Bee-keeping is now admitted, both in this country and in Europe. to be one of the most profitable rural pursuits. Perhaps in no other branch can so large and sure profit be secured in proportion to the capital and labor necessary to be invested. One hundred to five hundred per cent, has often been realized in a single season, where intelligent care has been given these little insects; and there

are instances recorded of even greater returns from them in unusually good seasons. This business is made by many intelligent persons a specialty, but it is not necessary that This should be the case, indeed until the honey resources of the United States are better developed, it is important that all classes should be made acquainted with the facts. the farmer may, by devoting a little spare time to a few colonies of bees, secure an abundance of a choice luxury for his table, or for sale. The merchant and professional man, who has but little time and little land, may secure a pleasant relaxation from his cares, by tending a few hives, while the laboring man, or the mechanic, may keep a few colonies in his yard or garden, and be repaid a hundred-fold for the care be gives them. Nor is the occupation suitable for men alone, since women can give bees all the care they need, and many who have tried bee-keeping as a channel for their industry are reaping rich rewards. Neither is it necessary that bees should be kept in the country to thrive, for in all our large towns and cities a few colonies are found to do well, since the bees are not confined to the brick walls, within which their hives stand, but seek the suburbs and gather sweets which abound there. In nearly every part of the United States, bees will thrive where man can live. It has been proved that in all localities where there is arable land, or woods, or wild prairie bees gather their own stores and a surplus for their owner, and that no part of our land is likely to be overstocked, but, on the contrary, bees may in most localities be increased ten fold, and the many gather as much honey to each hive as the few now do.

Therefore we would be glad to see men and women, in all situations in life, in town, city, and country, giving to bees intelligent care.

Brief Natural History of bees[edit | edit source]

Every one keeping bees should be well informed regarding their natural history, as their successful management must be based on their instincts and habits. Works on the subject abound, and it does not come within the limits of this article to do more than glance at the internal economy of the hive.

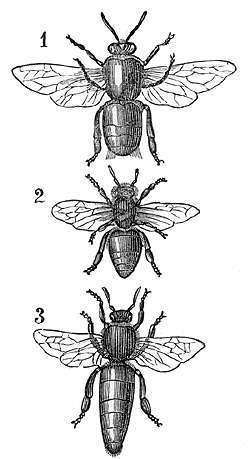

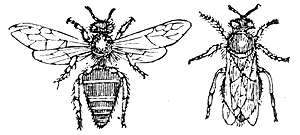

Its inmates are of three kinds. One Queen, who is the only perfect female who deposits all the eggs from which the other bees are produced. These eggs are of two kinds: the one develops into the drones, who are the male bees, and the other, under ordinary treatment, produces the worker bees, who are imperfectly developed females; but the same eggs will, under different treatment and care produce perfect females or queens. As but one queen is allowed in any hive at one time, these young queens are only reared when a colony is deprived of a queen, or when swarming season makes it necessary to provide queens for other colonies. In from three to five days after birth, the queen leaves the hive for fertilization by the drone or male bee. Before this impregnation she is capable of laying the eggs which produce drones, but no others; after that she can produce either kind. Except for this purpose, she never leaves the hive, unless when she goes with a swarm, and one impregnation is operative for life. She lives on an average about three years. The workers have but a brief existence, not three months long on an average; and the drones are reared only in spring when swarming season approaches, -and after serving their brief purpose dissapear. The worker bees are the laborers: they cleanse the hive, feed the young bees, provide for the queen, defend their home from all invaders, and gather all the stores; the drones being consumers only.

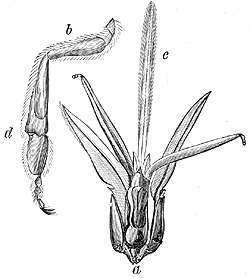

They gather honey, which is a secretion in many flowers, pollen, the farina of various plants, and which is largely used in forming bee-bread, and also propolis or bee glue, a resinous substance which is used in fastening the combs to the sides of hives, and to fill cracks or open places.

Wax is not gathered, as many suppose, but is an animal secretion as truly as lard or tallow. The bees fill themselves with honey and hang quietly in clusters until scales of the wax appear upon their abdomens, which scales are dislodged and formed into the cells. These cells have been one of the wonders of nature, and a theme for the poet in all ages - since nothing can exceed their beauty and mathematical accuracy.

It is estimated, and proved by careful expert meets, that from 20 to 30 lbs. of honey are consumed by the bees in the secretion of one lb. of wax; hence it is very important that all good pieces of comb should be saved and given again to the bees.

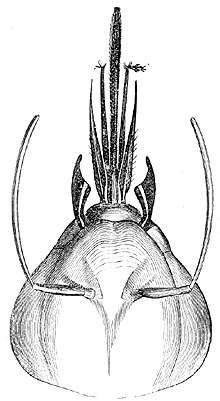

An egg is deposited by the queen in a cell prepared by the workers; in three days it hatches into a small worm, is fed and cherished until about the eighth day the larvae becomes a nymph and is sealed up in its cell to emerge, a perfect bee. The drones mature in 24, the workers in 21, and the queen in from 14 to 17 days from the egg. Of Hives.

