Honey has a long and distinguished history in the human diet. For thousands of years honey hunters have plundered the hives of wild bees for their precious honey and beeswax - a practice still common today.

The most widely used honeybees are the European Apis mellifera, which have now been introduced worldwide. Tropical Africa has a native Apis mellifera, which is slightly smaller than the European Apis mellifera, and is more likely to fly off the comb and to sting. They are also more likely to abandon their hives if disturbed, and in some areas the colonies migrate seasonally.

In Asia there are three main native tropical species, Apis cerana, Apis dorsata, and Apis florea; cerana is the only species that can be managed in hives, but the single combs of the other two are collected by honey hunters.

There are three different kinds of bees in every colony: a queen, the drones, and the workers. The queen's job is to lay eggs, as many as several hundred in a day. These larva develop into drones, workers, or new queens, depending on how the workers treat them. Drones are the only male bees in the hive, and their main function is to mate with a virgin queen outside the hive. They die after mating. They have no sting, do not carry pollen, are unable to produce wax, and when resources are scarce they can be driven out of the hive to die. The all-female worker bees, make up about 98 per cent of the colony, and they do almost all the work. They bring water, pollen, nectar, and propolis (bee glue) back to the hive, while some remain to guard the hive, and some clean it, build the wax comb, nurse the young, and control the temperature of the hive. Workers eat honey to produce heat in cold weather and fan their wings to keep the hive cool in hot weather. Their legs are specially equipped with pollen baskets, and they have glands that produce wax on their abdomens. The worker has a sting, but usually dies after stinging anything.

A honey bee nest consists of a series of parallel beeswax combs. Each comb contains rows of wax with hexagonal compartments containing honey stores, pollen, or developing bee larvae (brood). To thrive and produce honey the bees need adequate supplies of nectar, pollen, and water. The combs are evenly spaced and are attached to the ceiling of the nest. The space between the faces of the combs is known as the 'bee space'; it is usually between 6 and 9mm and is critical in maintaining optimal conditions within the nest, with just enough space for bees to walk and work on the surface of the combs while maintaining the optimum nest temperature. Bee-space, dimensions of combs, and nest volume all vary with the race and species of honey bee. The bee-space is a crucial factor in the use of bee equipment, and honey bees cannot be managed efficiently using equipment of inappropriate size. Be careful! Most equipment is manufactured to the specifications of European bees.

Bees need a supply of food and water to live, and during dry periods the beekeeper may have to supplement natural sources. As a general rule, attempts to begin beekeeping should start with the area's existing bees, techniques, and equipment, which will all have been adapted for the local circumstances.

Equipment[edit | edit source]

Most of the equipment needed for small-scale beekeeping can be made at village level. It can be helpful to import basic equipment to serve as prototypes for local manufacturers. For practising on a large scale, some specialised equipment will probably need to be bought, such as honey gates, special filtering gauze, and gauges to determine honey quality.

Smoker[edit | edit source]

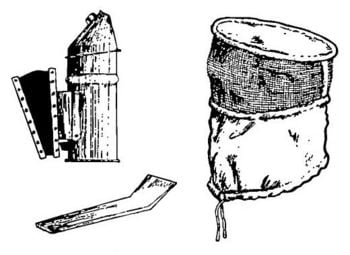

A beekeeper uses a smoker to produce cool smoke to calm the bees. The smoker consists of a fuel box containing smouldering fuel (for example dried cow dung, hessian, or cardboard) with a bellows attached. The beekeeper puffs a little smoke near the entrance of the hive before it is opened, and gently smokes the bees to move them from one part of the hive to another.

Protective clothing[edit | edit source]

Adequate protective clothing gives beginner beekeepers confidence, but more experienced beekeepers find that too much protective clothing makes it difficult to work sufficiently gently with the bees, and it is very hot. Always wear white or light-coloured clothing when working with bees - they are much more likely to sting dark-coloured clothing. It is most important to protect the face, especially the eyes and mouth; a broad-rimmed hat with some veiling will suffice. Individual items of clothing must be impermeable to bee stings, and every joint between them must be bee-tight; rubber bands can prevent bees from crawling up trouser legs or shirtsleeves. Some people find that a good way to protect their hands is to put a plastic bag over each hand, secured at the wrist with a rubber band.

