Reaching sustainable development goals has never been more critical given the growing calamities such as resource scarcity, human population growth and dangers of climate destabilization. In order to help solve some of the development challenges, this paper sets out to understand and outline key barriers facing organizations and researchers working in the field of appropriate technology (AT) for sustainable development, as well as to explore opportunities for an increased collaboration and adoption of open source paradigm in research and development. As such, key organizations and researchers working in the field of appropriate technology were interviewed to identify barriers to open sourced appropriate technology or OSAT. Once transcribed, the interviews were highlighted via pattern coding and content analysis, and grouped in overarching themes consisting of: i) Social Barriers; ii) Barriers to Technology; iii) Information and Communication barriers; iv) Barriers to Open Source; and v) Social and Technical Barriers.

Results of the interviews confirmed majority of literature identified barriers and also suggest that among the most pressing problems for those working in the field of appropriate technology is the need for a much better communication and collaboration between all the stakeholders to share pertinent knowledge and resources. Additional barriers discussed by the interviewees are: i) AT seen as inferior or "poor person's" technology, ii) technical transferability and robustness of AT, iv) insufficient funding, v) poor institutional support, and vi) the challenges of distance and time in tackling rural poverty. In discussion on open source and open access, the interviews show that desire to collaborate on problem solving is present, but the right tools and platforms to allow for that exchange of knowledge and improved collaboration still seems to be missing - or are not widely known.

Background[edit | edit source]

In order to identify barriers to OSAT and suggest solutions, this study aimed to interview as many key organizations and researchers working in the field of appropriate technology, as well as those involved with the open data movement. A growing number of authors agree how the field of AT can be of significant assistance in sustainable development: namely provide food and water security, health, education, as well as dignified work opportunities for world's millions (Schumacher, 1973; Jequier, 1976; Chambers, 1983; Carr, 1985; Hazeltine and Bull, 1999; Smillie, 2000; Sawhney et al., 2002; Pearce and Mushtaq, 2009; Buitenhuis et al., 2010). However, despite the potential, AT field is yet to reach critical exposure and development on a larger scale. A number of barriers has been identified as key obstacles: some are purely technical in nature, while others have roots in social, economical, geographical and political arenas, demonstrating yet once again the complex nature of the development process (Jéquier, 1976; Chambers, 1983; Carr, 1985; Hazeltine and Bull, 1990; Smillie, 2000). Literature review on the topic revealed how the most pressing issues facing AT are: the defining parameters of AT, access to stable funding, better institutional support, technological design, implementation and dissemination of AT, constraints of permanence, robustness and transferability of AT systems, as well as larger inclusion of community participation and feedback. With this data in hand, interviews were set up to confirm and extrapolate the relevance of before-mentioned barriers today.

Methodology[edit | edit source]

Data Collection

In total seventeen interviews were conducted with twenty one participants from the field of AT development and open data. The interviews followed the semi-structured 30 minute interview method as developed by Mikkelsen (1995), supplemented by informal conversational interview techniques (Babbie and Rubin, 2007). Questions included barriers to development in general, as well as barriers to the appropriate technology and open source / open access of data in research. Attempts were made to balance the types of the respondents, but time restrictions for the project limited the ability to obtain equal representation of respondents from all sectors involved in AT development. The final interview breakdown included responses from five academics working in the field of development, eight non-governmental organizations, one governmental, as well as feedback from two entrepreneurial organizations and two independent activists and researchers. The academic researchers included professors from Arizona University, Cooper Union, Hope College, St. Thomas and Western Washington University. Non-Governmental and Not for Profit Organizations participating in the interviews included: American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), the Appropedia Foundation, Appropriate Technology Collaborative (ATC), Appropriate Infrastructure Development Group (AIDG), Compatible Technology International (CTI), Digital Green and Practical Action. Governmental agency input was provided by the Canadian Crown Corporation - International Development Research Center (IDRC). The research also included feedback from the entrepreneurial sector - AYZH and Kopernik, as well as open data movement activist David Eaves and development activist Vinay Gupta.

