Gas turbines, as with all areas of power production, are highly dependent on thermal efficiency to effectively produce power. There are several ways in industry to increase the thermal efficiency of a gas turbine power cycle. These methods of increasing efficiency are almost always limited by the metallurgical properties of the turbine components. The thermal efficiency of gas turbine can be greatly increased with components that are able to withstand higher working temperatures. The use of single crystal superalloy turbine blades allows for this to be possible. The single crystal turbine blades are able to operate at a higher working temperature than crystalline turbine blade and thus are able to increase the thermal efficiency of the gas turbine cycle.

Gas turbine cycles[edit | edit source]

Gas turbine power plant consists of a turbine that is connected to a compressor with a combustion chamber in between. Atmospheric air is drawn into the compressor and subsequently compressed and enters the combustion chamber. In the combustion chamber air is mixed with a fuel and combusted. This increases the temperature of the air while remaining at a constant pressure. The air now enters the turbine where expansion takes place while producing useful output work. The higher the inlet air temperature is the greater amount of useful work that is produced from the turbine.[1]

Increasing efficiency[edit | edit source]

This thermodynamic cycle is referred to as the Brayton Cycle.W The efficiency of gas turbines is given by the equation

-

Equation 1: Thermal efficiency of Brayton Cycle

-

Equation 1a: Thermal efficiency of Brayton Cycle in terms of pressure ratio

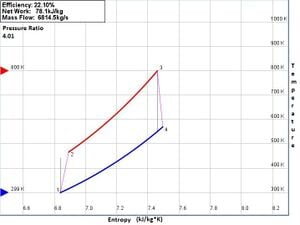

Brayton Cycles are often represented by temperature-entropy, or TS, diagrams. These diagrams show the states of the air at each point of the Brayton cycle. An example of a typical TS diagram is show in figure 1 below.

-

Fig 1: TS diagram of Brayton Cycle

-

Fig 1a: Increased pressure ratio

-

Fig 1b: Increased max temperature and pressure ratio

From the TS diagram shown in Figure 1a it can be seen that an increase in the relative pressure ratioW will in fact increase the thermal efficiency due to a decrease in the amount of heat added to the system. This is limited by the maximum temperature of the cycle which occurs at the turbine inlet. This limit causes a decrease in the overall work output of the cycle as the pressure ratio increase. To produce the same amount of output work at an increased relative pressure ratio, an increase in mass flow rate is needed which requires larger more expensive equipment.[2] There are many applications where a smaller turbine engine is needed, such as in vehicles. The thermal efficiency can be increased while also increasing the level of output work by increasing the temperature of the air at the inlet of the turbine.[1]

There are many applications where a decrease in net work produced is unacceptable. An increase in the maximum temperature of the cycle increases both efficiency and the total amount of net work produced. The increase in temperature also allows for a greater increase in the pressure ratio to further improve efficiency while maintaining a high level of net work output. This is displayed in figure 1b above. Metallurgical properties limit how high the inlet temperature of the turbine can operate at. Many methods are used to allow for turbine blades to perform under higher temperature conditions. The development of the single crystal turbine blade made of a nickel based super alloy allows for higher operating temperatures to be obtained.

Advantages[edit | edit source]

Single crystal turbine blades have the mechanical advantage of being able to operate at a much higher temperature than crystalline turbine blades. Given the ability to increase turbine efficiency with higher temperatures, the development of these blades is very beneficial. The turbine blades are able to operate at these high temperatures due to the single crystal structure and the composition of the nickel based superalloy.

CreepW is a common cause of failure in turbine blades and is in fact the life limiting factor.[3] When temperatures of a material under high stress are raised to a critical point, the creep rate quickly increases.[4] The single crystal structure has the ability to withstand creep at higher temperatures than crystalline turbine blades due to the lack of grain boundaries present. Grain boundaries are an area of the microstructure where many defects and failure mechanisms start which leads to creep occurring.[5] The lack of these grain boundaries inhibits creep from occurring in this way. Creep will still occur in single crystal turbine blades but due to different mechanisms that occur at higher temperatures. The single crystal turbine blade does not have grain boundaries along directions of axial stress which crystalline turbine blades do. This also works to increases the creep strength.

Nickel based superalloy[edit | edit source]

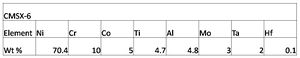

There have been several superalloys that have been used in attempting to create a single crystal turbine blade that is able to withstand the highest operating temperatures possible. These superalloys are generally nickel based and contains several other elements that all contribute to optimizing the mechanical properties of the turbine blade under high temperature conditions. The composition of each element added is constantly being tested to allow for this optimization. An example of a superalloy used for the purpose of single crystal turbine blades is CMSX6. The composition of this super alloy is shown in the table below.

Within the single crystal of the superalloy, there are two phases present, a gamma matrix and a gamma prime precipitate. The gamma prime phase needs to be greater than 50% volume fraction in the superalloy to provide the increase in creep resistance.[6] The presence of the gamma prime phase increases the mechanical strength of the turbine blade by preventing dislocation motion. The gamma prime phase has the unusual property of increasing strength as temperature increases. This is true up to 973 degrees Celsius.[3] This increase in strength cause by an increased in temperature results in the superalloy being able to operate under higher temperatures.

