In the fall of 2005 Sarah Brunner and Shail Pec-Crouse, started a commercial pastured chicken operation in Arcata, California. The first four months see update of business were spent learning from other successful models, experimenting with different equipment, suffering through trials and tribulations, getting our hands bloody and planning improvements to our system. Throughout it all we have been guided by our core values of humane husbandry and sustainability.

We began with a very small flock of 175 birds and decided to try two different models of raising them on pasture to see which model worked the best for our situation. We compared the two models by looking at efficiency, loss to predators, land impact cost, fossil fuel use and mobility which strongly effects efficiency, land impact and fossil fuel use. After working with both models for a couple of months we came to the conclusion that the Chicken Tractor (CT) model is most appropriate for raising meat Chickens and the Hoop House (HH) model is more appropriate for raising laying hens. The CT is better for meat production because it is more cost effective and mobile and there is less predation. The CT is also important for pasturing laying hens for their first few months since there are less predator risks. The Hoop House is better for egg production because it accommodates nest boxes and roosts.

Our Models[edit | edit source]

Joel Salatin developed a pastured chicken meat production using "chicken tractors" that are 10' x 12', fully enclosed on one end and covered with netting on the other end.

How our chicken tractor differed from the model:

- Salatin's roofing and siding is made from aluminum. Our CT uses polycarbonate. Aluminum is much more durable and recyclable but is also extremely expensive. The price of aluminum has sky rocketed since the publication of Salatin's book. Aluminum is also much heavier and we already find the CT a little too heavy for easy moving.

- Salatin used plastic netting on the open end of his CTs. We used 1 inch chicken wire on the roof and quarter inch hardware cloth on the sides. Salatin recommends plastic netting because it is light weight. He also recommends a strip of hardware cloth on the bottom 6 inches of the north eastern quadrant to protect from raccoons reaching in and grabbing the birds. We decided to use the hardware cloth all the way around to be safe. We used wire instead of netting because I was unable to find appropriate netting, wire seemed more predator proof and I like to avoid non-recyclable or biodegradable materials.

- Salatin's design uses more cross braces to increase durability. We reduced the number of cross braces to reduce weight because the structure seemed to be sturdy enough with the bracing we installed. He also used a wire and turnbuckle to stop spreading on the bottom across the 10ft span. We used a 2x2 instead because we could attach a center support for the roof to it, it acted a perch and was less likely to trip the chickens.

- Salatin's design contained no roosts. We added 3 10ft roosts to give the birds a place to sleep off the ground. Chickens like to sleep on roosts and it helps keep them dry in the rainy season.

The design after which we modeled our hoop house:

- a free range operation in Marin County that used an identical hoop house

- Joel Salatin's "Eggmobile," which is a ramshackle coop on wheels, and the same electric fencing he uses.

How our hoop house differed from the model:

- we combined the hoop house with the electric fencing

- Our HH is on wheels, not skids, so that it can be moved by hand instead of by tractor. This allows it to be moved more often.

Hoop House Materials[edit | edit source]

- 10' x 18' and 8' tall

- plastic tarp roof is strapped over ribs of stainless steel pipe

- steel frame attached to new pressure treated 6x8 frame

- 1" square hardware cloth bottom

- five 10'long roost poles

- 30 nest boxes planned

- 2 hanging bucket feeders, one hanging 7 gallon waterer

- hoop house purchased on the internet, sold as a portable garage

- Cost: about $500 plus $500 shipping

- Capacity: 175 adult layers

- electric netting

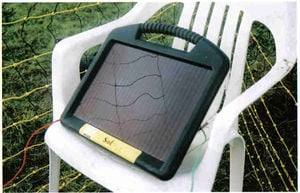

- Solar charger

- cost: $1600

Chicken Tractor Materials[edit | edit source]

- 10'x 12'x 2'

- Lumber is 95% recycled, 2%SFC certified 3% new and donated

- Hardware cloth

- chicken wire

- Recycled content corrugated plastic roofing

- Miscellaneous hardware (hinges, braces, etc.)

- Half of the tractor is enclosed in wire and the other half is enclosed in plastic roofing material to protect chickens from the weather and keep the chicken feed dry.

- The CT is moved by sliding a dolly under one end and pulling with a handle on the other end. We are in the process of getting a custom-made 4 foot wide dolly for easier mobility. We still need to install a handle on the dolly side of the CT to make it easier to get the dolly under the CT, and to make it possible to put the dolly on either side and pull the CT in either direction.

- During our first trial with the CT we simply watered the chickens with a 4 gallon waterer that sits on the ground. However for more efficient moving we purchased a Bell Drinker which hangs from the roof, and is gravity fed from a bucket that sits on top of the CT. We still need to work on ballasting the bell drinker to have it be fully functional.

- At first we fed the chicks in the CT with a bamboo trough, but it didn't hold enough food. We now use a bucket feeder, but we are still working on refining the feeding system and are considering larger bamboo feeders.