A great revolution has been effected in bee culture since it has been found possible so to construct hives that every comb will be built and secured by the bees to a movable frame, so that each one or all can be taken out and examined when occasion requires, without danger of stings to the owner or detriment to the bees. These frames have laid open all the internal economy of the bee-hive, and an intelligent use of them can hardly fail to secure success. They make certain, what was before guess-work. With them in use, the bee-keeper may know at all times the exact state of his bees and the amount of their stores; if they are weak, he can strengthen them by a comb of brood or honey from some other hive; if they are queenless, he can supply a new queen, and in the fall he can unite any two poor ones and make of then a good stock colony. A colony of bees in a movable comb-hive need never grow old, it is a ”perpetual institution.” Though these frames have long been used in Europe, to Rev. L. L. Langstroth belongs the honor of introducing them first in a simple practical form into the United States, and since then they have been made and used in many different shapes. Some of these hives, with the valuable principle really belonging to Mr. Langstroth, combine many features not only useless but absolutely injurious to the bees; and others are a decided improvement on the form and arrangement of the original patent. Among them, the American improved movable comb hive is found to be most simple and easy of construction and the safest of all forms for a winter hive. The time is gone by when a bee-keeper can succeed in making his stock profitable in hollow logs, boxes, or even straw hives, as they afford too many hidingplaces for the moth and its progeny of worms. As well might a farmer hope for success if he used old-fashioned ploughs, sickles and other farming implements. A good plain, well-painted hive will last a lifetime, and such the bees require. Any extra ornament or expense may be added at pleasure, but they will gratify the tastes of the owner rather than aid the bees. Ample room should be given on all hives for boxes to contain surplus honey. They naturally store their choice honey as near the top as possible; and when boxes are on there, in the season of honey gathering, pure honey, unmixed with beebread, will be put in them. Boxes for this purpose are made of various forms and sizes: when their contents are intended for market, they should be made to bold about six pounds, and have one glass side, as in that form honey is most salable. For family use, boxes containing from 12 to 20 pounds are better.

These surplus boxes, as they are called, should not be put on the hives until fruit-blossoms abound. Early in the spring they would not be used by the bees, who are then rearing brood as fast as possible, and as they would allow the heat of the hive to escape, they would prove injurious. After the bees begin to store in them, they should be closely watched, and, when full, changed at once for empty ones, - as bees are often idle unwillingly, because they have not room.

Subduing Bees.

The stings of bees were given them for the protection of their stores. They are not disposed to sting when not in danger, and every bee who does sting dies. Away from their own hive they rarely make an attack. The natural dread of stings deter many from keeping bees, who would be glad to do so. In the use of modern hives, the danger of being stung is much lessened, as they give you facilities for subduing them. A bee with its honey sac full never stings. When you alarm a colony of bees, they all instinctively at once fill their sacs with honey, and after time has been allowed them to do this, their hive can be opened and examined with no danger from their anger. When any operation is to be performed, a little smoke from decayed wood, or a bundle of burning rags, should be blown in among them, when they at once proceed to fill themselves with honey, and in a few moments they will all be peaceably inclined. Another way is to open the hive at the top and shower the bees with sweetened water. They immediately fill their sacs with it, and are so subdued that no angry note will be heard from them. Many beekeepers now go among their bees, every hour of the day, for a whole season, without receiving a sting. A fearless manner no doubt has something to do with this; and in order to secure it, all beginners until they lose their fear are advised to wear a tree-dress. This may be cheaply made of a piece of wire cloth, large enough to cover the head and face, with leather sewed into the top for a crown, and a muslin curtain, half a yard deep, all around the bottom. The hands may be effectually protected by india rubber gloves with gauntlets, or a pair of woollen mittens, knit with one finger as for soldiers. These dipped into cold water before using, answers good purpose. This dress is only needed until you have learned how to manage your bees: after that, one no more fears their sting than he does the kick of a favorite horse or cow. If one is stung, a little common soda or saleratus, which is always at hand, moistened and applied to the part, will neutralize the poison injected by the sting and at once relieve the pain.

Enemies of Bees[edit | edit source]

Before the newlight which in the past few years has been shed upon the subject, bee-keeping had become a very precarious pursuit. Bees were supposed to have many enemies. The moth or miller, with its progeny of worms, had become very numerous and destructive, and did much mischief. In all parts of the country many bees were lost in wintering, so that the annual increase by swarming did not make up for the number lost in various ways. In some regions the product of wax and honey was yearly decreasing. It is now well known that, under a right system of management, a colony of bees has no enemies that it cannot overcome, and can be made every year, whatever the season, to give a good return in honey or swarms to its owner, and in most seasons will give both. The secret of all successful management is to keep your colonies always strong, and they will protect themselves; and the use of hives giving you the control of every comb, enables you always to secure this end. When he possesses this power, the moth has no terrors for the intelligent bee-keeper since a strong stock is never injured by it; and severe winters are of no consequence, for bees can be properly protected to withstand them. In some seasons much greater profit may be realized than in others, but some may be expected in all.

