Riparian and in-river flood management measures. Rivers themselves can serve a flood management function by providing "live storage." The open space of floodplains adjacent to rivers and streams store and slowly release floodwaters, reducing peak flood flows downstream. Wetland areas act as large sponges, soaking up floodwaters in addition to filtering water and adding to groundwater supplies. Many flood management measures constructed in the past reduced the natural live storage capacity of river channels. When engineers cut off meanders to straighten rivers and increase flow velocities, the storage provided by the longer, meandering river channel is lost. Levees constructed to keep rivers within their channels prevent floodplains from storing and slowly releasing flood flows. As a result, in some cases peak flood flows have increased and caused greater flood risk downstream of highly controlled river reaches. This transferring of the flood creates a feedback loop of escalating flood risk and flood management actions that propagates downstream.[1] By restoring the natural flood-carrying capacity of rivers and/or their riparian buffer regions, the need for a new or existing dam is reduced.

In more recent efforts to restore natural river functions, including providing instream storage, the trend has reversed. The most common measures recommended today, which are discussed below, include:

- Breaching or setting back levees;

- Restoring meanders;

- Constructing bypass channels; and

- Restoring vegetated banks and wetlands.[2]

Breaching levees[edit | edit source]

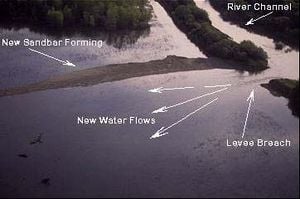

Many river restoration and flood management projects involve breaching or removing portions of levees to allow the river to reconnect with its floodplain, thereby recreating the temporary flood storage function and important floodplain habitat.

Advantages[edit | edit source]

Breaching levees can be a relatively inexpensive measure in many cases, involving only several hours of operating a backhoe or bulldozer. Temporarily flooding old floodplains will produce many secondary benefits such as increasing groundwater infiltration, improving water quality, restoring natural floodplain forming processes (e.g., sediment transport and deposition) and improving fish and wildlife habitats.

Disadvantages[edit | edit source]

In many cases the area to be inundated again with a levee breach has been developed, requiring other levees to limit the area to be flooded. Many levees today also have secondary functions, such as an active roadbed, that would have to be accommodated somehow before breaching.

Costs[edit | edit source]

Costs will vary from thousands to millions of dollars depending on the size of the levee, the amount to be removed, whether the opening must be protected with engineered structures, whether the breach is to be open continuously or operated in response to certain events, and whether other measures are needed to control the flooding allowed by the new

Breaching levees case study[edit | edit source]

The Cosumnes River Project in California was started in 1987 after The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and its partners established the Cosumnes River Preserve with the goal of restoring and protecting the river system. As part of the project, TNC scientists breached a riverside levee along the Cosumnes River in California during the winter of 1995-6, allowing the river to flow through a 50-foot long gap into a former farm field.[3] More levees have since been breached or have been set back to create a larger floodplain.[4] As a result of the levee breaching, the natural process of flooding has resumed, allowing restoration of plant, fish and wildlife populations, as well as restoring a floodplain for excess water storage.11[3]

To learn more about this project, visit The Nature Conservancy at http://www.tnccalifornia.org/our_proj/cosumnes/ or Cosumnes River Preserve at http://www.cosumnes.org or contact Ramona Swenson with The Nature Conservancy at 916- 684-4012.

Where you can go for help[edit | edit source]

- For more information, contact your state natural resources agency, such as Department of Natural Resources or Department of Environmental Protection.

- Cosumnes Research Group

- Florsheim, J.L. and J.F. Mount (2002), Restoration of floodplain topography by sand splay complex formation in response to intentional levee breaches, Lower Cosumnes River, California: Geomorphology, v. 44, p. 67-94.

Setting back levees[edit | edit source]

Many river projects also involve moving levees away from rivers (setting back levees) to provide more floodplain area to store floodwaters and to restore some of the habitat complexity characteristic of natural rivers.

Advantages[edit | edit source]

Setting levees back can serve the dual purpose of creating more favorable habitat for fish and wildlife and increasing the channel's flood capacity, thereby reducing flood water levels. Depending on the river system and the amount of storage capacity created, this could eliminate the need for new or existing flood management dams.

Disadvantages[edit | edit source]

The principal drawback of levee setbacks is often the cost, as moving large amounts of the material that makes up levees can become expensive. The planning and engineering design for the reconfigured channel can also be costly. In addition, setting levees back far enough to have a meaningful impact on flood flows can require a significant area, which can conflict with current land uses. The cost of levee setbacks will vary from thousands of dollars to many millions, depending on the size of the river and setback to be implemented.

