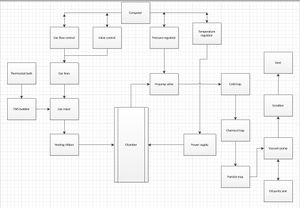

The primary method for deposition of InGaN is Metal-organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD), a form of chemical vapor deposition (CVD), pictorially discribed in Figure 1. This method creates layers of material with a thickness ranging between 15-60nm. The epitaxial layer is formed by pyrolysis of chemicals such as trimethylgallium (TMG), triethylgallium (TEG), and trimethylindium (TMI)[2] on GaN[3] or sapphire substrates.[4] Using sapphire substrates can cause complications in determining index of refraction through spectroscopic ellipsometry due to its transparency. In these situations GaN substrates are preferable.[5]

InGaN can be difficult to produce due to the fact that high Indium percent InGaN decomposes around 700 C, but the popularly implemented methods of production take place at over 1000 C.[6]

These pyrophoic metalorganic precursors are thermally decomposed in a tightly controlled steel chamber, releasing volatile radicals as exhaust, which will be converted to less hazardous oxides.[7]

There is no experimental data available yet on InGaN but GaAs has similar qualities. When metal-organic chemical vapor deposition is used only 2-10% of hydrides are actually deposited on the photovoltaic panels. InGaN is estimated to have a 20-50% material utilization rate, based on GaAs.[8]

This means that over 80% of the precursor will remain unreacted. In the form of hot, toxic gases, these chemicals must be trapped and neutralized for safe handling.

As shown in Figure 1, the first step of this process usually involves a cold trap. Cooled with liquid nitrogen or a slurry of dry ice and acetone, the hot gas may condense into a solid substrate unto the inner wall of the trap. After this, corrosive materials are caught in a chemical trap consisting of charcoal and other chemicals. These chemicals may include sodium hydroxide to absorb hydrogen chlorides and calcium hydroxide to neutralize hydrogen flourides. Large particles in the form of soot are usually absorbed by oil located in the bottom of the ensuing particle trap. Finally, the remaining gas is bublled through a sodium hydroxide solution (2-6% NaOH), in which all remaining acidity is neutralized to a safe level (about 95% efficient). The remaining gas is released into the atmosphere to prevent unsafe pressure build up.[1]

Some other methods of deposition are hybrid vapor phase epitaxy, molecular beam epitaxy, and ion assisted deposition.

Equation 1:

Equation 2:

Equation 3: mass/unit area

InGaN solar cells are normally produced in 1x1, 3x3 or 5x5 mm2 segments with typical thicknesses of 200 nm .[9] The process used for estimating the amount of material per unit area of a single cell is outlined with equations 1 through 3. Using equation 1, where a,b and c are the edge lengths, the volume of a 1 mm2, 200 nm thick InGaN cell was found, after converting to meters, to be 2*10-19 m3. The density of an InGaN layer was calculated using equation 2, where P is the elemental density and X is the fraction present. Given the densities of In(7.31 g/cm3[10]) and Ga(6.15 g/cm3[11]), a cell with a composition of In.05Ga.95N has a density of 6.2 g/cm3. Converting units and multiplying the density by the volume (equation 3) gives the mass per unit area of an average cell as 1.24 g/m2.

Efficiency[edit | edit source]

The sun provides the surface of the earth with light having energy of approximately 1000 W/m2. Reported InGaN power densities range from 20-29.5 W/m2.[12] This means that these cells are currently taking power from the sun at efficiencies of 2-3%. The fill factor is another way of quantifying the efficiency of a solar cell and is determined by comparing the max power generated by the cell to the open circuit voltage and short circuit current. Production grade solar cells have fill factors of 70-85%.[13] Experimental InGaN cells have shown fill factors up to 60%.[14] Based on earlier stated data, InGaN cells have material energy data of 25-36 g/W. Depending on In and Ga content, an array will require 25-36 grams of material to produce one watt of power.

Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) has committed studies for the effects of polarization-induced fields and spillover effects in indium gallium nitride (InGaN) LEDs using m-plane gallium nitride. The reasoning for these studies was to grasp a better understanding for the typical efficiency drop often occurring at current densities higher than 50A/cm2.[15]

One explanation was an Auger-like process is interrupting the electron-hole recombination sequence which produces photons. Inevitably distinguishing the LED light as you increase the current. However Hadis Morkoç (one of the leaders of the VCU group) points out that this effect should mainly affect blue–green LEDs with wavelengths around 500nm, corresponding to photon energies of about 2.5eV. This is due mainly to that fact that an enhanced Auger coefficient seems to occur when the InGaN semiconductor reaches this particular band gap, as well as the groups findings that the emission wavelengths from the VCU devices were around 400nm (3eV), which is well above the theoretical peak in Auger enhancement.

