Traumatic injury is one of the top 10 leading causes of death and disability in the world. Not only does traumatic injury account for 16% of the global burden of disease, the 5.8 million deaths per year from traumatic injury accounts for almost 10% of the global annual mortality.[1][2] It is a major cause of death for people younger than 45 years old, and the main cause of traumatic injury is accidents. In the US, trauma is the 4th leading cause of death for all ages.[3][4]

Why is this important?[edit | edit source]

Injuries from road traffic accidents are another source of high morbidity and mortality, as well as financial impact. The estimated annual cost of road injuries is $518 billion globally and $65 billion in low-income countries.[4][5] Road traffic injuries cost 1-2% of the gross national product, which is more than the total development aid received by these countries. Multi-system trauma victims have a 50-58% rate of returning to work in 2 years after injury, contributing to an economic burden in their countries.[6][7]

The impact of road traffic injuries is particularly momentous in low- and middle-income countries. In these countries, traffic-related injuries comprise 30-86% of all trauma admissions. Road traffic accidents injure and kill 50 million and 1.3 million people, respectively, annually around the world.[8] This means ~3200 deaths daily due to road traffic accidents, and 90% of these deaths occur in low- or middle-income countries. The mortality rate for serious injuries, occurring both pre-hospital and in-hospital, ranges from 35% in high-income countries, to 55% in low- and middle-income countries, and up to 63% in low-income countries. For moderate injuries taken to a rural hospital in a low-income country, there is a 6-fold increased risk of death compared to a high-income country (36% vs 6%).[2]

The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol is a systematic approach to recognizing, triaging, and managing life-threatening traumatic injuries. It was developed by trauma care providers in the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma and has been widely adopted and implemented around the world.[9] One of the core components of this systematic approach to the traumatically injured patient is the assessment and control of life-threatening problems with circulation. For trauma patients, this almost always implies bleeding. After a quick assessment of the patient’s airway and breathing, providers assess the patient’s circulation oftentimes by blood pressure measurement or pulse exam, as well as evaluating for major sources of bleeding.

Death by Blood Loss[edit | edit source]

Hemorrhage is responsible for 30-40% of all trauma mortality, and on the battlefield, this increases significantly up to 90% of deaths.[10] Exsanguination is the primary cause of death for patients who are either dead upon EMS arrival or within the first hour of EMS arrival, with 33-56% of hemorrhage-related deaths occurring during the prehospital period. Bleeding accounts for 50% of hospital deaths within 24 hours, as well as 80% of operating room deaths after major trauma.[11]

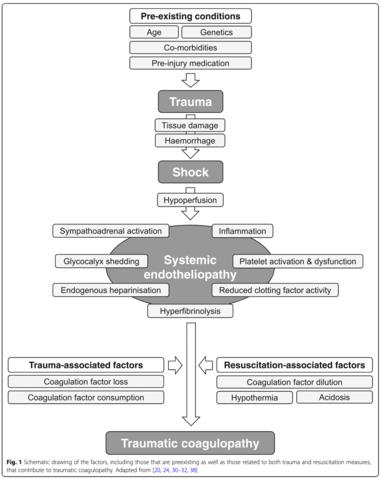

One-third of bleeding trauma patients show signs of coagulopathy on admission. These patients are at greater risk for multisystem organ failure and death than patients with other diseases or similar injury patterns in the absence of coagulopathy. Early acute coagulopathy associated with traumatic injury has recently been defined as a multifactor condition, based on hemorrhagic shock, thrombomodulin upregulation related to tissue damage, thrombin-thrombomodulin complex generation, and activation of anticoagulation and fibrinolytic pathways.[12] Other factors affecting the severity of clotting disorders include acidemia, hypothermia, dilution, hypoperfusion, and coagulation factor consumption. Additionally, coagulation dysfunction is further influenced by trauma-related factors (e.g. traumatic brain injury) and patient-related factors (e.g. age, comorbidities, genetic conditions, medications).