Setting back levees case study[edit | edit source]

The California cities of Marysville and Yuba City are situated near the confluence of the Sacramento, Feather, and Yuba rivers, and, as a result, have experienced numerous devastating floods. Regional stakeholders have developed a plan to set back several miles of levees along both banks of the Feather River, rather than build new dams or other flood management structures. Project modelers predict flood water levels will decrease up to four feet in certain areas once the project is completed.[5] The project is expected to cost more than $20 million.[6]

For more information, contact Janet Cohen with the South Yuba River Citizens League at 530-265-5961.

Restoring river meanders[edit | edit source]

Restoring meanders to impounded and/or straightened streams is becoming an increasingly accepted choice in flood management across the country. Many rivers have been so altered by flood management projects that significant restoration work may be required. The University of Mississippi, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has conducted successful research using vegetation of specific densities and patterns to encourage streams to alter their courses and sediment deposition, recreating "natural" meanders. Once a dam or other flood management project is removed, however, many rivers will naturally recreate an appropriate meandering channel relatively quickly without any assistance. Either way, increasing the natural capacity of the river can decrease the need for an existing or new dam.

Advantages[edit | edit source]

Restoring meanders to rivers that have been straightened not only restores river habitat degraded by past flood management projects, but also increases the instream storage capacity and slows the downstream propagation of the flood peak, thereby decreasing downstream flood risk and the need for flood management dams.

Disadvantages[edit | edit source]

Restoring meanders often requires large areas of land adjacent to the river, which could inhibit or eliminate existing uses of that land. In addition, it may be difficult to convince members of the community that flooding will not increase when a dam is removed. This is often the case, even when the dam provides no meaningful flood protection.

Costs[edit | edit source]

As discussed above, restoring rivers and stream meanders can cost anywhere from several thousand to many millions of dollars depending on the size of the project. For example, a project to restore natural meanders on the Soque River in Georgia cost $55,000 and involved the use of rock vanes and strategically placed vegetation.[7] On the other end of the spectrum, restoring the Omak Creek in Washington State to its original stream was more complex. The total project cost was $788,000, which included moving the stream back to its original channel, creating instream habitat, revegetation, and more.[8]

Restoring river meanders case study[edit | edit source]

North Richmond, California was established on the floodplains of Wildcat and San Pablo creeks on San Pablo Bay near San Francisco. Although this was a suitable location for the shipbuilding industry, the community frequently suffered from flooding in the winter months. After years of costly and ineffective flood management projects that damaged the environment, the County Board of Supervisors approved a community supported alternative flood management plan in 1985. The goal of the plan in this highly developed watershed was to use the creek's natural character as much as possible to handle 100-year flood flows, and to properly manage environmental stressors from these flows in order to allow the functioning of the ecosystem. Restoration techniques included restoring a meandering channel pattern that mimicked natural streams and riparian tree planting. The natural channel provides various aquatic habitats with its designed pools, riffles and glides while also transporting sediments away from vulnerable marshes and accepting higher flows onto floodplains. Trees were planted along the stream to guide channel formation, to prevent erosion, to lower the water temperature and to provide woody debris beneficial to river organisms. Not only was flood management achieved and riparian and habitat restored, but the project provided public education and aesthetic enhancement.[9]

To learn more about the North Richmond alternative flood management plan, visit http://web.archive.org/web/20100531175523/http://www.epa.gov:80/OWOW/NPS/Ecology/chap6wil.html.

Where you can go for help[edit | edit source]

- For more information, contact your state natural resources agency, such as Department of Natural Resources or Department of Environmental Protection.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture: http://web.archive.org/web/20040603054416/http://www.usda.gov:80/stream_restoration/newlnk.htm</ref>

- Rinaldi, M. and P.A. Johnson. "Characterization of Stream Meanders for Stream Restoration." Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 123(6): 567-570.

- Shore, D. and P. Wadecki. "Born Again River: Remeandering the Nippersink." Chicago Wilderness. Winter 2001: http://chicagowildernessmag.org/issues/winter2001/bornagainriver.html.

- National Technical Information Service. Stream Corridor Restoration - Principles, Processes, Practices: http://web.archive.org/web/20090306052704/http://www.ntis.gov:80/products/bestsellers/streamcorridor.asp?loc=4-2-0.