- Cost: $400

- Capacity: 40 adult layers or 85 juvenile meat chickens

Comparison of Hoop House to the Chicken Tractor[edit | edit source]

- Predators

- We lost more birds in the Hoop House to predators than from the Chicken Tractor. We suspected that the culprit was a weasel finding its way through or beneath the electric fence, although one night of predation may have been due to not hooking up the electric fencing properly. During the day the lack of netting above the pastured chickens makes them vulnerable to hawks, especially when they are small.

- Mobility

- The HH is very difficult to move by hand. It is extremely heavy and takes two people pushing or a truck to move.

- The CT was hard to move at first but has become much easier since using a custom dolly that helps it to pull along the ground. It is hard to move long distances though, which is problematic if it needs to be moved to a new pasture or close to an electric outlet for repairs.

- Land impact

- Our first HH model didn't have a floor and despite moving the HH every few days the ground inside got too high a concentration of feces. We installed a new wire floor and tarps beneath collect the feces so that the ground underneath the HH didn't get too much wear. However the land just outside the entrance still received excessive fecal deposits and grazing. The rest of the enclosure was grazed and defecated on fairly evenly and recovers (with new lush growth) within a week or two of the chickens being moved off.

- The CT causes more intense grazing but the birds are moved each day, preventing overgrazing. After moving the CT the grass recovers within a week or two. Feces are spread out except for the corner where they sleep, but this accumulation is small enough that the pasture absorbs it within two to three weeks.

- Efficiency

- The HH set up takes more time to move. The fencing must be taken down, the HH moved and the fencing put back up, but it accommodates many more birds--at least four times the number of layers and two times the number of meat birds.

- The CT is much quicker to move but can't accommodate laying hens easily because nest boxes add so much more weight to the CT.

- Fossil fuel use

- Currently the HH requires a truck to move with one person

- The CT is moved only by hand

- Cost

- The total cost of the HH was $1600, or approximately $10 per layer in the first year.

- The total cost of the CT was $400, also approximately $10 per layer or $5 per meat chicken in the first year.

- Accommodations

- The HH has a much larger area protected from rain in which nest boxes and roosts can be situated. Roosts are important for keeping the birds off the cold wet ground during the rainy season.

- The CT can be fitted with nest boxes and roosts but these items make it much too heavy for daily moving. Meat chickens are only raised in the summer so ground roosting is not as much of a concern.

Incorporating the Environment in Agriculture[edit | edit source]

There is a wealth of information available in books, movies and websites about the unhealthy, unsustainable and inhumane practices of industrial chicken farming. Rather than reproducing that work, we have collected below a list of ways in which a chicken tractor and a moving hoop house are a better way of rearing chickens for meat and eggs.

Chicken tractors and moving hoop houses:

- allow the chickens to be moved on to fresh pasture every day or two, which keeps the pasture from being overgrazed

- stop the build up of massive quantities of feces in the area used by chickens

- prevent health problems created by chickens standing in their own feces, a common problem in chicken operations that are not mobile

- spread feces out over the pasture so it is deposited in quantities that a healthy pasture can absorb and utilize. This stops burning of plant roots and nitrogen toxicity in the soil from excess feces, while fertilizing the pasture to encourage faster, lusher growth.

- provide chickens access to fresh plant matter, which is a natural part of a poultry diet. Fresh pasture makes for healthier birds, meat and eggs. Chickens with access to vegetation produce eggs and meat that contains less cholesterol and a lower percent of saturated fat. You can see this difference when you cook a conventional bird and a pasture raised bird side by side: the conventional bird's fat is white and hard at room temperature, indicating high saturated fat content. The pasture raised bird's fast is yellow and soft at room temperature, indicating more unsaturated fat content.

- reduce prepared feed consumption. Feed is primarily grains and soy beans which could be more efficiently fed to people than animals. Reducing feed also reduces fossil fuel use related to growing, harvesting, packaging and transporting feed.

- provide more room to move around than caged birds. This eliminates excessive pecking and cannibalism so we aren't compelled to debeak (cut off most of the upper beak and some of the lower beak) the birds.

- prevent a reduction in invertebrate diversity due to constant pressure from foraging birds. Pasture rotation confines the birds more, relieving pressure on the invertebrate community and ensuring there is always pasture that the birds do not have access to. This allows the invertebrate populations to reproduce and remain healthy.

-

overgrazing happens

-

overgrazing requires recovery

-

example of good pasture

-

example of recovering pasture

Other sustainable aspects of our operation[edit | edit source]

- Heritage breeds

- Conserving diversity in plant varieties and animal breeds is important for protecting against disease and maintaining the ability to raise products that do well in a particular climate. We started with a variety of breeds to see what worked best for us under our pasture and climate conditions. Two of the breeds, Production Red and Black Star, are industrial breeds. The other seven breeds are all heritage breeds. They include Minorca and Brown Leghorn, both of which are strictly egg layers, Araucana, Barred Rock, Australop and New Hampshire Red, all of which are dual purpose varieties.

