In the summer of 2010, a collaboration between students of Cal Poly Humboldt and the International Institute of Renewable Resources (IRRI) will seek the construction and dissemination of a biodigestion system, the Sistema Biobolsa, within the community of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas. The objective of this project is to promote the realization of further Biobolsa projects in the San Cristobal de las Casas area by constructing a successful Biodigester demonstration system in the eco-home of local builder and home designer Juan Hidalgo.

-

Team Biogas and Biodigester (photo: Lonny Grafman)

-

Team Biogas: Julia Balibrera, Gina LaBar, Garnet Empyrion, Annie Bartholomew

International Renewable Resources Institute-Mexico[edit | edit source]

"IRRI Mexico is dedicated to promoting sustainable use of natural resources. We provide education, develop new technologies, and install systems that help low income families meet their basic energy, water, and sanitation needs in a sustainable way. Our projects aim to empower families, communities, and businesses to produce their own clean energy, obtain their own water, and manage their own resources and wastes in ways that benefit them and the environment simultaneously."[1]

- Appropedia Page: International Renewable Resources Institute-Mexico

- Website: http://www.irrimexico.org

- General Information: info@irrimexico.org

- Executive Director Alex Eaton: alex

irrimexico

irrimexico org

org - Coordinator Helene Gutiérrez: helene

irrimexico

irrimexico org

org - Telephone: + (52) 55 52 56 56 86

- Instituto Internacional de Recursos Renovables

- A.C.

- 37 Amatlán, 1st Floor

- Col Condesa, Mexico D.F. 06140

IRRI's Mission

Biodigestion[edit | edit source]

In Chiapas, Mexico, mismanagement of animal waste is problematic for the health of the planet as well as its inhabitants.[3] The odors themselves can be harmful to human health, causing irritation of the eye, nose, throat, headache, nausea, vomiting.[4] Raw, or partially digested, manure retains hazardous pathogens which can be spread to humans through premature composting, agricultural run off and contamination of the water table.[5]Furthermore, surface runoff of manure contributes to the degradation of local ecology.[4]Decomposition of animal manure releases gases, such as methane, into the atmosphere that can be environmentally destructive. These gasses are byproducts of fermentation. Methane is a greenhouse gas is approximately 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide.[6]

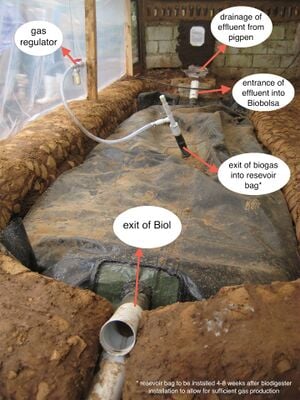

One way to mitigate these effects is to install a biodigester. Biodigestion describes the biological process by which organic matter is digested by anaerobic bacteria over the course of time. In the natural world, biodigestion occurs in a variety of anaerobic (oxygen-free) environments that include: marshes, the ocean floor, the human body, and manure. A biodigester is a system which uses the metabolism of anaerobic bacteria in order to digest animal manure producing biogas, a clean, renewable fuel source, as well as effluent, an organic fertilizer which in the case of our Biobolsa system we call Biol.[1]

The Biogas produced in a biodigester system is a key incentive. Approximately 25% of rural populations in Mexico currently use wood as a primary cooking fuel.[7] Wood as a fuel has several drawbacks: it is labor intensive to collect, it contributes to deforestation, and upon combustion poses significant respiratory risks to users.[8] The popular alternative to wood use is Liquid Petroleum (LP) gas and electricity, the both of which require elevated operational costs.[9] Biogas can be an alternative to shouldering such an economic burden by providing low cost energy and increasing energy security.[10]

