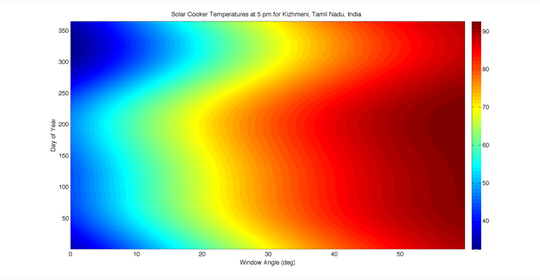

The situation for Kizhmeni, a village in Tamil Nadu, India, is somewhat more conducive to solar cooker selection. The two plots show the same basic forms as those in Quetzaltenango, but it appears that a window angle of approximately 35 ° would result in temperatures not below 90 °C at 11 am and temperatures of around 80 °C for most of the year at 5 pm.

|

|

|

|

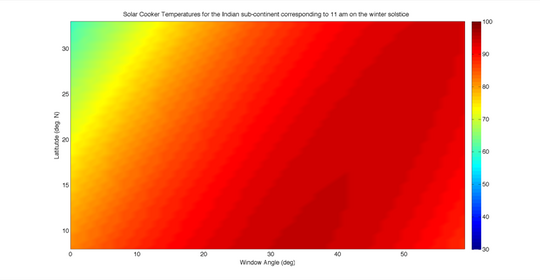

The plot to the right was created to motivate a possible use for this model: optimizing for window angle across multiple latitudes. As is clear from the plot, an angle of 35 ° which we had selected for Kizhmeni (Southern latitudes in figure at right) ensures that temperatures do not drop below 80 °C when used across the subcontinent. This conclusion needs verifications at other locations and at other days of the year, but suggests that single window angles could be employed across relatively large latitude regions with good results.

Future Work[edit | edit source]

As has been stated, this model is not an accurate representation of a solar simulator. Temperatures predicted by the model are much too high to reflect physical conditions without artificially adjusting the optical efficiency. As was also mentioned, the model is notably lacking in its neglect to treat radiative losses from the cooker. This shortcoming needs to be addressed. Additionally, the model needs to be compared with several different box cooker designs operating under different conditions in order to make more reliable predictions, ideally employing.

According to the model, the design space is specified by 5 variables: Latitude, Time of day, Window angle, Cooker temperature, and Day of the year. A comprehensive implementation of the model would allow the user to specify design constraints in terms of any of the variables and assess the impact of these constraints on the other variables. It would also allow the user to optimize the window angle for these different design constraints.

In theory, this is not difficult to do. Practically, there are many challenges. There is a computational challenge in calculating the temperature at every point in time during the year with reasonable resolution, at every latitude, and with every possible window angle. There is a challenge in terms of how to display data with so many free variables in a useful way. A potential implementation might allow the user to specify a cutoff temperature (i.e. greater than 100°C), a time of day over which the cooker must be functioning, and a particular day of interest and then obtain a plot similar to the one below. Such a plot would be highly useful in making a design tradeoff between optimal power at a particular location and effectiveness over a large region.

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

A solar cooker simulation code was designed in order to predict cooker temperatures under various conditions with the aim of determining optimal window angles. The software successfully predicted trends in cooker temperatures, but absolute temperatures were not believable due to inadequacy of the thermodynamic model used. Results show that under certain conditions, a reasonable compromise can be made to find a window angle applicable to two desired cooking times. Specifically for the region of Tamil Nadu in India, the model suggests that a window angle of 35 ° would allow cooking at 11 am and at 5 pm with box temperatures not falling below 80 °C. The model also suggests that a single window angle may be applicable over a relatively large range of latitudes. The model needs refinement and validation against a physical box cooker. The model could also be enhanced to include the effects of reflectors.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kundapur, A., Solar box cookers - Solar Cooking. Available at: http://solarcooking.wikia.com/wiki/Box_cookers [Accessed April 4, 2010].

- ↑ Coyle, R., Solar cooker dissemination and cultural variables - Solar Cooking. Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20170927125644/http://solarcooking.wikia.com/wiki/Solar_cooker_dissemination_and_cultural_variables [Accessed April 16, 2010].

- ↑ Bergler, H. et al., 1999. Moving Ahead with Solar Cookers: Acceptance and Introduction to the Market, Eschborn, Germany: German Technical Cooperation.

- ↑ Multiple, How solar cookers work - Solar Cooking. Available at: http://solarcooking.wikia.com/wiki/How_solar_cookers_work [Accessed April 19, 2010].

- ↑ Aalfs, M., Principles of Solar Box Cooker Design - Solar Cooking. Available at: http://solarcooking.wikia.com/wiki/Principles_of_Solar_Box_Cooker_Design [Accessed April 4, 2010].

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Incropera, F.P. et al., 2007. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer 6th ed., Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Boundary layer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boundary_layer [Accessed April 16, 2010].

- ↑ Emissivity Coefficients of some common Materials. Available at: http://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/emissivity-coefficients-d_447.html [Accessed April 16, 2010].

- ↑ Honsberg, C. & Bowden, S., Photovoltaics CDROM. Available at: http://web.archive.org/web/20100801072122/http://pvcdrom.pveducation.org:80/index.html [Accessed April 16, 2010].

- ↑ Fresnel equations - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fresnel_equations [Accessed April 6, 2010].

- ↑ Kumar, S., 2004. Thermal performance study of box type solar cooker from heating characteristic curves. Energy Conversion and Management, 45(1), 127-139.

![{\displaystyle \,\sin \delta =\sin(23.45^{\circ })\sin \left[{\frac {360}{365}}(d-81)\right]\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5cebf5c3d8cdb1745bea5f07a35fbf75d35d7c06)

![{\displaystyle R_{s}=\left[{\frac {n_{1}\cos \theta _{i}-n_{2}{\sqrt {1-\left({\frac {n_{1}}{n_{2}}}\sin \theta _{i}\right)^{2}}}}{n_{1}\cos \theta _{i}+n_{2}{\sqrt {1-\left({\frac {n_{1}}{n_{2}}}\sin \theta _{i}\right)^{2}}}}}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d35b873f78b8fa55d59cb4068548c8210d3a9edb)

![{\displaystyle R_{p}=\left[{\frac {n_{1}{\sqrt {1-\left({\frac {n_{1}}{n_{2}}}\sin \theta _{i}\right)^{2}}}-n_{2}\cos \theta _{i}}{n_{1}{\sqrt {1-\left({\frac {n_{1}}{n_{2}}}\sin \theta _{i}\right)^{2}}}+n_{2}\cos \theta _{i}}}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2201a0fe047132c1990e72e10e927edab5edd205)