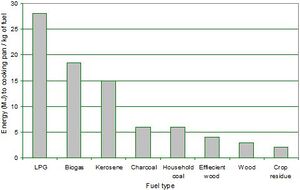

The vast majority of people in developing countries use biomass fuels for all their energy requirements. These incorporate a wide range of fuels such as fuelwood, charcoal, crop residues and animal dung. In rural areas few other fuel sources are available or affordable. However, as people's incomes grow they begin to use 'modern' fuels more extensively. When people can afford kerosene and gas (LPG) they prefer these fuels to fuelwood or dung for cooking. As can be seen from figure 1, kerosene and LPG are many times more efficient, less damaging to the health and are much easier to use for cooking. Kerosene is also widely used for lighting in developing countries.

Technical[edit | edit source]

How kerosene and gas were formed, and are extracted and refined[edit | edit source]

Petroleum crude oil and natural gas are the products of hundreds of millions of year's work on organic material that collected in many regions throughout the world. These organic materials, usually the remains of animal and plant life, have been subjected to heat and pressure and during this time the constituent fats, carbohydrates and proteins have decomposed and undergone extensive chemical changes. Petroleum and natural gas, therefore, vary in their chemical characteristics due to the original composition of these organic materials and due to further action by various ferments and bacteria. As well as providing a wide range of combustible fuels, petroleum is processed to provide materials for a variety of other products: synthetic rubbers and fibres, plastics, solvents, etc. Following extraction, the crude oil is transported to the refinery. It is first subjected to sedimentation to remove all water and solid particles and then distilled to extract all the readily volatile petrol constituents, gases (from which LPG is obtained) and kerosene (also known as paraffin oil). The refining process is then a complex procedure to remove all further impurities and obtain a usable product. Natural gas is extracted as a product in its own right and is put to many uses, such as powering electricity generating plant, industrial applications, domestic use and many others.

Kerosene comes in liquid form. It is usually transported in bulk and in rural areas of developing countries is usually purchased by the litre or bottle. It is commonly found in rural centres and is used in most LDC's where it is sold by small retailing outlets or garages.

Kerosene is used mainly for cooking and lighting. An appropriately designed kerosene stove can be efficient and cook quickly, they are easily controlled, convenient and popular in comparison with other rural cooking technologies. Using kerosene can prevent illnesses related to a smoky environment, will help save trees and cuts down the time required for fuelwood collection in areas where fuelwood is already scarce. On the other hand, kerosene stoves give off an unpleasant smell and can be dangerous when handled improperly or when faulty equipment is used. Lighting a kerosene stove is also tedious and they can be noisy when running. The cost of purchasing kerosene is prohibitive in many parts of the developing world and quality is often poor.

Liquid petroleum gas (LPG) or bottled gas comprises butane or propane which are hydrocarbon gases produced during the petroleum refining process mentioned above. They are gaseous at normal temperatures but when compressed become liquid. It is typically purchased in cylinders of various sizes: 2.7kg, 6kg, 12kg, 16kg, up to 47.2kg. LPG is used predominantly for cooking and is very easy to use, is efficient and burns cleanly. It is not commonly found in rural areas but is used amongst middle or high income groups in urban areas. The high initial cost of purchasing appliances and cylinders, relatively sophisticated technology, irregularity of supply and risk of explosion mean that it is not widely used in the majority of poorer areas. Cylinders are usually exchanged at filling stations and since there are few of these in rural areas and transport is poor, access to this fuel source is also difficult.

Hardware[edit | edit source]

Kerosene There are various types of stoves and lamps available, and these will vary from country to country. There are two main types of stove - the wick stove and the pressurised stove. There is little to choose between the two. The pressure stove is more powerful but also generally more expensive and more prone to accidents due to the complexity of the lighting technique and the pressurised contents. A brief description of each kind of stove is given below.

The wick stove[edit | edit source]

Wick stoves can have one or more wicks. Improved kerosene wick stoves can have up to 30 or 40 wicks and produce a maximum power of around 5kW with an efficiency of up to 50%. A common design incorporates a series of wicks, usually made of loosely twisted or woven cotton, placed in a holder such that they can be moved up and down by a control lever or knob. They emerge into an annular space surrounded by two concentric perforated steel walls (the flame holder) which are spaced slightly wider than the wick thickness. The lower part of the wick sits in a kerosene reservoir. The whole unit is situated inside a suitably designed potholder and casing which will have legs to allow the stove to sit easily on an uneven floor.