The lack of grain boundaries in the turbine blade allows for the superalloy being used to reduce the presence of elements that are usually used to strengthen grain boundaries, such as carbon and boron. These elements reduce the creep strength and the melting temperature of the alloy when found in more significant compositions. Without the need for significant concentrations of these elements, the single crystal turbine blade is able to maintain its strength and use at higher temperatures.[7]

Manufacturing process and crystal growth[edit | edit source]

There are several different manufacturing methods that are used in practice to create single crystal turbine blades. The manufacturing methods all use the idea of directional solidification, or autonomous direction solidification,where the direction of solidification is controlled. A common method is the Bridgman method to grow single crystals. In this method a casting furnace is used for crystal growth. In this process, a mould must first be made of the blade. Molten wax is injected into a metallic mould of the desired turbine blade and left to set and take the form of the turbine blade. The wax model is then used to create a ceramic mould to use for production of the single crystal turbine blades. When the ceramic mould is created, it is heated to raise the strength of the mould.[8] Once the mould is sufficient for use, the wax is melted out from the inside of the mould. The mould is now filled with the molten form of the nickel based superalloy. The molten superalloy contained within the mould is placed in some type casting furnace, often a vacuum induction meltingWfurnace, which uses Bridgman techniques.

Crystal growth in bridgman furnace[edit | edit source]

The furnace is set up with an area of high temperature which is above the melting temperature, controlled by heaters, and low temperature below the melting zone, with a gradient zone where the solid-liquid interface occurs. The superalloy is initially entirely within the high temperature zone in molten form. The superalloy is then lowered extremely slowly, at rates of about a few inches per hour, so that the solid liquid interface rises slowly up the mould. The superalloy solidifies from the base up. The slow rate of solidification causes grains to grow as dendritesW in the direction in which the mould is pulled from the furnace.[8] The dendrites form only as columns in the one direction because of the effect of constitutional undercooling. As the solid begins to form, a varying solute concentration is found just ahead of the solid-liquid interface. The variance in solute throughout the liquid causes a change in the equilibrium solidification temperature. At this point the temperature of the liquid is lower than the equilibrium solidification temperature causing an undercooling effect. Undercooling causes heat to be transferred from solid protrusions to the liquid promoting dendritic growth.[9] The rate at which dendrites grow is directly related to the amount of undercooling present. Dendrites that are aligned at an angle have to grow faster to keep up with the dendrites taking a more direct, vertical direction. To grow faster, a greater amount of undercooling is needed which means these angled dendrites grow further back from the solid-liquid interface.[8] Eventually the more favourable vertical dendrites overtake the angled dendrites that are further back. To remove grain boundaries from the turbine blade, a grain selector is attached to the bottom of the wax mould. The grain selector is a spiral shaped tube that is not much larger than a single dendrite grain. As the vertical dendrites grow at the base of the mould, only one dendrite will be able to fit through the spiral and eventually into the turbine blade mould. Thus once the solidification is complete, the turbine blade is created entirely from one grain and becomes a single crystal turbine blade.

Improvements on the method[edit | edit source]

The problem with the Bridgman method is that a complex, expensive casting furnace is needed to produce the desired product. Another manufacturing method has been created that takes away the need for the sample to be slowly pulled out of the furnace. This simplifies and speeds up the process making it more cost efficient. The mechanical properties are also improved as the solidification is more rapid causing a reduction in the amount of segregation amongst the sample.[10] This process uses a mould made of Al203 ceramic, which is coated with a layer that inhibits nucleation from occurring. The sample is set up so there is controlled heating keeping it molten all the way through with a water-cooled chill plate set at the base of the sample. The spiral grain selector is used in the same way in this method. The heating is turned off and as the furnace cools down, solidification begins. The layer of the mould delays nucleation from occurring until a substantial amount of undercooling is produced.[10] At this point nucleation begins at the base of the sample and dendrites form in the same way. A single dendrite passes through the grain selector and the single crystal turbine blade is produced. The controlled heating and amount of chilling at the base can be varied to optimize mechanical properties.[10]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Badran, O. O. (1999). Gas-turbine performance improvements. Applied Energy, 64(1-4), 263-273.

- ↑ Michael J. Moran', 'Howard N. Shapiro'. (2008). Fundamentals of engineering thermodynamics (6th ed.). United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Carter, T. J. (2005). Common failures in gas turbine blades. Engineering Failure Analysis, 12(2), 237-247.

- ↑ William D. Callister, J. (2007). Materials science and engineering an introduction. United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ↑ Lee S. Langston. (2006). Crown jewels. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20100705051223/http://www.memagazine.org/backissues/membersonly/feb06/features/crjewels/crjewels.html

- ↑ Szczotok, A., Richter, J., & Cwajna, J. (2009). Stereological characterization of γ′ phase precipitation in CMSX-6 monocrystalline nickel-base superalloy. Materials Characterization, 60(10), 1114-1119.

- ↑ Hino, Takehisa (Sagamihara, JP) Koizumi, Yutaka (Ryugasaki, JP) Kobayashi, Toshiharu (Ryugasaki, JP) Nakazawa, Shizuo (Suginami-Ku, JP) Harada, Hiroshi (Tsukuba, JP) Ishiwata, Yutaka (Zushi, JP) Yoshioka, Yomei (Yokohama, JP). Nickel-base single-crystal superalloys, method of manufacturing same and gas turbine high temperature parts made thereof - patent 6673308 Retrieved 11/13/2009, 2009, from http://www.freepatentsonline.com/6673308.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 H'A. Onyszko', 'K. Kubiak', 'J. Sieniawski'. (2009). Turbine blades of the single crystal nickel based CMSX-6 superalloy. Journal of Achievements in Materials and Manufacturing Engineering, 32(1) Retrieved from www.journalamme.org/papers_vol32_1/32110.pdf

- ↑ 'David A. Porter', 'Kenneth E. Easterling', 'Mohamed Y. Sherif'. (2009). Phase transformations in metals and alloys. United States: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Ludwig, A., Wagner, I., Laakmann, J., & Sahm, P. R. (1994). Undercooling of superalloy melts: Basis of a new manufacturing technique for single-crystal turbine blades. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 178(1-2), 299-303.