Purity[edit | edit source]

There are a few ways to obtain semiconductor or solar grade InGaN. Gas purification systems can be used with MOCVD to increase purity in semiconductors. Gases used can be H2, Ar, or NH3. This is an efficient method of purification.[16]

Zone remelting (zone refining) is another method of semiconductor purification that is implemented on InGaN. This process involves passing a tube of semiconductor material through heating coils so the impurities are contained to the molten parts which are swept away. This usually takes 2-5 passes. Zone melting can reduce impurities to as little as.1 ppb.[17]

A study preformed by Piner et. al. using secondary ion mass spectrometry showed that the concentration of H, C, and O impurities in InGaN was directly related to the hydrogen and NH3 gas flow rate during MOCVD. C and O impurities decreased by two orders of magnitude, H by one order, when the Hydrogen flow rate was increased from 0 to 100 sccm. Increasing the NH3 rate from 1 to 5 slm saw a decrease in C impurity concentration, but an increase in O and H concentration. An increase in InN percent is shown to have an increase in impurities.[18]

Characterization[edit | edit source]

The In fraction of InxGa1-x can be determined through Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy. Thickness of InGaN layers can be determined with cross-sectional field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM).[5]Photoluminescence is one method used to characterize material quality, unintentional doping level, and impurity energy level in InGaN.[19] PL can also be used to determine the radiative efficiency and spatial uniformity of InGaN quantum wells. X-ray diffraction is used to quantify alloy composition and periodicity in InGaN. Strain on thin film samples must be accounted for when calculating this. The degree of relaxation can be determined by asymmetric reciprocal space mapping.[20]

Recycling Facility[edit | edit source]

The "InGaN solar cell manufacturing facility" is the first facility to successfully produce and maintain the epitaxial structures for the InGaN semiconductor. We operate using MOCVD (Metal Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition) epitaxial reactors to produce between 2"-8" GaAs based epitaxial wafers and our main applications are LED's and solar cells.

We operate under a fabrication line housed in a 10,000 square foot, class 100/1000 clean room, in which we incorporate testing procedures such as: Wet and dry etching, metallization, dielectric decomposition, RPT, dicing, die & wire bonding, encapsulation and final testing.

Some of the equipment and In-house instrumentation we use is listed below.

- CMP (Chemical mechanical polishing)

- Wafer Probing Machines

- Polish Grinders

- Wafer Probing Machines

- Wafer Dicing Machines

- Double crystal X-Ray diffraction

- Semiconductor parameter analysis

- Wet oxide confinement growth station

- Heat uniform hot plate

Some of the common electrical issues we tend to find during our processes are particle contamination, equipment problems and electro static discharge (ESD). The main cause of these issues is failing to control the static charge of the semiconductor. This is normally due to external particles entering the clean room and bonding with the product. Causing defects in the semiconductor production in much the same way that dust on a photographic negative or printpaper causes a visual defect.[21]

Uses for Recovered Indium and Gallium[edit | edit source]

The two primary elements to be recycled in InGaN are the Indium and Gallium components and since the manufacturing efficiency for Indium is only 15% efficient, about 50% of the InGaN waste is disposed of and the other 50% is treated off-site for recovery of the gallium fraction. Based off studies for GaAs and since InGaN is not at this time considered hazardous waste the disposed material generally gets placed in 55-gallon barrels and disposed in land fills, while the recovered waste gets sent to the only existing U.S. recycler to be further processed.[22] Recycled Indium and Gallium will be mainly used in production of new solar cells and LEDs. However, there are multiple other uses for these elements and, depending upon the economics of certain applications, recovered In and Ga could be directed toward products that are most profitable. Some of the alternate uses are shown below.