The stove is lit by removing the perforated steel flame holder, raising the wicks and lighting them. The holder is then replaced. The flames fill the gap between the two walls of the holder and emerge at the top of the stove. The flame can be raised or lowered by operating the lever; when raised the flame burns more intensely and vice versa. The flame will normally burn a blue colour but if raised too high the flame will become yellow and soot will be given off. After normal operation for some time, the flame holder will glow red-hot.

The kerosene pressure stove[edit | edit source]

The standard kerosene pressure stove comprises a fuel tank (which can be pressurised by means of a hand-operated plunger pump), a vapour burner and a pot holder (see Figure 3). Vaporised kerosene fuel is passed under pressure through a nozzle and mixes with primary air to form a strong blue flame. To initiate the process the vaporiser has to be preheated using an alcohol based flame which burns for several minutes in a tray placed below the vaporiser. Once the temperature of the vaporiser is raised sufficiently the kerosene can then be vaporised by the heat of the cooking flame and the alcohol flame can be allowed to extinguish. The pressure forces kerosene through the vaporiser continuously and is controlled by the adjustment valve or by regulating the pressure of the tank, which in turn controls the flame intensity. Again there are various designs based on the same operating principle, some with more than one vaporiser fitted to provide multiple cooking rings. Another means of pressurising the kerosene is to use a header tank. This does away with the need for a pressurised tank but also makes the stove more cumbersome. Typical maximum power output is in the range of 3 -10 kW.

To assess the technical performance of kerosene stove, the following factors need to be considered:

- maximum power

- efficiency at different power outputs

- ability to control power output - known as the turn-down ratio

- safety standards

The turn-down ratio is important as food often has to be simmered at low power output.

Kerosene lighting[edit | edit source]

The options are similar when we look at kerosene lighting technology. The two main lamp types are the wick and pressure lamps. The pressure lamp, commonly known as the 'Tilley' or 'Petromax' lamp works on the same principle as the pressurised stove but the flame emerges inside an incandescent mantle which provides visible light.

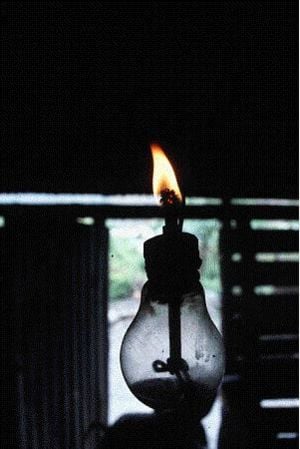

The wick lamp comes in various forms - from the simple, locally made, 'wick-in-a-can' (See figure 4) to the more sophisticated 'storm (or hurricane) lantern'.

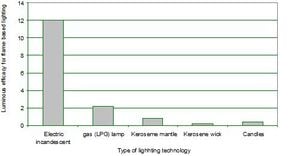

The efficiency of such lamps tends to be very low. Figure 5 (over) shows a comparison of the luminous efficacy of various types of lighting technology.

LPG[edit | edit source]

As mentioned earlier, LPG is not currently widely used in rural areas of LDC's. We will therefore only briefly look at this technology. LPG cooking stoves come in various shapes and sizes; the most common being the Camping Gaz variety. These have a simple burning ring, pan support and use a 3 or 6 kg LPG bottle (See figure below). Multiple ring stoves with combined oven are also common amongst higher income groups. Gas lamps use a similar rare earth incandescent mantle to the kerosene pressure lamp because the gas otherwise burns with a blue nonluminous flame. Again Camping Gaz is a common brand name and the lamps tend to be of simple construction with the mantle holder and valve assembly fitted directly to the bottle.

Another application for LPG is refrigeration. The gas is used as a heating source in conjunction with an absorption refrigeration cycle to provide cooling for vaccines in hospitals (and cold drinks!). Gas can also be used for sterilisation processes in hospitals.

Manufacturing and engineering requirements[edit | edit source]

It is obviously beneficial to the local economy and community if stoves can be manufactured locally using materials available in the region. If the guidelines given below are adhered to then no problems should be encountered with local manufacture. In many countries throughout the world, however, conditions are not suitable for in-country manufacture and local craftsmen are usually unable to compete with imported, usually Chinese or Indian, stove prices.