Analysis Process

Once the University ethics board clearance was granted, prospective interviewees were contacted via e-mail or in person with an invitation to the research, outlining the background of the study, providing sample questions and the consent form. A majority of the prospective interviewees agreed to the interview, of which all but one granted the permission to record the talk, and all but one gave permission to use their name in publications. Four of the interviews were conducted in person, two were via an e-mail correspondence, while the rest were skype/ phone interviews. As per the ethics guidelines, the interview data, including audio files, transcriptions and consent forms are stored in a locked location on an encrypted disc. Once completed, the interviews were transcribed and coded for key barrier categories which were counted to assess their frequency while extrapolating themes, patterns and top barriers. To analyze the data two techniques were employed: logical and pattern coding. First, the interview responses were analyzed using logical analysis procedures based on Patton (1990), which explored emergent themes and barriers throughout the interviews and their frequency. Next, the pattern coding was employed to group summaries of data into smaller number of overarching or linked themes (Miles and Huberman, 1984). Key comments and responses were highlighted and coded via pattern grouping in regards to their relevance to social or technical barriers to AT, open access, and general development. The coded themes and their subsequent responses were then counted for frequency of use to provide numerical data and help identify the most pressing barriers.

Results[edit | edit source]

Five barrier themes to OSAT development were identified through the process of coding the interviews:

- social barriers,

- communication and information specific barriers,

- barriers to open source technology,

- barriers to technology (AT or in general), and

- social and technical barriers inter-connected.

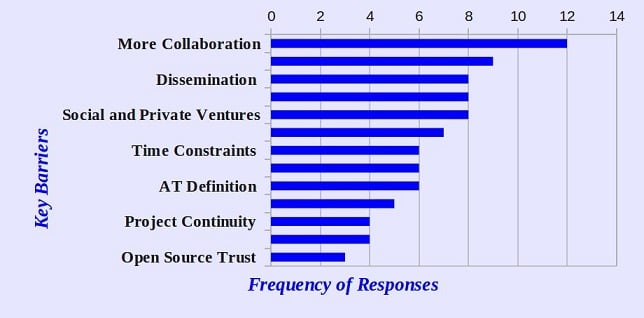

Further analysis of the coded barrier categories presented above provided a more in-depth look of key single barriers within those five categories. Figure 1 below illustrates this qualitative breakdown of specific barriers and the number of times interviewees brought up a specific key barrier. As can be seen, the most single discussed barrier (twelve respondents) was the need for better collaboration with locals, NGOs and universities to share knowledge, data and feedback so not to have to reinvent technologies and to re-learn from past mistakes. Similarly, better communication and access to knowledge was another top issue brought up by nine respondents.

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

The results of the interviews in this research confirmed a large number of literature identified barriers to appropriate technology (AT). The obstacles include a mix of technical, cultural, social, political, institutional and organizational challenges with equal bearing and importance. Some of those barriers include: i) AT seen as inferior or poor person's technology, ii) obstacles of cultural appropriateness, iii) problems of technical robustness, iv) transferability and the fit within current industrial and economic systems, v) barriers of distance and time in solving rural poverty, vi) as well as problems of stable funding and a better institutional support for AT.

In addition, interviews with some of the key organizations and researchers working in the field of AT also revealed further obstacles - mainly the need for a much better exchange of knowledge and collaboration among agencies, researchers and communities working on AT solutions. Interview respondents repeatedly focused on the need to share knowledge and resources and work in partnership. Marketing, social ventures, and business opportunities were also topics of interest for many in order to scale up and improve their development efforts. Majority of the before-mentioned barriers can in some form and shape be reduced or minimized by better linkage, feedback, collaboration and exchange of knowledge though a greater inclusion of ICTs. Collaborative online platforms are quickly becoming the backbone of many social, economic and research-related enterprises but their contribution to the field of sustainable development is yet to reach full potential. Information and communication technologies such as the Internet allow for a plethora of collaborative and open source enterprises, wikis, forums, online databases and platforms for knowledge accumulation and exchange, and hold a lot of promise for the future of development and innovation.

Discussion and interview responses on open source and open access to knowledge were also very insightful and demonstrated general receptiveness to the core principles of knowledge commons, open source and innovation through collaboration. There is already a movement toward a greater inclusion of ICTs for distributed collaborative innovation in sustainable development and AT, and this is indicative of a very positive trend. However, as the interviews revealed not everyone is participating in this open collaboration just yet. The interest and awareness of the benefits brought on by better collaborative methods is clearly there, and perhaps what is missing (or is not widely known) are the right tools and to allow for that collaboration to blossom and reach its full capacity. This topic is worth pursuing in a much greater detail given the potential of improved effectiveness and efficiency for researchers, organizations and communities working together to solve sustainable development challenges in such as climate de-stabilization, rising world populations, and resource scarcity. More needs to be done on all levels to encourage, showcase and allow for open access and open source collaboration. This includes an increased participation for the researchers and organizations, as well as communities and individuals employing the solutions.