Typically, biogas is composed of 55 - 65% methane, 35-45% carbon dioxide, a small fraction of hydrogen sulfide gas, and other trace gases. Of these impurities, the presence of H2S (hydrogen sulfide) is the most problematic. Although H2S constitutes less than 0.5% of the gas stream, it is extremely corrosive. Any metal equipment used within a biogas system to convert the gas to either direct heat applications (a boiler) or to more complex energy exchanges (a generator) will therefore degrade relatively quickly.[11] The larger the system, the larger the impact the presence of gaseous impurities will have on biogas production. As we are building a small, size 3 Biobolsa system,[12] the intended application of the biogas is relatively small and therefore will not require an industrial approach to gas scrubbing. In order to reduce the H2S in the biogas, our system uses a packet of non-stainless steel wool in the gas regulator; with this type of filter, the the H2S will corrode the non-stainless steel wool before it has a chance to degrade metal equipment interior to the biogas´s end-use.

Animal manure has its high macro-nutrient content. It confers considerable amounts of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous to germinating crops and can critically improve soil health..[13] However, research has proven that manure that has undergone biodigestion is a more effective fertilizer than raw, or fresh, manure.[14] Furthermore, the application of raw manure to soil can potentially contaminate agricultural products with hazardous pathogens. These pathogens are heat-sensitive, generally destroyed by temperatures of 36 degrees celsius or greater.[15] The active anaerobic bacterias of a biodigestion system are mesophilic, meaning that they thrive in temperatures of 15-47 degrees C,[16] although many show the ability to produce diverse and productive colonies in temperatures as low as 10 degrees celsius.[17] Biodigestion occurs optimally at 15-40 celsius.[1]This means that the effluent produced is pathogen free.

Dissemination of Different biodigester Models[edit | edit source]

Worldwide, the dissemination of different models of biodigestion systems has seen three general trends of biodigester design which are identified by their different countries of origin.[1]

China[edit | edit source]

From A CHINESE BIOGAS HANDBOOK[18] "Since the 1950s China has experimented with the production of biogas from agricultural wastes, a practice based upon an age-old Chinese tradition of composting human, animal and plant wastes to produce an organic fertilizer of high quality. The breakthrough came in 1975 when a process was developed to ferment the materials in an airtight and watertight container in order to produce methane gas." This "breakthrough" describes the innovation of the Chinese Fixed Dome biodigester, which has been reproduced in over 7 million systems around the world although the majority of these systems operate in China. The system is constructed of cement, thereby requiring skilled labor and an extensive installation time. In the field, the design has shown structural weakness in the low production of gas and the frequent occasion of gas leaks.[1]

India[edit | edit source]

The floating cover, or Indian, biodigester was designed to address the problem of gas leaks in the Chinese Fixed Dome. In this model, the gas storage mechanism consists of a floating cover, typically constructed of fiberglass, which rises in response to the generation of gas, therefore having a larger gas storage capacity. Although over 3 million have been constructed around the world, this system too is difficult to effectively demonstrate as the system consists of moving parts of high industrial cost (fiberglass).[1]

Taiwan[edit | edit source]

The Taiwanese, or "tubular plastic", design is the most economical of the 3 models discussed. As a result of high installation costs and difficulty in replacing parts, a continuous flow digester contained within a plastic bag was developed in order to achieve 1) greater weatherability 2) more efficient gas production 3) cheaper and more uniform manufacture and 4) a shorter installation time.[1]

Our project is based on this tubular plastic model for a biodigester. Specifically, we will be building a Biobolsa system, engineered by Sistema Biobolsa[19]

Mexico[edit | edit source]

- Current:

- Of the approximately 250 industrial biodigester projects that the Clean Development MechanismW (a mechanism of the Kyoto ProtocolW) has funded 200 of those are in Brazil and Mexico. Additionally, nearly 30% of all the 'waste gas recovery projects' are in Mexico making up about 110 projects of which the great majority are anaerobic digesters.[1]

- Future:

- Anaerobic digester systems may not be possible in some areas of Mexico due to water shortages.[20] However, in conjunction with the recently installed HSU Chiapas Rainwater Catchment system at Juan´s house, we foresee the functioning of our system without a considerable additional cost for water.