Some unsustainable components of our farm and possible solutions[edit | edit source]

- Importation of grains and soy. Importing grains and soy from the Midwest for feed actually works at counter purposes with our overall goal, to grow a sustainable local protein.

- Grow grains ourselves or commission grains from a local farmer. Oats and wheat can both be grown in the Arcata climate and were at the turn of the last century. Growing grains ourselves would be a much larger investment of time and land and it would be difficult to produce without investments in machinery. Another downside is that the machinery would require fossil fuel, though we could run farm equipment on local recycled biodiesel. However, the local supply of biodiesel is limited and may not be able to support many farmers or many more residents. If we did grow our own grains we would be able to significantly reduce production waste that is common on grain-only farms: we would turn our chickens out onto the grain field after harvest to glean.

- Grow an alternative protein source since soy does not grow well here.

- Use fish by-products from local fishery as an alternative protein source. This may work well but fish isn't a natural component of the poultry diet. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals and toxins found in fish are also a source of concern.

- Imported chicks. Our first batch of chicks were hatched in a hatchery in Iowa. All hatcheries are out of state.

- Our goal is to eventually have a breeding flock to produce our own chicks. We need to research if this is economically viable since it requires that we either have hens that raise chicks for us or invest in an incubator. Mother hens are more appealing since they tend to reduce chick losses and make for happy chicks, but mother hens do not produce eggs for sale and while continuing to eat expensive feed.

- The hens would also probably need their own enclosure in which to raise chicks. If we use an incubator then the hens that produce the fertile eggs will continue laying eggs for the market. Fertile eggs also require roosters which eat feed and don't produce eggs, but they may help protect the flock from predators and increase the egg output of the hens.

- Farming away from home. Not living on the farm requires transportation to the farm which can be done by bike, but is often done with fossil fuel because of time constraints and hauling. The gas gets expensive but land lease is cheap. Not having the flock at home also increases mortality because we cant just run out the back door to check and see how high the creek is when it is raining or check to make sure the chicks are content with no drafts.

Primary Challenges:

- Feed costs are high because the cost of grain has been going up. Chickens tend to waste a lot of feed by scratching and flinging food out of the feeders. We haven't figured out how to stop this when they're chicks, but we did redesign our bucket feeders to have a deeper tray with a shallower depth of food, which has reduced food waste by 90%.

- Predators are a huge concern because a lot of money goes into each bird before she begins to lay eggs and money starts to come back. Chickens don't start laying until they are about 5 months old and only lay prolifically for about 2 years. This means we must feed them for a long time before we get a return. If we lose a layer after the first few months we lose a lot more than if we lose a meat bird which only costs money for about 2-3 months before butchering.

Update 2007 - $25,000 WINNERS[edit | edit source]

Shail Pec-Crouse and Sarah Brunner won $25,000 in the 2007 economic fuel competition with their mobile slaughter unit business plan. [1]

Update 2007/2008 - Change of usiness ownership[edit | edit source]

Since winning the business plan competition, Shail Pec-Crouse decided to leave Wild Chick Farm to pursue other endeavors. Sarah Brunner continues as the sole owner of the business. Sarah is now in the process of rebuilding the pastured poultry farm at a new location in the Arcata bottoms. The new farm will be utilizing 40 acres of lush perennial pasture grasses owned by a local grass-fed beef rancher. In collaboration with the rancher, Sarah will graze poultry in rotation with the beef cattle. This multi-species utilization of pasture land is a mutually beneficial relationship ecologically and economically. Following behind the cattle, the poultry enjoy the shorter grass left by the cattle and in return they help sanitize the fields of fly larvae that would otherwise infect the cows with parasites.

Stay posted for new updates on the progress of the new farm site or request to be added to the email list serve at wildchickfarm@gmail.com. Also, an official Wld Chick Farm website is in the works and is scheduled to be online this spring 2008. An announcement will go out to all emails on the list serve.

Bios[edit | edit source]

Sarah Brunner[edit | edit source]

Sarah grew up in the suburbs of Marin County, north of San Francisco. She moved to Arcata, CA to attend Humboldt State Univerity and study sustaniable development. Sarah's interests eventually sharpened to include all things agricultural related and after graduating HSU, working on several local farms, and managing a local farmer's market, she and her husband adopted their first flock of laying hens. Up until that point, the majority of Sarah's farming experience was with row vegetable crops. But she quickly grew found of the new batch of chickens and developed a strong appreciation for livestock...and hasn't looked back since.

In the fall of 2005 she invited Shail to join her in developing a chicken farm business.

Shail Pec-Crouse[edit | edit source]

I became a vegetarian at the age of 13 and vegan at the age of 19. My reasons for having a more restricted diet were mainly because of the environmental impacts of animal farming and the atrocious conditions that most food animals are raised in today.

As my understanding of the environmental impacts of an American diet became more sophisticated, I took a closer look at my diet and my reasons for not eating various foods. I started to buy only organic, then as much local food as possible.

Last fall my friend Sarah was tossing around the idea of a chicken farm, and I told her I would be interested in joining her as I have a passion for raising animals and was excited about growing my own food.