Seawater greenhouse is a new form of technology, invented by Charlie Paton that can help to address water scarcity and quality problems. So far this form of technology has only been implemented in a handful of pilot systems around the world and all of these are still currently in progress; however, they show extremely high promise in the areas they have been deployed and give hope for the struggles of the people living in arid lands. Currently, there is no determined limit to the applications or the lifetime of the greenhouses. Thus, seawater greenhouses are not applicable everywhere.

Seawater greenhouses vary a fair amount from the conventional Dutch greenhouses, which is what the public normally associates greenhouses with. The differences though, are pretty astounding as they work in similar, but much more sustainable ways. They can be cheaper than the standard Dutch Greenhouse, they provide free water with no upkeep costs and without running into the carbon dioxide constrictions that Dutch greenhouses typically run into.

How It Works[edit | edit source]

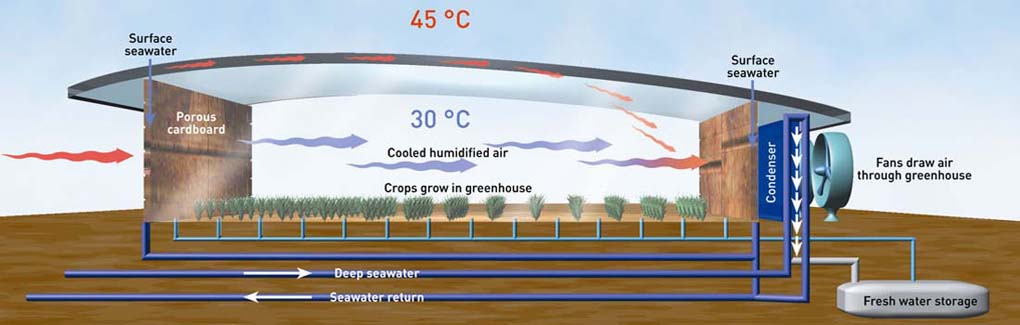

Like conventional greenhouses the seawater greenhouse creates and maintains its own climate separate from the desert outside. However, in a conventional greenhouse this is achieved through careful temperature and humidity control. In a seawater greenhouse, a cool humid climate is established by the evaporation of seawater by hot dry air incoming to the greenhouse. The seawater is first run through the roof of the greenhouse where it can absorb some of the heat that would otherwise heat the crops. Then it is dripped over a porous wall on one end of a structure. This is to maximize the contact between seawater and air, which will maximize evaporation and therefore cooling within the greenhouse. The wall is kept from fouling by the constant flow of water down it. The cooled, humidified air, flows through the greenhouse providing an adequate climate for the growing plants. At the other end of the greenhouse is a condenser, which is cooled by the seawater flowing to the evaporator at the other end. The condenser collects the humidity from the air in the form of freshwater, which is then collected and applied to the thirsty plants. The air flowing through the greenhouse however, is heated and dried by sunlight as it moves. This gives opportunity for a second evaporator to be placed in front of the condenser to boost its freshwater output. The total freshwater output of a greenhouse can be up to five times the amount needed for the plants inside [1]. The excess water can be effectively used to irrigate additional crops grown outside the greenhouse for consumption or even.

]

The only materials inputted into these greenhouses other than fertilizers and seeds, is seawater. This seawater can be pumped from the closest source including brackish groundwater. The pumping power is provided by an auxiliary solar array near the greenhouse. Thus the only inputs to a running greenhouse are seawater and sunlight, both are usually abundant in places which have high food demands and water shortages (i.e. coastal desert).

When the seawater from the greenhouses evaporates, salt and minerals are left behind. The salt can be sold as highly pure sea salt and the minerals can be recycled into the fertilizer for the plants [2]. When plants in the greenhouse are harvested, which happens 4-5 times a year, the food is taken and the remaining biomass can be composted for the recycling of nutrients.

Remediation[edit | edit source]

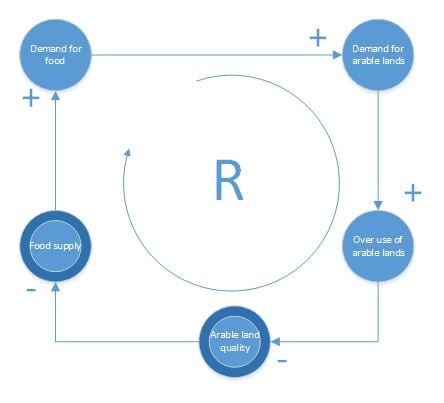

The system in West Sahara as it is now can be seen in figure 1, which contains a casual loop diagram. It shows that as the demand for food increases, so does the demand for arable lands to grow the food on. As the demand for land rises the tendency to over work the land to keep up with food demand becomes rampant. This overuse of agricultural land is detrimental to its quality and capacity to produce food products in the future. This reduction in food production inherently reduces the food supply which in turn increases the food demand. Thus the cycle perpetuates itself as a reinforcing loop, spiraling down into the sands of the Sahara.

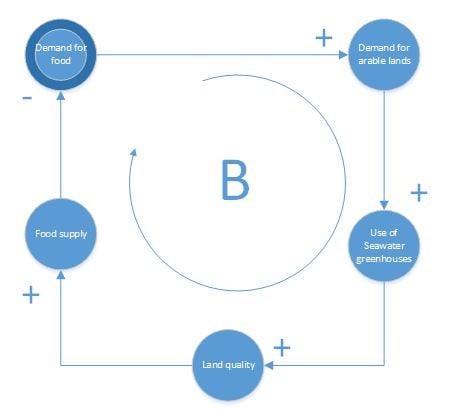

The social aspect is mainly promoted through the generation of food which is huge in this region due to the poverty of the people and the slowly dwindling means for them to make ends meet. The causal loop in Figure 2 depicts the system in Western Sahara after the implementation of seawater greenhouses. in the original system demands for food and lands increase as the quality of lands and the supply of food decreases. In the modified loop however "over use of arable lands" is replaced with "use of seawater greenhouses". This creates an increase in land quality due to remediative effects and then an increase in food supply from food grown inside the greenhouse and on the remediated land. The increase in food supply decreases food demand, effectively balancing the rest of the system by allowing it to eventually reach an equilibrium. With the modification of the causal loop that drives the food shortages of today, the people of Western Sahara would see much less death due to malnutrition and starvation.

See also[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

- [1] Jones, Gregory. 11 December 2012. "Worth its salt" Greenhouse Management. http://www.greenhousemag.com/Author.aspx?AuthorID=5931. Acessed: 22 April 2015.

- [2] Wang, Brian. 25 January 2012. "Seawater Greenhouses" Next Big Future. http://nextbigfuture.com/2012/01/seawater-greenhouses.html. Accessed: 22 April 2015.