Criteria[edit | edit source]

| Criteria | Description | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Potential for Community Involvement | Must be a demonstration biodigester designed for educating the community. | 10 |

| Cost | Needs to have enough spending to support project but not so much to bankrupt the community | 9 |

| Level of Appropriateness | Project must be able to be incorporated in the setting and to the appeal of client | 9 |

| Durability | Needs to withstand use with no more than of $5-10 yearly maintenance. | 8 |

| Adherence to the Mission of IRRI | Meets IRRI's educational standards | 8 |

| Level of Energy Generation | Amount of Methane Produced | 7 |

| Level of Fertilizer Generation | Amount of Fertilizer Bi-product Produced | 7 |

Budget[edit | edit source]

| Materials | Unit Price (Pesos) | Quantity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Density Polypropylene Biobolsa (3000 liters) and Kit[21] | $8000 | 1 | $8000 |

| 4" PVC pipe | $35/m | 2 meters | $70 |

| 4" PVC wye fitting | $25 | 2 | $50 |

| 3/8" flexible hose (gas) | $7/meter | 55 meters | $385 |

| Cement | $115/bag | 2 | $230 |

| Chicken Wire | $22/meter | 1 | $22 |

| nails | $50 / kilo | found on site | $0 |

| 4" PVC pipe (for drainage system) | $46/meter | 5meters | $232 |

| Printing of Interpretive Signs | $2 | 6 | $12 |

| Laminating of interpretive signs | $16 | 12 | $192 |

| Glue (for PVC) | $12.5 | 1 | $12.5 |

| Corrugated Plastic Roofing Sheets | $360/sheet | 9 | $3240 |

| Post for roof (wooden) | $50/post | 6 | $300 |

| Buckets | $15/bucket | 2 | $30 |

| Cross Beams | $30/beam | 3 | $90 |

| Beams | $15/beam | 7 | $105 |

| Plastic Sheeting | $45/5 meters | 2 | $90 |

| bricks | found on site | 12-18 | $0 |

| natural gas stove | $210 | 1 | $210 |

| Total | $13270.5 | ||

Materials[edit | edit source]

-

Shovels are a must-have on every job site.

-

From these materials, we see the beginnings of our overflow system. Using a saw, a length of 4.5 meter PVC, and a 20 gallon bucket (which ironically held pig lard prior to its reappropriation as a Biol receptacle), we constructed a mouth on the rim of the bucket to accept the PVC from which will flow the Biol towards the second drainage bucket.

-

The pick necessarily served to break the high-clay content earth in the excavation of the trench.

-

We used plastic sheeting in order to build insulated housing for the biodigester.

-

High-density polypropylene which is the primary material in the actual Biobolsa.

-

Around the perimeter of the Biobolsa, we built a super adobe barrier which contained a reinforcing layer of brick tiles.

-

We used the costals to build our super adobe wall, first as earthen content and secondly as the structural basis itself.

The Site[edit | edit source]

We built our biodigester, the Sistema Biobolsa, at the house of Juan Hidalgo, on Calle Tapachula #55 in San Cristobal de las Casas. In San Cristobal, daytime temperatures average from 19° C. (66° F.) in winter and 23° C. (73° F.) in summer. Overnight lows average from 5° C. (41° F.) in winter and 13° C. (55° F.) in summer. < http://web.archive.org/web/20120518032001/http://innvista.com/culture/travel/mexico/sclc.htm > (July 11, 2010)

The coordinates of the house are : 16° 44' 27.46 N 92° 37' 39.78, at an elevation of 2154 m.

The house of Juan Hidalgo is a demo-house, in which the property itself seeks to be an example of eco-living. He has a 7 pigs, one rooster, a small garden and his home is made of super adobe and recycled materials. When we began our work on the location, the site for the biodigester showed many obstacles. There were two large mounds of pig manure, a rainwater cistern, and a variety of scrap wood.

-

Site for the biodigester

-

Site (roughly 7m x 3m) cleared and ready to begin digging.

-

The pigpen used to be given a layer of sawdust to facilitate cleaning but this practice had to be given up since the biodigester is unable to break down the lignin in the sawdust. (ref.)

