A bike blender is a pedal powered device which uses human power from bike pedalling to either power a blender directly through a mechanical connection or to generate electricity that will be used to power it.

- If you are searching for examples of DIY bike blenders made by Appropedia users, check out the projects section.

Basics

In physics, a calorie is the amount of heat required to raise one kilogram of water by one degree centigrade. In nutrition, a Calorie is 1000x the physics calorie, also known as a kilocalorie, however it is still referred to as a "calorie". When people eat food that contains Calories, they store these calories for later use, such as pedaling a bicycle or stationary bike blender. It is when they pedal a bike that they convert the stored calories into heat and work.[1]

A person pedaling a bicycle can accelerate to a speed and maintain it comfortably for a long period of time. This is referred to as "pacing." Beyond this point, a riders' velocity may reach high speeds, however the amount of energy required to keep up rapidly increased to a point where all energy from the rider is used up. This is because the amount of energy needed to keep the RPM's (rotations per minute) of the crankshaft up has exceeded the amount of energy the rider can actually produce and expend. These points vary according to each rider's skill and athletic condition.[2]

The bike itself works off of two gears or sprockets. One gear is under the rider's feet and is called the crank sprocket. This is where the pedals connect by way of the pedal arms. The other sprocket is attached to either the rear wheel (mobile bike) or the front wheel (stationary, exercise bike) and is referred to as either the rear sprocket or front sprocket. In general, the gear under the crank sprocket has more teeth (grooves for the chain to fit in) then the other sprocket. A gear ratio can be determined by dividing the amount of teeth the crank sprocket has by the number of teeth the rear or front sprocket has. For example, if the crank sprocket has 48 teeth and the front sprocket has 13 teeth, the gear ratio is 48/13 or 3.69. This means that for every rotation of the large gear, the small gear rotates 3.69 times.[3]

Types

Different types of bike blender designs are available for purchase and/or duplicating with fabricated parts.

Type 1 - Stationary Mechanical

This design is where the fly wheel of an exercise bike turns a skateboard wheel attached to a drive shaft. This drive shaft directly attaches to the fitting of the pitcher component of a blender. The blender is stabilized with counter like table top mounted in front of the bike. An advantage of this bike is that there are no electrical components involved! This design is purely mechanical which can also be a draw back because of the rarity of parts. Some parts for this design had to be specially designed and fabricated at a machine shop, which can be costly. Also, the parts used for this bike are not weather proof and are subject to rust. The whole design is also somewhat heavy, requiring at least two people to move.[4]

Type 2 - Stationary Electric

This design also modifies an exercise bike by connecting the flywheel to an electric generator with a fan belt. The generator operates at very low RPM's allowing the rider to power it with ease. An advantage with this generator is that any appliance working off of DC current can be operated not just a blender. A disadvantage is that the generator adds extra weight to the bike. Also, the wiring of the generator must be maintained to insure that the bike operates safely. This design is also not weatherproof. [5]

Type 3 - Mobile

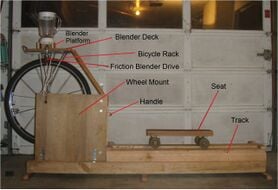

This design involves a stand that attaches to an ordinary bike in a way that elevates the rear wheel off the ground. Once the stand is in place and the rear wheel is elevated, a rider can power the blender by pedaling. An advantage to this design is that the stand and blender are separate from the bike, allowing any bike to be a possible bike blender. The disadvantage is the possible loss in efficiency by not having a stand and blender custom fit for a particular bike. [6]

Design Considerations

Maximum Power Output

According to ergometer tests conducted by Grosse-Lordemann and Muller, max power output for a 34 year old male who is not an athlete is about 110 watts at 80 rpm and 160 watts at 40 or 50 rpms sustained for 10 minutes.[7] A test conducted by students at Dartmouth College found that for an untrained average adult male, an output of 37 watts can be sustained for an indefinite period of time at 65 rpm, and an output of 71 watts can be sustained for 60 to 120 seconds at 90 rpm.[7][8] Another study found that peak average output of subjects was 142 watts for periods of more than 60 minutes.[7][9] In a study done on professional cyclists [7],[10] and on estimates made from UCI record holders[11], professional athletes can generate more than 400 watts for periods of at least an hour or more. In a related experiment, Renzo Sarti, an Italian sprinter, was able to produce 1,644 watts for 5 seconds.[12] Variations in power output are likely due to the ability of the test subject and testing conditions, such as the equipment, quality of bike fit, and riding posture.