Whether considering a pressure or wick stove certain requirements should be fulfilled for the stove to be considered suitable in a given situation. Below are some guidelines:

Usage and performance[edit | edit source]

- may be either a wick or pressure stove.

- suitable for the type of pots commonly found in the region - this usually means that a variety pots of various shapes and sizes can be accommodated on the stove. The pot should stand firmly on the stove even when being stirred vigorously.

- should be easy to ignite and preferably not require a separate starting fuel - it should also be easy to light in a wind.

- maximum power sufficient for cooking meals in pots of the largest common size.

- low specific energy consumption at high power.

- low fuel consumption when simmering.

- easy power regulation - suitable turn-down ratio.

- no unintended flame extinguishing at low power, even in wind.

- no very hot outer parts.

- easy placing and removal of pots without getting burnt.

- good quality combustion - no smoke, smell or emissions.

- low fuel indicator.

- easy filling of fuel - even when hot.

- stable on a variety of surfaces.

- simple instruction for use.

- no danger of fires or spillage even if mishandled.

- durable - life span of several years

Maintenance and servicing[edit | edit source]

- simple maintenance and cleaning.

- should withstand boiling over of food.

- free moving, reliable, mechanical moving parts.

- tolerant of sand, dust, etc. in the fuel.

- tolerant of moderate mishandling and being left unused for a long time.

- repairable by owner - simple wearing parts at least e.g. wick.

- simple spares, easily available and fitted at local retailer.

- designed to use standard items and spares e.g. wicks, seals, etc.

- no complicated tools or training required for maintenance.

- exchangeability of parts between different models.

- not possible to reassemble wrongly.

Manufacture[edit | edit source]

- local manufacture as far as possible.

- manufacturing techniques to match those available locally.

- where possible to be manufactured within the informal sector.

- a competitive price.

- no complex manufacturing techniques which need special equipment or training.

- use of locally available materials - clay, reclaimed metal, etc.

- durable - should have a life of at least 3 years

(Source: Dr Eric T. Ferguson, Requirements for Kerosene Stoves for the Sahel, 1988, Boiling Point 20)

Other issues[edit | edit source]

Subsidies[edit | edit source]

Government subsidies are sometimes used to reduce the cost of a fuel to encourage its use. This is often the case in countries where there are shortages of traditional fuel sources or where the government feels a need to modernise the energy sector. These subsidies can often be counterproductive as they are expensive for the government, often eating up significant portions of the national budget, and limit the quantity of fuel available. Some argue that market liberalisation is a more effective way of encouraging a change in fuel use habits.

Available alternatives[edit | edit source]

An alternative to encouraging the use of 'modern' fuels is to provide low-cost methods of improving the efficiency and desirability of traditional fuel combustion technologies. Much work has been carried out throughout the developing world on improved stoves for use with biomass fuels. The main thrust of the work has been to improve efficiencies (to reduce fuel consumption and hence collection times) and to remove smoke from the user environment (to tackle the health problems associated with traditional fuel use). Many improved biomass stove techniques have been developed and adopted throughout the world. The availability and comparative cost of such stoves directly affects the need and the desire to change to modern fuel sources. (See the fact sheet on improved stoves).

Practical Action would like to acknowledge The British Council and DFID as funders and ITC as Project Co-ordinators for the production of this technical brief.

References and resources[edit | edit source]

- Louineau, J., Dicko, M., et al, Rural Lighting, IT Publications and The Stockholm Environment Institute, 1994

- Rural Energy and Development, The World Bank, 1996.

- Kerosene and gas stoves in Nagercoil, South India. Article, Boiling Point (BP) No.20, December 1989.

- Kerosene wick stoves, Article, Boiling Point (BP) No.20, December 1989.

- An investigation on the Colombian kerosene stove. Article, Boiling Point (BP) No.20, December 1989.

- Kerosene stoves in Ethiopia, Article, Boiling Point (BP) No.32, January 1994.

- Floor, W., and van der Plas, R., Kerosene Stoves: their performance, use andconstraints, Joint UNDP / World Bank Energy Sector management Assistance Program, October 1991.

- Westhoff, B. And Germann, D., Stove Images, Commission of the EuropeanCommunities

- Rural Lighting, (Practical Action Technical Brief)