-

Juan has three grown pigs, two females and one male. It's recommended that there be at least 6 pigs for there to be enough waste to put into the biodigester. Fortunately, he also has a future generation, four piglets. Once they're grown it will mean more Biol[22] and biogas produced more quickly.

Waste Chute[edit | edit source]

The waste chute, or Registro, is the structure in which the pig excrement drains from the Pigpen. Conveniently, Juan's pigpen had a small aperture in the side of the back wall which the piglets had priorly used to escape into the garden. We built our waste chute based on that aperture, using the opening as a space through which the excrement could be swept into the waste chute. The waste chute itself was constructed of compacted bricks and concrete. The most important feature of the waste chute is the 4" PVC pipe at the chute's far end. Through this pipe, the excrement travels by gravity into the Biobolsa.

-

Sand is sifted for concrete mixture.

-

Compacting bricks for base of waste chute.

-

Chicken wire is laid on top of crushed bricks for base.

-

Concrete and recycled brick is used to build the sides.

-

PVC pipe is cut to connect to Biobolsa.

-

Pipe is inserted and held with concrete.

-

Bricks are covered and sealed in concrete.

-

Waste chute is connected to the Biobolsa.

Digging the Biodigester Trench[edit | edit source]

The dimensions of the trench were determined by the dimensions of the Biobolsa. Based on the size 3 Biobolsa, we needed a trench with the following dimensions: (140 cm width * 460 cm length * 80 cm deep).

-

Breaking ground!

-

Here we marked the dimensions of the trench. Note the water collecting in the trench, a problem which we mitigated by building a rubble trench drainage system.

-

Alex of IRRI directs some hardworking student volunteers.

-

A tamp is used to level out the sides of the hole.

Rubble Trench Drain[edit | edit source]

We built our rubble trench drainage system in response to a large torrential rain which left our trench water logged. First, we dug a canal downhill from the biodigester site that terminated in a hole. We placed a PVC tube in the canal to accommodate drainage. Then we filled both the canal and the hole with large rocks. Lastly, we covered the system with dirt so that the ground would remain a viable workspace.

-

Here we see the terminal point of the drain, packed with large rocks.

-

PVC directs water to the end point.

-

Here students begin to recover the drainage system with dirt

-

In total, the system spanned 5 meters.

Prepping the Pigpen[edit | edit source]

The cleaning of the pigpen is necessary to ensure that no food waste enters the system upon installation. First, we collected all large solids in a series of 5 gallon buckets; this included both excrement and food waste. Care was taken to separate the two, so that the excrement present could be measured in the calculation of HRT. Then, while someone outside the pigpen gently sprayed the floor with water, the pigpen was swept clean of all food waste. After installing the waste chute, we noticed that some of the piglets had been taking advantage of the opening to escape from the Pigpen into the biodigester itself. Our final step in prepping the pigpen was the construction of a small bar to close off the entrance to the waste chute from the pigpen.

-

The pigpen is swept getting rid of any remaining sawdust.

-

Pig waste solids are then collected in buckets for measuring.

-

A final sweep is done to fully clean out pigpen and this was pushed through to the registro.

-

From the registro the dirty water drains into a bucket.

Roof[edit | edit source]

In order to maximize the durability of the Biobolsa, a roof is necessary to protect the system from the harshness of the elements. Additionally, as the anaerobic bacteria within the system require a mesophilic atmosphere to achieve optimal biodigestion, we used transparent corrugated plastic sheeting so that the roof system could serve as the basis for the development of a low tech greenhouse to house the Biobolsa.

-

Spacing for posts is measure and holes about one meter deep are dug.

-

The posts are placed in the holes and checked to be level.

-

The hole with the post in it is then filled with cement.

The rest of the roof was constructed by Juan.

Blanket & Costal Barrier[edit | edit source]

A geotextile blanket was placed in the trench in order to protect the Biobolsa from earthen weathering, including small rocks and pointed objects. To ensure that animals do not enter into the system, we built a barrier of costals, which are large 80 Liter sandbags that are often used in superadobe construction. As we eventually covered these costals in super adobe, the barrier served the dual function of insulating the system.