Gallium[11]

- Substrate in microchips and other circuit applications

- Gallium alloys are used in high quality mirrors

- High temperature thermometers - Ga in Quartz thermometers measure up to 1000 Celcius[23]

- Ga salts used in medical imaging

- Component in alloys with low melting points (Ga Tm~30 C)

Indium[10]

- Used as doping agent in transistors and other electrical devices

- High quality mirrors

Waste Recycling Proposal[edit | edit source]

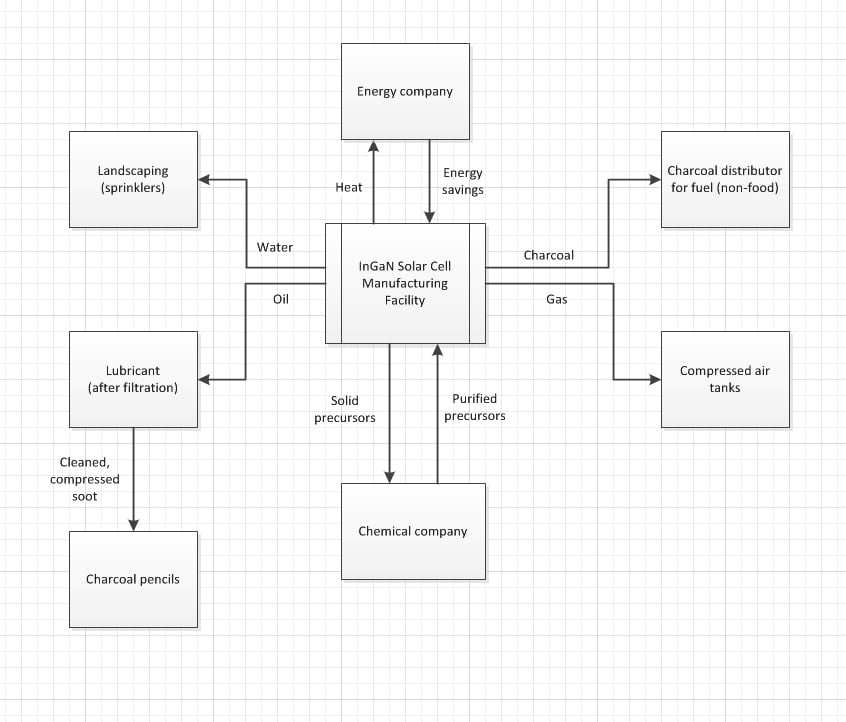

After examining the MOCVD process (which is a derivation of CVD), it can be deduced that there are many types of wastes produced. These wastes include a mixture of unreacted solid precursors, charcoal, oil contaminated with soot, water, heat, and gases with minor levels of toxic elements.[1]Below is a schematic of a proposed recycling route:

Using the power density listed above as 20-29.5 W/m2, demensional analysis will yield a required area of 34,000-50,000 m2 to produce a power output of 1MW/m2. In the Process section above, it was found that 1.24 g of InGaN is required to produce a square meter layer. Assuming the lower power output value of 20 W/m2, a total of 775 g/MW, or 1.29 kW/g, is calculated. To power a 60-W light bulb, this converts to about 215 kW-hr/g of power.

Taking the mole fractions of the formula used for the previous analysis (In.05Ga.95N) and MOCVD effiency of 20%, the following table is produced per MW produced:

| Substance | Net Required Amount (g) | Gross Amount (g) | Precursor | % Precursor Comp. | Gross Precursor Amount (g) | Price ($[24]) | Wasted Precursor Amount (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In | 19.375 | 96.875 | TMI | 71.79 | 135 | 17,145 | 108 |

| Ga | 368.125 | 1840.625 | TMG | 60.72 | 3032 | 385,064 | 2,425 |

| N | 387.5 | 1937.5 | N2 | 100 | 1937.5 | 4/L | 1,550 |

*Note: There was no pricing information available for TMI, but since the cost of TMG=TEG, the cost of TMI was assumed equal.

*Gross precursor amounts and wasted precursor amounts were rounded for simpler review.

*Nitrogen is a gas.

If 95% of 80% of this initial material is assumed recoverable, then 76% of the above material is available as waste. Roughly estimating the collection efficiency of each trap as 30%, 60%, 40%, and 95% for cold, chemical, particle, and bubbling, respectively, yields total corresponding recovering efficiencies of about 30%, 42%, 11.2%, and 15.96%, leaving 0.84% as additional gaseous waste.

Taking these results, a total of about 883.5 g of InGaN (in the form of mixed precursors) can be recovered and sent to a chemical supplier where it can be purified and shipped back. Using the previously discussed value of about 775g/MW and assuming 100% material utilization, this is about 1.14 MW of power, or 19,000 kW-h/g in reference to a 60-W light bulb.

Since the recycling of wastes in the form of water, heat, charcoal, gas, and oil/soot does not require intense purification, the processes to do so should be fairly inexpensive, relatively speaking. However, since MOCVD relies on the purity of the precursor chemicals, the purification of the solid waste calculated about will be much more costly. However, since the chemicals are assumed to be introduced to the chamber at the same time and were collected immediately after deposition, minimal purification and re-vaporization of the cooled solids may prove sufficient.

