Electrostatic powder coating began in the early 1960's with the coating of pipes for increased durability and for insulating electrical components. In the 1960's electrostatic coating had already been used in many industries for finishing purposes with paints containing solvents.[1] With the introduction of powder coatings there was no need for solvents, therefore there are no volatile organic compounds evaporating into the atmosphere, or the health risk of inhaling them. Another environmental and economical advantage of powder coating is that the overspray can be collected and recycled back into the coating process. For this reason the material efficiency of powder coatings can come close to 100%. There has been a fast growth of the powder coating industry in the last couple of decades due to increased productivity and efficiency from switching from conventional solvent paints. Compared to traditional liquid coatings, powder coatings are more durable, impact resistance, corrosion resistance, and chemical resistant. Powder coatings fade less than liquid coatings and can be tailored for many different applications by changing color, gloss, coating thickness, and texture.[2] There are four main steps in the powder coating process: charging, transport, adhesion / deposition, and finally curing.[1] The basic principle behind powder coating is a charged particle, usually a polymer, is accelerated toward a grounded work piece and is adhered to the work piece by means of electrostatic attraction. The coated work piece is then cured at an elevated temperature transforming the powder coating into a smooth, and uniform polymer film.

Powder Coating Process[edit | edit source]

Powder Charging, Transport, and Deposition[edit | edit source]

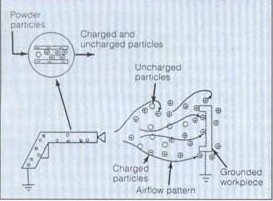

There are two commonly used methods of powder charging, corona charging and triboelectric charging. The method of charging used changes the transport characteristics of the powder, as well as the deposition of the powder onto the work piece.

Corona Charging[edit | edit source]

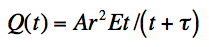

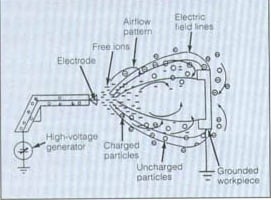

Corona charging of the powder is done by an electric spray gun. The powder is fed to the spray gun from storage containers using compressed air. At the tip of the spray gun there is a pointed corona electrode charged with a very high voltage. This high voltage creates an electric field between the corona and the grounded work piece. When the electric field in proximity of the electrode is 30 kV/cm or higher the air in this area will begin to breakdown and form a continuous release of free ions.[3] As the flow of powder particles passes by the free ions they attach to some of the particles and negatively charge them. The charged particles follow the electric field lines created by the electrode toward the work piece. Free ions that do not attach to a particle also follow the electric field lines to the work piece. Some particles do not get charged and are directed to the work piece by pneumatic forces. Equation 1 is the magnitude of the charge on a particle due to corona charging. Where Q = charge, A = particle composition constant, r = particle radius, E = electric field strength, t = time, tau = time constant.[4]

Deposition of Corona Charged Particles[edit | edit source]

The excess free ions created by the corona electrode have affects on the deposited particles. When using a corona gun the thickness of the layer of powder is limited due to a phenomenon called back ionization.[1]As the charged particles and ions build up on the work piece they begin to repel the incoming particles limiting the thickness of the powder and causing a pitted layer of powder. For this reason corona guns are mainly used for applying a thin layer of coating. Since the charged particles follow the electric field lines the uniformity of the coating is affected. The particles are more concentrated in the area closest to the gun and edges of the work piece.[3]

Triboelectric Charging[edit | edit source]

Triboelectric guns charge the powder particles using friction when the particle comes in contact with the walls of the gun and feed tube. The magnitude of the charge on a particle is proportional to the number of times it makes contact with the wall and the force with which it hits the wall. The most commonly used material for the walls of a triboelectric gun is Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or more commonly known as Teflon™. PTFE has shown to be the most efficient material for charging the powders by friction. Since the walls of the gun also attain a change during this process the gun and tube must be grounded to dissipate the charge built up in the PTFE. There is no electric field created by triboelectric charging since there is no electrode. With the absence of an electric field the charged particles are transported to the work piece by means of airflow only.[3]

Deposition of Triboelectric Charged Particles[edit | edit source]

Since triboelectric deposition does not have an electric field or excess free ions a thicker and more uniform coating can be achieve compared to a corona gun. The surface of the coating is smoother as well since there are no free ions. The only downfall of triboelectric charging gun is that the deposition rate is slower than corona charging guns. Using a triboelectric gun you lose productivity but the end result is better quality surface finish.[3]

Curing[edit | edit source]