-

costals are moved from across the yard to the site and at an estimated 100+ pounds was no small feat!

-

To achieve a workable surface for the super adobe project to follow, Juan batters the costals to level the dirt clumps.

-

Here we see the beginnings of the costal wall. Underneath, the geotextile blanket is held firm in place.

Installation of Biobolsa[edit | edit source]

Installing the Biobolsa is a crucial process which requires care, precision and a strong understanding of the system's layout. For optimal functioning the Biobolsa must be perfectly centered in the trench with both the input and output pipes level. The biobolsa was placed directly on the geotextile blanket. We then filled the Biobolsa with water so as to displace the oxygen and initiate the anaerobic environment.

-

IRRI President and Biobolsa designer Alex glues PVC to the intake pipe

-

Alex explains the functioning of the gas release system

-

A view of the Biobolsa immediately before installation in the site

-

Here we have placed the Biobolsa in the trench, aligning its intake with the pigpen outlet

-

Juan and Alex work together to connect the Bolsa´s intake to the pigpen outlet

-

Alex connects the gas release system

-

Here we see the sulfur filter - our gas scrubber- of the gas release system

Biol exit & Overflow[edit | edit source]

We decided to build an overflow system for the Biol to create a system which could function without constant maintenance. Beneath the Biol exit, we dug a hole to accommodate a 20 liter bucket. We extended a canal 5 meters from that hole downhill and dug a second hole for the second, overflow bucket.

Insulating the System[edit | edit source]

To optimize internal temperatures within the Biobolsa, we built a greenhouse to house the Biobolsa. The roof itself is constructed of semi-transparent corrugated plastic sheets to trap heat from the sun. From the roof posts, we extended plastic sheets to create a greenhouse effect. By fastening the plastic sheeting to the costal barrier, the heat trapped by the plastic is conserved by the super adobe. To close the system, we built a super adobe wall of recycled bottles extending from the already existing cement wall of the pigpen.

Finishing Touches[edit | edit source]

As our system will function as a demonstration Biodigester, we wanted it to be as comprehensive as possible. To accomplish this, we finished our system by installing a series of informative signs to explain the various processes of our Biobolsa system. We created both Spanish and English language versions, and translated the key words of each sign into a regional language of San Cristobal to achieve maximum accessibility for visitors to the site. Here is a link to a word document of all the signs.

The Future of the System[edit | edit source]

As his pigs are not yet producing the desired amount of waste, Juan has mentioned that he is considering pursuing another supply of animal waste from a friend who raises cattle. With the proposed deposit of 3 kg daily of cattle manure, Juan will be able to boast the activity of anaerobic bacteria within his Sistema Biobolsa and reduce his HRT significantly. Another exciting plan includes using the waters harvested by the recently installed HSU Chiapas Rainwater Catchment system to plant a fall garden, which will be fertilized by Biol from the Biodigester.

Testing[edit | edit source]

Hydraulic Retention Time(HRT) = total liquid volume of system (L)/ daily input of water and effluent mixture (L/day)

This equation illustrates the amount of time that material (effluent) will reside within a biodigestion system before exiting as Biol,[22] however due to sedimentation not all material will have the same HRT.

In order to calculate the HRT, we measured the amount of waste produced by Juan´s pigs within a 24 hour period. Our HRT, based on three separate collections, is:

- Total volume of system = 3,000 liter (L)

- Daily input of water and effluent mixture = 2 liters of effluent/day + 12 liters of water/day = 14 L/day

- 1 month = 30.5 days

3,000 L / 14 L/day = 214.3 days, or 7 months

This value indicates that the system will require 7 months to complete biodigestion given a daily input of 2 liters of waste. As we have stated, the pigs in question are 3 mature pigs and 4 young piglets. As the four piglets grow, the daily input of waste is sure to follow. That said, the HRT can be expected to decrease with time.

Optimally, a company of pigs will produce 3 kg of waste per day. Given these conditions, we can calculate the rate of amortization.

