About Me[edit | edit source]

My name is Meghan Heintz, I'm currently studying environmental resource engineering at Cal Poly Humboldt. I choose this career path after meeting dozens of environmental refugees while spending my junior year of high school in Quito, Ecuador. My long term goal is to work in part as a wastewater or bioremediation engineer and in part as a cultural and language liaison on environmental projects in Latin America.

Background[edit | edit source]

The summer of 2010, I fell completely and madly in love with Chiapas, Mexico during my participation in HSU's appropriate technology program. My particular project,HSU Chiapas micro hydro feasibility study, did not provide me with as much community interaction as I was hoping for. Therefore, I was extremely excited to be asked to return to Mexico as a grader the summer of 2011 and participate in more community based projects. However, due to violence in Northern Mexico, our appropriate technology program had to be moved to the Dominican Republic. I'll admit I was disappointed in the location change but only until I saw the beautiful white sand beaches surrounding Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic.

First impressions[edit | edit source]

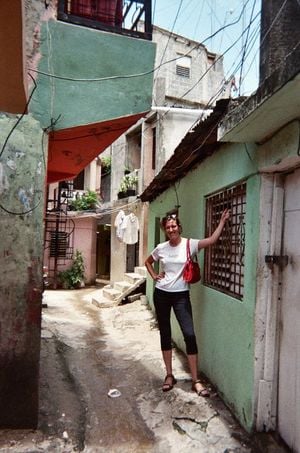

The Dominican Republic is a stunning country, not just the landscape but also the people. I have never been so lucky to have lived among such beautiful and open people before. It must be the Caribbean air or something because as a whole this is friendliest country I've ever visited.

Selecting projects[edit | edit source]

-

Getting the kids involved in the project selection process

-

Aerial view of project discussion meeting in the Yuca

This is a anecdote paraphrased from Lonny Grafman I personally found to be very accurate in terms of describing the failures of many NGOs, if you give a community a thousand shoes sure, the kids won't be barefoot until they grow out of those shoes but then you've put the community shoemaker out of business. Coming to a community and participating in a one way exchange of material goods is not nearly as beneficial as a learning experience between your group and the community. To have a successful project the needs and resources of the community must be assessed. This can't be done effectively without sufficient community engagement.

This program accomplished this feat by starting out with small meetings with community leaders and a few members from the program and slowing increasing the numbers of participants. This way the community is not overwhelmed with the number of outsiders. By the time we held out large meeting with all our students the community was ready to engage with us. From the aerial shots of the meetings there was no distinguishable leader of the meeting. Instead of some gringos lecturing at the Dominicans a genuine discussion and exchange of ideas was taking place. We discussed and listed the problems and the resources of the community in sharpie and large pads of paper. For me the most exciting part of this was when one of the Dominican women pointed out how much longer the resources list was than the problems list.

The next meeting we discussed the proposed projects, alternative construction, wind power and rainwater catchment, and community members joined in discussions on the project which they had the most interest in. The alternative construction project was selected based on the communities need for a new classroom for the primary school. The wind power project was chosen to supplement energy consumption from the unstable and unpredictable central grid. The rainwater catchment project was borne from the need for potable water.

Developing working relationships[edit | edit source]

Once the projects were selected, we had to create stronger relationships with our community partners to implement these projects. The American students had to foster close working relationships with their Dominican university partners. The cultural understanding and knowledge of local resources was an invaluable addition by the Dominican university student. Then, our teams had to engage the interest and support of the members of the Yuca community. For me, working with the Yuca community members was the most beneficial part of this program. Many of our projects required skills the average American college student lacks. My first attempts to mix cement and swing a pick ax into a pile of rocks were laughable. After a little bit of chuckling, our partners set me straight and I starting working more effectively. I found this type of physical work to be very empowering. Another community member showed me some welding techniques. This really intrigued me and now I'm starting to take welding courses at my local community college. At the end of this program it became very clear to me that the most valuable thing I had built in this community was friendships rather than projects.

Lessons learned[edit | edit source]

At this point, I would like to discuss the take home messages from the outcomes of each project. The rainwater catchment project benefited from the expertise of my friends at Isla Urbana, a group that builds urban rainwater catchment systems in Mexico City. An important factor in every project I've ever participated in has been sourcing help from people who have worked on similar projects. I strongly recommend searching extensively for similar projects and then emailing a relevant question to someone involved in that project. You may be surprised how excited someone is to advise you on your project. Many mistakes can be avoided by sourcing advice this way. This project also benefited from abundant community interest. The bottom line is if the community isn't interested you need to go back to the drawing board and find a project the community can get behind. The factor that nearly derailed this project was