Safety[edit | edit source]

Gallium and Indium are both pyrophoric elements, reacting violently to oxygen and water. Both elements are known to spontaneously combust in order to produce less volitale oxides.[1]Although gallium itself is not known to be toxic, indium and nitric acid, which may be used for cleaning substrates before undergoing MOCVD, have very strict safety limits. These limits are listed below:

| Substance | TLV-TWA (ppm) | STEL (ppm) | IDLH (ppm) | Hazerdous Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In | 0.1 mg/m3 | n/a | n/a | pulmonary, bone, GI |

| Nitric Acid | 2 mg/m3 | 4 | 2.4 | irritant, corrosive |

The Theshold Limit Value- Time weighted Average as well as the Short-time Exposure Level are both established by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). IDLH, or Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health level, is established by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Helath (NIOSH).[5]

To reduce the toxicity of unused chemicals during MOCVD, exhaust abadement systems are largely based on charcoal absorption of unreacted hydrides and metalorganics. The charcoal is fed with oxygen or water to promote oxidation in order to produce less toxic oxides. Newer MOCVD systems also use wet scrubbing with water or sulfuric acid (pH= 3-5) or combustion to further netralize toxicity.[1]

Here are the Material Safety Data Sheets for some compounds used in MOCVD as well as other chemicals mentioned above:

Trimethylgallium

Triethylgallium

Trimethylindium

Nitric Acid

Sulfuric Acid

Gallium Nitride

Sodium Hydroxide (0.1 M)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Yan, Xiu-Tian, Yongdong Xu. Chemical Vapor Deposition. Engineering Materials and Processes 2010

- ↑ Shenai-Khatkhate, Deodatta. Environment, health and safety issues for sources used in MOPVE growth of compound semiconductors

- ↑ Jani, Omkar. Design and Characterization of GaN/InGaN Solar Cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 132117 (2007); doi: 10.1063/1.2793180

- ↑ Keating et al. Effects of Substrate Temperature on Indium Gallium Nitride Nanocolumn Crystal Growth. Cryst. Growth Des., 2011, 11 (2), pp 565–568

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sanford et al. [Refractive index and birefringence of InxGa1–xN films grown by MOCVD]. phys. stat. sol. (c) 2, No. 7, 2783–2786 (2005)

- ↑ Patel et al. Characterization of InGaN Based Photovoltaic Devices.

- ↑ Shenai-Khatkhate, Deodatta. Environment, health and safety issues for sources used in MOPVE growth of compound semiconductors. Journal of Crystal Growth. Vol 272. Issues 1-4. 10 December 2004, Pages 816-821

- ↑ Fthenakis, V.M. Overview of Potential Hazards.Practical Handbook of Photovoltaics. 2003.

- ↑ Jani et al. Design and Characterization of GaN/InGaN Solar Cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 132117 (2007)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 [Indium Properties]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gallium Properties.

- ↑ Cooke, M., Texas Tech 'significantly' improves InGaN solar cell performance. Semiconductor Today. August 24, 2010.

- ↑ Green et al. Solar Cell efficiency tables (version 37). Prog. Photovolt: Res. Appl; 2011; 19:84-92

- ↑ Dahal, R. et al. InGaN/GaN multiple quantum well solar cells with long operating wavelengths. Applied Physics Letters 94. 2009

- ↑ Cooke, M. InGaN LED spillover and efficiency droop. Semiconductor Today. Dec 1, 2009.

- ↑ Heuken, M. INDOT (MOCVD technology for production of indium nitride based nanophotonic devices).

- ↑ Roussopoulos, G.S, Rubin, P.A. A Thermal Analysis of Horizontal Zone Refining of Indium Antimonide.

- ↑ Piner et al. Impurity dependence on hydrogen and ammonia flow rates in InGaN bulk films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 71, 2023 (1997).

- ↑ Li, Shunfeng. Growth and Characterization of Cubic InGaN and InGaN/GaN Quantum Wells

- ↑ Dupuis et al. Optical and Structural Characterization of InGaN Quantum-Well Heterostructures Grown by Metalorganic Chemical Vapor Deposition.

- ↑ Steinman, Arnold. Preventing Electrostatic Problems in Semiconductor Manufacturing. Compliance Engineering, 2004

- ↑ Swartzbaugh, Joseph. REDUCTION OF ARSENIC WASTES IN THE SEMICONDUCTOR INDUSTRY

- ↑ Boyer, S. Gallium-in-Quartz Thermometer Graded to 1000 C. Ind. Eng. Chem., 1925, 17 (12), pp 1252–1253

- ↑ Sigma Aldrich Company Page