Àmortization = (Cost of system) / ((Energy Produced/Year) + (Fertilizer/Year) + (Emissions Reduced/Year) + (Health Benefits) + (Quality of Life))

This equation illustrates the amount of time the Biobolsa will take to pay back its initial investment (not including the cost of infrastructure) as a result of energy produced (displacing the cost of other fuel sources), emissions reduction (which can be translated financially due to carbon market equivalencies), fertilizer produced (displacing the cost of fertilizer) along with the non quantifiable benefits of improved health and quality of life.

For the System Biobolsa at Juan´s house, we calculate:

$800 USD / (($300/year) + ($300/year) + ($40/year) + (Health Benefits) + (Quality of Life)) = 1.25 years*.

- This value does not include the value of health benefits or quality of life, which are indirect economic factors and challenging to quantify. However, it does indicate that once the system has reached optimal biodigestion, the system will pay back its initial investment after 1.25 years of functioning at capacity.

Video[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Eaton, A.B. (2009) "The Role of Small-Scale Biodigesters in the Engery, Health and Climate Change Baseline in Mexico" Masters Thesis, HSU Environmental Resource Engineering.

- ↑ http://www.irrimexico.org

- ↑ "38% of pig farms dispose of their wastewaters without any treatment directly into the nation's water bodies, which in turn has a severe impact on the environment" Victoria-Almeida, et al. "Sustainable Management of Effluent from Small Pigery Farms in Mexico" Instituo de Ingenieria, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Cd Universitaria 04510 D.F., Mexico.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mackie et al "Biological Identification and Biological Origin of Key Odor Components in Livestock Waste" J Anim Sci 1998. 76:1331-1342. http://web.archive.org/web/20060215040553/http://www.animal-science.org:80/cgi/reprint/76/5/1331

- ↑ Guan, Tat Yee and Holley, Richard A. "Pathogen Survival in Swine Manure Environments and Transmission of Human Enteric Illness" Dept. of Food Science, Faculty of Food and Agricultural Science, University of Manitoba, Winnepeg, Manitoba R3T 2NT Canada.

- ↑ To convert a known mass of methane to the universal CO2 equivalent (tonnes CO2e) global warming potential, multiply the methane mass by 21 (UNFCCC, 2008). Eaton, A.B. (2009) "The Role of Small-Scale Biodigesters in the Energy, Health and Climate Change Baseline in Mexico" Masters Thesis, HSU Environmental Resource Engineering.

- ↑ "One in four households use fuel wood for either all or part of their energy for cooking" [Masera O. 2005. From Cookstoves to Cooking Systems: The Integrated Program on Sustainable Household Energy Use in Mexico. Energy for Sustainable Development 9, no. 1: 25-36.]

- ↑ "Visible improvement in rural hygiene: Biogas contributes positively to rural health conditions. Biogas plants lower the incidence of respiratory diseases. Diseases like asthma, lung problems, and eye infections have considerably decreased in the same area when compared to the pre-biogas plant times. Biogas plants also kill pathogens like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid." Economy Watch (2010) (July 11, 2010)

- ↑ "One in four households use fuel wood for either all or part of their energy for cooking (Masera, 2005). The remaining energy needs throughout the country are met largely with Liquid Petroleum (LP) gas and electricity at a large economic burden for much of the low_income rural population."[Eaton, A.B. (2009) "The Role of Small-Scale Biodigesters in the Engery, Health and Climate Change Baseline in Mexico" Masters Thesis, HSU Environmental Resource Engineering.]