Hive tools[edit | edit source]

The hive tool is a handy piece of metal which is used to prise boxes apart, scrape off odd bits of beeswax, separate frame-ends from their supports, and so on. They can be made from pieces of flat steel, and screwdrivers are often used. It is possible to use an old knife for this job, but knife blades tend to be too flexible and give insufficient leverage.

Beehives[edit | edit source]

A beehive is any container provided for honey bees to nest in. The idea is to encourage the bees to build their nest in such a way that it is easy for the beekeeper to manage and exploit them.

Traditional hives[edit | edit source]

These are made from whatever materials are available locally: typically hollowed-out logs, bark formed into a cylinder, clay pots, woven grass, or cane. They are used to encourage bees to nest in a site that is accessible by the beekeeper.

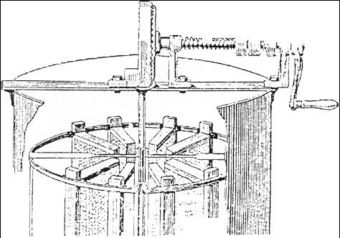

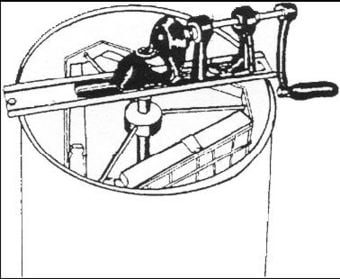

Movable frames can be spun in a radial (a) or tangential (b) extractor Both of these can be adapted to take comb from the top bar hives by making wire mesh cages that sit where the frames normally would A third option (not shown) is for flat, round mesh trays that stack inside the cylinder.

The bees build their nest inside the container, just as they would build it in a naturally occurring cavity. Eventually the beekeeper plunders the nest to obtain crops of honey and beeswax. Bees may or may not be killed during this process, depending on the skill of the beekeeper. If the colony is destroyed, the hive will remain empty for a while. If there are plenty of honey bee colonies in the area, then eventually a swarm may settle in the empty hive and start building a new nest. Traditional beekeepers often own 200 hives, and expect only a proportion of these to be occupied by bees at any time.

All the requirements for traditional beekeepers will be available locally, but beekeepers can be helped by the provision of protective clothing, smokers, and containers for the honey, and with help in locating markets for their products.

Movable frame hives[edit | edit source]

These are the hives used in industrialised countries and in some countries in the South where beekeeping is a major industry, such as Mexico and Brazil. The objective of movable-frame hive beekeeping is to obtain the maximum honey crop, season after season, with the least disruption of the colony. These rectangular wooden or plastic frames have two major advantages:

- They allow easy inspection and manipulation of colonies.

- They allow very efficient honey harvesting because the honeycombs, within their frames, can be emptied of honey and then returned to the hive.

Frame hives must be constructed with precision. Frames are contained within boxes and each hive consists of a number of boxes placed on top of each other. Often a 'queen excluder', a metal grid with holes that allows only the smaller worker bees to pass through, is used to isolate the brood in the bottom-most boxes. The rest of the boxes will contain only honey.

Intermediate technology hives[edit | edit source]

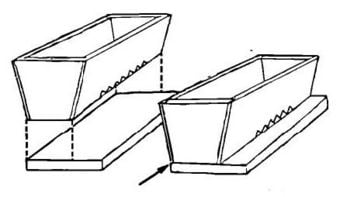

Intermediate technology hives combine the advantages of frame hives with low cost and the ability to manufacture locally. The hive consists of a container with a series of 'top bars', on which the bees are encouraged to build their combs. These top bars then allow individual combs to be lifted from the hive by the beekeeper. The containers for the hives may, like traditional hives, be built from whatever materials are locally available. Top-bar hives can also be kept near the home and moved between flowering crops, enabling women to keep bees.

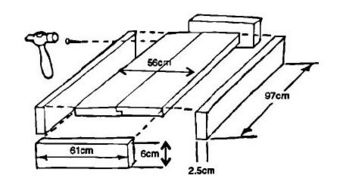

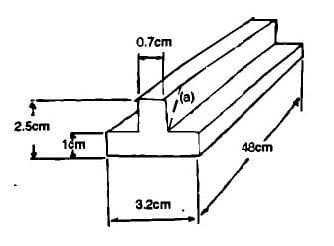

The only items in the top-bar hive which need to be built with precision are the top bars themselves; they must provide the same spacing of combs within the hive as the bees would use in their natural nest. The natural comb spacing is the distance between the centres of adjoining combs, and this spacing will depend upon the species and race of honey bees which are being used. As a very general guide, Apis mellifera of European origin need top bars 35mm wide, Apis mellifera in Africa need 32mm, and Apis cerana in Asia need 30mm. The best way to determine the optimum width is to measure the spacing between combs in a wild nest of the same bees. The volume of the brood box should equate roughly with the volume of the cavity occupied by wild-nesting honey bees.