Constructing bypass channels[edit | edit source]

Bypass channels, which are alternate channels that a river or stream will utilize above certain flow levels, have been constructed to increase the discharge capacity of many rivers where flooding has been a problem. In the past, these were frequently no more than concrete-lined canals designed to carry flows with the least frictional resistance. More recently however, bypass channels are being designed to mimic natural channels and provide seasonal or permanent habitat for fish and wildlife. In some cases, rivers are being allowed to reclaim secondary channels that had been converted to agriculture or other uses.

Advantages[edit | edit source]

Whereas a dam is constructed to "catch" or impound floodwaters, a bypass channel replaces this function by creating an alternative overflow or "storage" channel for floodwaters. In addition to increasing flood capacity of a system, bypass channels can provide temporary fish and wildlife habitat. They can also serve other functions, such as providing additional farmland or parkland, when not needed to convey floodwaters.

Disadvantages[edit | edit source]

Bypass channels often require a large amount of land, a challenge in many areas. In addition, if the channel must be constructed or greatly improved, such projects can become expensive. In situations where farmland is to be used, it might be difficult to purchase the land or obtain a flood easement to allow occasional flooding. Finally, the potential exists for designing a project that is over engineered and does more harm to the environment (i.e., creation of concrete box channels or culverts).

Costs[edit | edit source]

Depending on the type of bypass project, costs vary widely and can reach into the millions of dollars. Along the Guadalupe River in San Jose, California, a 3,000-foot long bypass channel will be constructed to double the flood capacity in a heavily developed stretch of river at a cost of $225 million. This cost is on the high end of the spectrum because it includes relocating numerous businesses and residences.[10]

Constructing bypass channels case study[edit | edit source]

Constructed in the early 1930's, California's Yolo Bypass serves to convey floodwaters for the Sacramento and Feather Rivers. The Army Corps of Engineers developed a network of weirs and bypass channels that would mimic the natural hydrology of the Sacramento River. As soon as the combined flow from the Sacramento River and Feather River reach a certain trigger point, floodwaters are diverted to the Yolo Bypass. While the maximum flow capacity for the main channel of the Sacramento River is 110,000 cfs, the Yolo Bypass can convey 490,000 cfs. Though the Sacramento River has exceeded its flow capacity every other year on average from 1956 to 1998, the Yolo Bypass has yet to exceed its capacity. In addition to its flood management benefits, the bypass and area wetlands serve as critical habitat for migrating fowl, steelhead, chinook salmon, and delta smelt.[11]

To learn more about the Yolo Bypass, contact Ted Sommers with the Department of Water Resources at 916-227-7537 or tsommer@water.ca.gov or Elizabeth Soderstrom with the Natural Heritage Institute at 530-478-5694 or esoderstrom@n-h-i.org.

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mount, J.F. California Rivers and Streams: the conflict between fluvial process and land use. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- ↑ Interagency Floodplain Management Review Committee. Sharing the Challenge: Floodplain Management into the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1994.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Consumnes River Preserve, Consumnes River Project and Mission, http://www.cosumnes.org/ (11 June 2002).

- ↑ The Nature Conservancy of California, "Cosumnes Preserve Gets New Partners, New Lands—More than Doubles in Size," California Newsletters, 1999, http://www.tnccalifornia.org/news/newsletters/newsletter_summer_1999.asp> (11 June 2002).

- ↑ Sacramento River Portal, Sacramento River Project Reports, http://www.sacramentoriverportal.org/modeling/hydro_index.htm (19 June 2003).

- ↑ Janet Cohen, Executive Director, South Yuba River Citizens League, personal communication, 14 March 2003.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency, Natural Restoration on the Soque River, Georgia, http://www.epa.gov/region4/water/wetlands/projects/soqueepa.html (15 March 2004).

- ↑ Alvarez, S.M. and B. Ridolfi, Omak Creek Relocation Project: Forming a Stream Team to Rebuild Steelhead Runs, http://www.ridolfi.com/omak/ (15 March 2004).

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency, Ecological Restoration: A Tool To Manage Stream Quality; Wildcat Creek, California, July 2002, http://web.archive.org/web/20100531175523/http://www.epa.gov:80/OWOW/NPS/Ecology/chap6wil.html (17 July 2003).

- ↑ "Flood control project to resume in San Jose." San Jose Mercury News. 21 June 2002.

- ↑ Sommer, T. and others, "California's Yolo Bypass: Evidence that flood control can be compatible with fisheries, wetlands, wildlife, and agriculture," Fisheries 26, no. 8 (2001), http://web.archive.org/web/20021019103634/http://www.fisheries.org:80/fisheries/F0108/F0801p6-16.PDF (5 July 2002).