Preferred Cadence

Cadence on a bicycle refers to the number of rotations per minute of the crank. Cadence is related to power output because power output is a function of force applied to the pedals and cadence, this relationship being: Power (watts) = Pedaling speed (m/sec) * Thrust force (newtons). Cadence can't be directly related to power output, as different crank arm lengths will yield different pedaling speeds for a given rpm. According to a study done on trained bicycle racers by Coast, Cox, and Welch, optimal efficient pedal rate over a 20 to 30 minute period is between 60 and 80 rpm. At 80 rpm, perceived exertion and lactate levels were lowest.[12] [13]

Saddle or Seat

The seat can be adjusted by loosening a clamp bolt with a crescent wrench. There is also another bolt for adjusting the tilt of the seat. These two points may become weak with more riders of varying sizes and should be inspected and replaced when necessary. It is suggested that at least 2 ½ inches of the seat post are should remain in the seat tube at all times. For taller riders, it is possible that this recommendation will not be followed and possible breakage of the seat or seat post could result. This recommendation should always be followed to prevent this.[14]

Related projects

References

"SDG03 Good health and well being" is not in the list (SDG01 No poverty, SDG02 Zero hunger, SDG03 Good health and well-being, SDG04 Quality education, SDG05 Gender equality, SDG06 Clean water and sanitation, SDG07 Affordable and clean energy, SDG08 Decent work and economic growth, SDG09 Industry innovation and infrastructure, SDG10 Reduced inequalities, ...) of allowed values for the "SDG" property.

- ↑ Krausz, John, Vera van der Reis Krausz, and Paul Harris. The Bicycling book: transportation, recreation, sport. New York: Dial Press, 1982.

- ↑ "Bicycle efficiency and power -- or, why bikes have gears." User Home Pages. http://users.frii.com/katana/biketext.html (accessed February 15, 2011).

- ↑ bicycling fitness program: a complete guide to equipment and exercise. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985.

- ↑ "The Pedal Powered Mechanical Blender." Pedal Powered Innovations by Bart Orlando. friends.ccathsu.com/bart/pedalpower/inventions/frames_final_htm..htm (accessed February 15, 2011).

- ↑ "The Pedal Powered Electric Blender." Pedal Powered Innovations by Bart Orlando. http://friends.ccathsu.com/bart/pedalpower/inventions/frames_final_htm..htm (accessed February 15, 2011).

- ↑ "Bike Blenders - Features | Rock the Bike." Rock the Bike. http://www.rockthebike.com/node/325/features (accessed February 15, 2011).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Whitt, Frank Rowland, and David Gordon Wilson. Bicycling Science. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1982. 42-52.

- ↑ Report on the Energy-Storage Bicycle, Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., 1962.

- ↑ D. R. Wilkie, Man as an aero-engine, Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society 64 (1960): 477-481.

- ↑ T. Nonweiler, The work production of man: Studies on racing cyclists, Procedings of the Physiological Society, 11 January 1958. 8-9.

- ↑ Perry, David. "Bike Cult Book: Online Resource: World Hour Records." BikeCult.com. N.p., 28 July 2005. Web. 15 Feb. 2011. < http://www.bikecult.com/bikecultbook/sports_recordsHour.html>

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Abbott, Allan V., and David Gordon Wilson. Human-Powered Vehicles. Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics Publishers, 1995. 34-37.

- ↑ Coast, J.R., Cox, R.H., and Welch, H.G. (1986). Optimal pedaling rate in prolonged bouts of cycle ergometry. Medicine and Science of Sports and Exercise, 18(2), 225-230.

- ↑ Call, Frances, and Merle E. Dowd. The practical book of bicycling. New, rev. ed. New York: Dutton, 1981.