After the power has been adhered to the work piece it has to be cured to the final product using heat. Temperatures for curing powders are around 140 - 220°C. At the elevated temperature the powder begins to flow and forms into a continuous film. The most commonly used method of curing the adhered powder coating on a metal substrate is by a convection oven. Convection heating uses fans to circulate hot air around an insulated room, and is the most popular method for curing metallic work pieces. It takes 15 – 30 minutes for a work piece to cure in a convection oven. An alternative to convection ovens is infrared radiation (IR) ovens. In IR ovens the powder coating and only a small volume of the work piece directly below the coating absorbs the IR radiation. In convection ovens a larger volume of the work piece is heated in order to each the curing temperature. For this reason the time it takes IR ovens to each the curing temperature is much less then a convection oven. An early limitation to powder coatings was that temperature sensitive materials such as woods and plastics could not be used due to the high temperatures of the ovens. A recent solution to this problem is using ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Specially formulated powders with photoinitiators are used that cure under UV radiation. Photoinitiators allow the UV radiation to crosslink the polymer coating at a low temperature.[5] The temperature sensitive part with UV curable powder is placed in a convention oven at 90°C for only 1-2 minutes to heat the powder. Then the part is placed under UV radiation and is cured in seconds.

Resins[edit | edit source]

Resins are the most important ingredients in the powder coating mixture, and determine the material properties of the finished product. There are many different types of powder coating resins to choose from each with varying properties. Most resins that are processed into powder coating applications can be categorized into two different types of polymers, thermosetting polymers and thermoplastic polymers.

Thermosetting Polymers[edit | edit source]

Thermosetting polymers make up 95%[2]of the resins used for power coating. When a thermosetting polymer is heated to a liquid and continues to be heated a chemical reaction occurs creating cross-linking of the polymer chains to form a material with different properties then before heating. The final solid film on the work piece when cooled is a tough, heat, and chemical resistant layer.[6] Examples of commonly used thermosetting polymers for power coatings are epoxy, epoxy – polyester hybrid, urethane polyester, polyester TGIC, and acrylic. Thermosetting polymers make up 95%[2]of the resins used for power coating.

Thermoplastics[edit | edit source]

Unlike thermosetting polymers, thermoplastics have the same properties after they have been melted and solidified onto the work piece. The surface finish of a thermoplastic is smoother than thermosetting polymer. Thermoplastics are commonly used for objects that will not be in harsh environments. Examples of commonly used thermoplastics are polyvinyl chloride, polyolefins, nylon, polyester, and polyvinlyidene fluoride.

Improving Energy Efficiency and Productivity[edit | edit source]

The step of the powder coating process that uses the most energy and takes the most time to complete is the curing process. Today a lot of companies use convection ovens to cure powder coatings. Convection ovens require lots of energy to raise the temperature on start up, to maintain a steady temperature and to operate the blower motors that circulate the air. There is substantial energy savings and productivity increase when an infrared oven is used instead of or in series with a convection oven. IR ovens are more efficient than convection ovens because the time to reach the curing temperature is shorter. IR ovens also save energy by having a very fast start up time compared to convection ovens. IR oven curing times are much faster, and they do not require blowers for circulation of heat. When using natural gas ovens the gas usage can decrease by 25%. Productivity increases by an increase in line speed, and a decrease in work piece cool down time since only a small volume of the piece is heated during the process. Productivity increases of 50% can be seen.[7]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bailey, A. G. (1998). The science and technology of electrostatic powder spraying, transport and coating. Journal of Electrostatics, 85-120.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 SpecialChem. (2009). Powder Coating Centre. Retrieved November 12, 2009, from http://www.specialchem4coatings.com/tc/powder-coatings/index.aspx?id=

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Knobbe, A. J. (n.d.). Tribo or Corona? Here's How to Decide. Retrieved November 12, 2009, from http://web.archive.org/web/20100117012348/http://sections.asme.org:80/cincinnati/Tribo.htm

- ↑ Knobbe, Alan J. "POWDER SPRAY GUNS." Nordson Corp., (2008): 242-54. Print.

- ↑ UV Curing Technical principle and mechanism. (n.d.). Ciba Specialty Chemicals. Retrieved December 2, 2009, from www.ciba.com/pf/docMDMS.asp?targetlibrary=CHBS_CE_MADS&docnumber=1628

- ↑ Barletta, M. (2008). Combined use of scratch tests and CLA profilometry to characterize polyester powder coatings. Surface; Coatings Technology, 1863-1878.

- ↑ "Infrared Heating Systems Curing Powder Coatings." Radiant Energy Systems, Inc. N.p., n.d. Web. 2 Dec. 2009. www.radiantenergy.com/TechnicalData/RadiantEnergySystems-PowderCoatingBrochure.pdf.