Making a start[edit | edit source]

A good way to begin beekeeping, especially in Africa, is to bait an empty hive to attract a swarm. Set up a hive and either rub it inside with some beeswax or lavender to give it an attractive smell, or leave some attractive food for the bees: granulated sugar or cassava powder will work. You could also put some honey on the tops of the top bars. The bees will not be able to get at it and take it away to another hive, but the scent will still remain to attract them. This will only be successful in areas where there are still plenty of honey bee colonies. Another option is to transfer a colony from the wild into the hive. The wild colony will already have a number of combs and these can be carefully tied on to the top bars of the hive, making sure that you include the brood combs and the queen. One of the best ways to get started in beekeeping is with the assistance of a practising, local beekeeper.

Harvesting honey and beeswax[edit | edit source]

Honey is harvested at the end of a flowering season. The beekeeper selects those combs which contain ripe honey, covered with a fine layer of white beeswax. These combs are usually the outside-most ones. Combs containing any pollen or developing bees should be left undisturbed. Honey will keep a long time if it is clean and sealed in an airtight container, but will deteriorate rapidly and ferment if it has absorbed water. Preventing this from happening is crucial in honey harvesting.

Harvesting the combs[edit | edit source]

Harvesting should be carried out in the evening or the early morning. Gentleness is the key to successful colony manipulation, so learn to carry out this process swiftly but calmly to avoid upsetting your bees.

- Put on your protective clothing.

- Get your smoker, brush or quill, knife or hive tool, and a rust- proof container in which to put the honeycomb.

- Load your smoker, and puff some smoke gently around the hive for a few minutes. Wait a few more minutes, then puff smoke around the entrance holes.

- After puffing the smoke, open the lid.

- Knock the top bars to see which of them have combs; they will sound heavier than empty ones.

- Use the knife or hive tool to remove the first bar from one end of the hive.

- Puff smoke gently into the gap to drive the bees to the other side of the hive.

- Start removing the bars one by one, until you get to the first comb, which will be white and new. It may be empty or it may contain some unripened honey. Replace it and leave the comb for the bees to develop.

- Remove only the capped or partly capped combs, which will be quite heavy. Use a brush or feather to sweep any bees back into the hive.

- Cut the comb off, leaving about 2cm for the bees to start building on again. Put the comb in a container and replace the top bar.

- Carryon harvesting until you come across a brood comb,

- which will be dark in colour and contain pollen too. Leave this honey for the bees.

- Start the process again at the other end of the hive.

- Close the hive carefully, replacing the lid.

Honey extraction[edit | edit source]

The honeycomb can be simply cut into pieces and sold as fresh, cut comb honey. Alternatively, the honey and comb can be separated and sold as fresh honey and beeswax. It is important when processing honey to remember that it is hygroscopic and will absorb moisture, so all honey processing equipment must be perfectly dry.

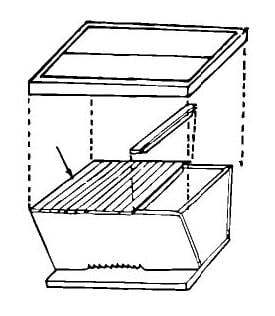

The most common traditional methods of honey extraction are squeezing or burning the combs. Burning the honeycomb is wasteful and makes the quality of both the wax and the honey inferior; it should be avoided at all costs. If your quantity of honey or financial resources are small, then squeezing the honey out by hand is probably the most viable option. The honey extracted by this method will have to be strained through several increasingly finer meshes to remove any bits of wax or debris, ending with something like muslin cloth. It is very important that this procedure be carried out hygienically, and that the honey is not left exposed to the air, where it will pick up moisture and deteriorate. Another good way of extracting honey from top-bar or movable frame hives is a radial or tangential extractor. This is a cylindrical container with a centrally-mounted fitting to support combs or frames of uncapped honey, and a mechanism to rotate the fitting (and the combs) at speed. The honey is thrown out against the side of the container and runs down to the bottom, where it is collected and then drained off with a tap. Most manufactured extractors are made to hold frames and have to be adapted to take comb from top bar hives. This is usually done by making wire baskets to hold the comb. The baskets can either lie flat horizontally, or be attached to the vertical frames and sit tangentially within the container. Top-bar combs in tangential extractors have to be spun twice, once on each side, to extract all the honey.