Multiple variables are associated with death by exsanguination, including the type of injury, location of injury, and presence of arterial hemorrhage. Classifications of hemorrhagic shock (Table 1) can be used for prompt diagnosis and management of blood loss.[13]

| Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood loss (mL) | <750 | 750-1500 | 1500-2000 | >2000 |

| Blood loss (%) | 15% | 15-30% | 30-40% | 40% |

| Pulse (bpm) | <100 | >100 | >120 | >140 |

| Blood pressure | Normal | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 14-20 | 20-30 | 30-35 | 35-40 |

| Urine output (mL/hr) | >30 | 20-30 | 5-15 | Negligible |

| Mental status | Normal | Anxious | Confused | Lethargi |

Bleeding patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms. Oftentimes they are pale, cool, and report dizziness, sweatiness, and difficulty breathing. The pulse can be extremely fast or weak, thready, and difficult to palpate. High clinical suspicion for bleeding is essential in assessing trauma patients.

There are also different sources of bleeding (Table 2). External bleeding is visible on the body surface–this is the foundation of our Simulator model. In addition, trauma can cause damage to internal structures leading to internal bleeding, which is typically not visible to a bystander and can be equally or more life-threatening.

| Arterial | Venous | Capillary |

|---|---|---|

- Bright red blood in a pulsating fashion

|

- Darker red blood, non-pulsating

|

- Most common and with the lowest life-threatening risk

|

While traumatic bleeding occurs at the site of injury on the body, there are certain locations where severe blood loss is life-threatening–the chest, abdomen, pelvis or retroperitoneum, and notably for our CrashSavers Trauma course, external wounds and into the long extremities. While more invasive approaches are warranted to control bleeding within the chest, abdomen, or pelvis, the application of adequate hemorrhage control techniques for compression of external and extremity injuries can stop or temporize life-threatening bleeding until definitive care can be performed.

Large, important blood vessels of the neck, arms, groins, and legs can cause significant blood loss very quickly if injured and if left uncontrolled. A review of the anatomy of upper and lower extremity vasculature can be found at the links provided below.

| Neck anatomy | https://teachmeanatomy.info/neck/ |

|---|---|

| Neck vasculature | https://teachmeanatomy.info/neck/vessels/ |

| Upper limb vasculature | https://teachmeanatomy.info/upper-limb/vessels/ |

| Lower limb vasculature | https://teachmeanatomy.info/lower-limb/vessels/ |

Hemorrhagic shock can lead to hemodynamic instability, followed by decreased tissue perfusion, organ damage, and ultimately, death. Two main goals to avoid this include: 1) stopping the bleeding, and 2) restoring circulatory volume. To facilitate this, first responders have to be trained to triage and act in a timely manner. The hemorrhage control techniques taught in our CrashSavers Trauma course can help providers prevent morbidity and mortality from external and extremity traumatic injuries.

Attention to Prevention[edit | edit source]

Importantly, uncontrolled post-traumatic bleeding with hemorrhagic shock is the main preventable cause of death worldwide.[14] Almost a third of all trauma deaths are considered preventable, and uncontrolled bleeding accounts for 64% of these deaths.[15] Providing early, effective triage and control of external bleeding significantly increases the chances of victims’ survival, thus, demonstrating the impact and need for well-trained first responders.[16][17]

In the military, protocols to manage trauma and hemorrhage in extreme conditions are well-established with the use of evidence-based protocols. Ample studies and expert opinion have shown that bleeding is the leading cause of preventable death for penetrating trauma. As a result, the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) program has recommended the early use of tourniquets and pressure dressings for hemorrhage control, leading to a significant reduction in the number of preventable deaths.[18]