- ↑ "Before a biogas plant is built or a biogas program is implemented, a techno-economic assessment should be made. For this, two sets of cost-benefit analyses have to be carried out: · The macro-economic analysis (economic analysis) which compares the costs of a biogas program and the benefits for the country or the society. · The micro-economic analysis (financial analysis) which judges the profitability of a biogas unit from the point of view of the user. In judging the economic viability of biogas programs and units the objectives of each decision-maker are of importance. Biogas programs (macro-level) and biogas units (microlevel) can serve the following purposes: · the production of energy at low cost (mainly micro-level); · a crop increase in agriculture by the production of bio-fertilizer (micro-level); · the improvement of sanitation and hygiene (micro and macro level); · the conservation of tree and forest reserves and a reduction in soil erosion (mainly macro-level); · an improvement in the conditions of members of poorer levels of the population (mainly macro-level); · a saving in foreign exchange (macro-level); · provision of skills enhancement and employment for rural areas (macro-level)."[Habermehl Stefan, Kossmann Werner, Pönitz Uta, Biogas Digest:Volume III Biogas - Costs and Benefits and Biogas – Programme Implementation <www.gtz.co.za/de/dokumente/en-biogas-volume3.pdf>] (July 11, 2010)

- ↑ Taylor, John Poe, Removal of Hydrogen Sulfide from Biogas, August 2003.

- ↑ http://sistemabiobolsa.com/

- ↑ "Animal manure is a valuable fertilizer as well, conferring inputs to the soil over and above the simple chemical nutrients of N, P and K. As an input into the crop cultivation systems, manure continues to be the link between crop and animal production throughout the developing world." Rodríguez et al. "Integrated farming systems for efficient use of local resources" University of Tropical Agriculture-UTA, Finca Ecológica, College of Agriculture and Forestry,Thu Duc, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam

- ↑ "The biomass yield, and content of moisture and crude protein, of Chinese cabbage was highest when fertilized with biodigester effluent and lowest when fresh residual solids from manure were used." Thy, San and Buntha, Pheng "Evaluation of fertilizer of fresh solid manure, composted manure or biodigester effluent for growing Chinese cabbage (Brassica pekinensis)" Center for Livestock and Agriculture Development (UTA-Cambodia), POB 2423, Phnom Penh 3, Cambodia

- ↑ Ingham, et al. "Escherichia coli Contamination of Vegetables Grown in Soils Fertilized with Noncomposted Bovine Manure: Garden-Scale Studies" Department of Food Science,1 Hancock Agricultural Research Station,2 Lancaster Agricultural Research Station, 3 West Madison Agricultural Research Station, University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, Wisconsin (Received 5 March 2004/ Accepted 1 July 2004)-

- ↑ "Micro-organisms which live in temperatures of 40°C-80°C are "thermophiles" and those that live in 10°C-47°C are "mesophiles." Rose, A. H., and Wilkinson, J. F. (1979) "Advances in Microbial Physiology" Vol. 19, 1st Ed., New York, New York.

- ↑ Ahn, JH and Forster, CF (2002) The effect of temperature variations on the performance of mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic filters treating a simulated papermill wasterwater. Process Biochemistry, 37. pp. 589-594. ISSN 0032-9592

- ↑ Translated by Michael Cook, edited by: Ariane van Buren "A Chinese Biogas Handbook" Published by: Intermediate Technology Publications, Ltd. London WC2E 8HN United Kingdom 1979

- ↑ http://sistemabiobolsa.com/

- ↑ Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (2008) "Animal Waste Management Methane Emissions" Presentation prepared for Methane to Market. &amp;lt;http://www.methanetomarkets.org/documents/ag_cap_mexico.pdf&amp;gt;

- ↑ the IRRI Biobolsa system includes: the gas regulator system with sulfur filter, hose to connect to Biobolsa system and valve, a biogas reservoir bag and plastic net to suspend bag from roofing, a recycled PET plastic blanket to protect the Biobolsa, a repair kit for the Biobolsa and a use and maintenance manual for the whole system. <http://sistemabiobolsa.com/> Manual de Instalación.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Biol, a nitrogen rich liquid fertilizer, is the end product of the input effluent into the Biobolsa system. IRRI "Presentación_FIRA_lite.pfd"

![Juan has three grown pigs, two females and one male. It's recommended that there be at least 6 pigs for there to be enough waste to put into the biodigester. Fortunately, he also has a future generation, four piglets. Once they're grown it will mean more Biol[22] and biogas produced more quickly.](/w/images/thumb/6/6c/Juan%27s_Pigs.JPG/120px-Juan%27s_Pigs.JPG)