The honey must be stored in airtight, non-tainting containers to prevent water absorption and consequent fermentation. If you want to sell your honey it would be helpful to add a label describing the source of the honey (for example sunflower, mixed blossom, tree honey), the country and district it was produced in, the weight or amount of honey in the container, and your name and address.

Beeswax extraction[edit | edit source]

The comb from which bees build their nest is made of beeswax. After as much honey as possible is separated from the combs, the beeswax can be melted gently over moderately warm water (boiling water will ruin the wax) and moulded into a block.

Another option for processing the wax is a solar wax melter (Figure 4). This appliance is easy to make and consists of a wooden box with a galvanised metal shelf with a spout, a bowl or container that sits under the spout, and a glass or plastic cover. When placed in the sun the temperature inside the box will melt down a comb and the wax will flow into a container inside the box. Any honey that was left in the combs will sink to the bottom; it is usually used for cooking or beer making as its taste is spoiled somewhat by this process.

Beeswax does not deteriorate with age and therefore beekeepers often save their scraps of beeswax until they have a sufficiently large amount to sell. Many beekeepers still discard beeswax, unaware of its value. Beeswax is a valuable commodity with many uses in traditional societies: it is used in the lost-wax method of brass casting, as a waterproofing agent for strengthening leather and cotton strings, in batik, in the manufacture of candles, and in various hair and skin ointments. Beeswax is also in demand on the world market. Beeswax for export should be clean and have been re-heated as little as possible.

Bee stings[edit | edit source]

Bee stings can be avoided by wearing protective clothing, but if you are stung, you should remove the sting as soon as possible by scraping it off with a fingernail or knife. Do not try to pick it off as you may squeeze poison into your flesh. Some steps to help avoid bee stings are:

- Wash yourself to make sure you are free of odours.

- Do not use any cosmetics, perfume, etc.

- Approach the hive from the side or behind the entrance.

- Do not wear dark clothing.

- Approach the hive quietly.

- Provide bees with water during the dry season.

- Be careful not to crush a bee, as it gives off an alarm scent.

If you are stung, you should move away and remove the sting, as other bees will be attracted by the powerful smell that the bee leaves on the spot where you have been stung. As soon as the sting is out, the site should be smoked to disguise the alarm pheromone.

If you are allergic to bee stings, you should not take up beekeeping.

Disease and pests[edit | edit source]

During the last two decades there has been a tremendous increase in the spread of bee disease around the world. This has been brought about by the movement of honey bee colonies and used beekeeping equipment by people. There are few remaining regions without introduced honey bee diseases, and as a rule used beekeeping equipment should not be imported.

Honey bee colonies, or even single queen bees, must never be moved from one area to another without expert consideration of the consequences.

There are numerous pests that will disrupt a beehive and prey on your bees. Wax moths are almost universal, ants a very common and persistent hazard, and honey badgers a serious nuisance in Africa. It is best to talk to other local beekeepers about what the most common problems are and take their advice about appropriate defences.

References and further reading[edit | edit source]

- Honey Processing Practical Action Technical Brief

- Tools for Agriculture; 4th Edition Practical Action Publishing, 1992

- The Golden Insect by Stephen Adjare, Practical Action Publishing, 1984

- Beekeeping in the Tropics; Agrodok 32, Agromisa Foundation

This Technical Brief was originally published in the Appropriate Technology Journal Volume 20. Number 4 March 1994 AT Brief No 7.

For more information about Appropriate Technology contact: Research Information Ltd. 222 Maylands Avenue Hemel Hempstead, Herts. HP2 7TD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 8328 2470 Fax: +44 (0)1442 259395 E-mail Website1 Website 2

Our thanks to Andrew Matherson, Director of IBRA, whose helpful comments on a draft of this AT Brief resulted in a much improved product, but who is not responsible for any inaccuracies in the final version.

See also[edit | edit source]

- Native beekeeping; a more environmentally-friendly way of beekeeping

- Beekeeping

- Make your own Honey Cow (Top Bar Bee Hive)

- Open Source Beehives