Additionally, with a rise in active shootings since 2012, the Hartford Consensus took place in the US in 2015 and was led by the American College of Surgeons, using supporting evidence from the US Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the US Fire Administration. The directive included recommendations for national preparedness, planning, prevention, and protection of communities. The Consensus highlighted the importance of incorporating tourniquets and hemostatic agents as a part of hemorrhage control by first responders and the general population.[19]

The acronym, “THREAT”, was created to represent the necessary response to mass-casualty and active shooter events to prevent victims from dying of uncontrolled bleeding:

- T - Threat suppression

- H - Hemorrhage control

- RE - Rapid Extrication to safety

- A - Assessment by medical providers

- T - Transport to definitive care

This supports the evidence that hemorrhage control is of utmost importance in patients with ongoing bleeding and should be done before the assessment by medical providers. The ability to control bleeding profoundly increases the survival rates of patients with severe trauma. As such, everyone–from medical to non-medical personnel–is highly encouraged to be skilled in hemorrhage control techniques and trained to save a life.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ G. B. D. Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–210.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mock C, Lormand JD, Goosen J, Joshipura M, Peden M. Guidelines for essential trauma care. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004

- ↑ CDC: Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). In: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 https://www.aast.org/resources/trauma-facts

- ↑ World Health Organization., & Peden, M. M. (2004). World report on road traffic injury prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization

- ↑ Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB. Outcome after major trauma: 12-month and 18-month follow-up results from the Trauma Recovery Project. J Trauma. 1999, 46:765– 771; discussion 771–763.

- ↑ Vazquez Mata G, Rivera Fernandez R, Perez Aragon A, Gonzalez Carmona A, Fernandez Mondejar E, Navarrete Navarro P. Analysis of quality of life in polytraumatized patients two years after discharge from an intensive care unit. J Trauma. 1996;41:326 –332.

- ↑ https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-essential-trauma-care

- ↑ https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/atls

- ↑ Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, Cantrell J, Tops T, Uribe P, Mallett O, Zubko T, Oetjen-Gerdes L, Rasmussen TE, Butler FK, Kotwal RS, Kotwal RS, Holcomb JB, Wade C, Champion H, Lawnick M, Moores L, Blackbourne LH. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Dec;73(6 Suppl 5):S431-7.

- ↑ Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma. 2006 Jun;60(6 Suppl):S3-11. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19. PMID: 16763478.

- ↑ Spahn, D.R., Bouillon, B., Cerny, V. et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care 23, 98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2347-3

- ↑ Gutierrez, G., Reines, H. & Wulf-Gutierrez, M.E. Clinical review: Hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care 8, 373 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2851

- ↑ Johansson PI, Ostrowski SR, Secher NH. Management of major blood loss: an update. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010 Oct;54(9):1039-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02265.x. Epub 2010 Jul 6. PMID: 20626354.

- ↑ Davis JS, Satahoo SS, Butler FK, Dermer H, Naranjo D, Julien K, Van Haren RM, Namias N, Blackbourne LH, Schulman CI. An analysis of prehospital deaths: Who can we save? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014 Aug;77(2):213-8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000292. PMID: 25058244.

- ↑ Kragh JF Jr, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Fox CJ, Wade CE, Salinas J, Holcomb JB. Survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. Ann Surg. 2009 Jan;249(1):1-7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818842ba. PMID: 19106667.

- ↑ Kragh JF Jr, O'Neill ML, Walters TJ, Dubick MA, Baer DG, Wade CE, Holcomb JB, Blackbourne LH. The military emergency tourniquet program's lessons learned with devices and designs. Mil Med. 2011 Oct;176(10):1144-52. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00114. PMID: 22128650.

- ↑ Montgomery HR, Hammesfahr R, Fisher AD, Cain JS, Greydanus DJ, Butler FK Jr, Goolsby C, Eastman AL. 2019 Recommended Limb Tourniquets in Tactical Combat Casualty Care. J Spec Oper Med. 2019 Winter;19(4):27-50. PMID: 31910470. Categories

- ↑ https://www.facs.org/about-acs/hartford-consensus