The Italian Bee[edit | edit source]

Which has been for years well known in Europe, has been successfully introduced into many parts of Europe, and is rapidly taking the place of the old species or black bee. At first it was regarded with suspicion, but its good qualities are now conceded by all who have tried both varieties under the same circumstances. It is similar in form and size to the black bee, but distinct in color, being of a golden hue, and also has three distinct golden rings below the wings about the abdomen.

It is found to be more active than the other bee, making three flights where it makes two; it also is more hardy, working earlier and later, and in cooler weather. Its bill is longer, so that it gathers honey from plants which are not frequented by the common bees. Its queens are more prolific, so that they may be increased much faster with safety. Careful experiments have decided that one colony of Italians will store more honey then two colonies of native bees, and at the same time give more swarms; while some years, when the native bees do nothing, Italians gather large supplies.

The general introduction of this bee into every part of our country is greatly to be desired.

How to change Colonies of Black Bees to Italians. Since the queen is the mother of all the bees in the hive, and deposits all the eggs, it follows that they will all be like her. If then the queen be taken from a colony of common bees, and an Italian queen be put there in her stead, all the eggs thenceforth laid will produce Italian bees, and as the life of the worker bee is short, in from two to three months the old bees will all have died out and be replaced in greater numbers by the beautiful Italians. These Italian queens are now reared for sale by scientific apiarians, and sent to any part of the world with perfect safety. If a pure queen purely impregnated is purchased and introduced to any colony of black bees, an Italian stock is secured in the best and least expensive way. Italian queens impregnated by common drones will produce what is called ”hybrid” stock, and though this is a great improvement on the black bees, it is very desirable to secure a queen to commence with that is warranted pure by some reliable person.

Many bee-keepers have, by the purchase of one queen, succeeded in Italianizing all their stocks to their great profit and pleasure.

How to introduce an Italian Queen to a Native Colony in the Safest Way[edit | edit source]

A colony have a great attachment for their queen being, it would seem, conscious that on her presence their whole existence depends. When she is taken from them, some precautions are necessary, lest they destroy a strange queen presented to them. There are various ways of doing this, but the following will be found safe and easy. Take away the queen of the colony to which the Italian is to be given. To find her most easily, open the stand in the middle of a fine day, when many bees are absent from the hive. Disturb the bees as little as possible, and have an assistant to look on one side of the frame, while you examine the other. Look first on the combs near where the bees cluster, as the queen is apt to be there. As soon as you have found and killed her, put the Italian queen, with three or more of the bees that come with her, into a wire cage which always accompanies her when sent, and lay this over the frames near the cluster, or, if the weather be cool, the cage may be laid between two frames. Leave her there forty eight hours, and then, without disturbing the bees withdraw the stopper and allow the queen to go into the hive at her pleasure. Open the box in which the queen is sent in a light room, that, if the queen fly, she may be caught on the window. Never handle a queen by the abdomen, as a pressure there may be fatal; take her by the upper part of the body or wings.

Move the hive to which you wish to introduce the queen to a new position some distance away. Then take from it two or three frames of comb containing brood and honey, shake all the bees from them, put them in an empty hive, and place this hive where the other stood; close all the entrances except one hole in the top, and through this gently put the new queen on to the frames and shut her in, then open entrance for one bee at a time in front, and allow the bees that are out in the fields to come in. Being full of honey, and disturbed also at the new appearance of their home, they will not harm the stranger queen.

If it is the right season of the year for making new colonies, you may, towards night, add a frame or two more of brood from some other colony, and as a majority of the worker trees from the removed colony will return to their new location, you will have a good, new, properous colony. The one you have moved will also do well and soon be as strong as ever, for it retains the fertile queen. If you do not care thus to divide, look over the removed hive at once and kill its queen. Leave it an hour or two, and then take all the remaining frames, shake the bees from them and place them in the hive where your Italian queen is, and just at dusk put all the remaining bees in the old hive, in front of the new, which they will gladly enter. In this way you remove by degrees all parts of a colony to a new hive, except its queen, which you replace by the Italian. This is my favorite way of exchanging queens.

Swarming[edit | edit source]

Bees increase the number of their colonies by swarming. In early spring, if all be right with then, numbers of young bees are reared until the hive becomes crowded. Then drones are reared, and queen cells are built, in which eggs, from which workers are usually reared, are deposited, and by different feeding and care, are transformed into young queens. When these queen cells are capped over, some fine day, the old queen and a part of the bees leave the hive to seek a new habitation. The hive, however, is left full of brood which is hourly hatching, and soon becomes as populous as ever. A young queen hatches in about eight days after the old one leaves, and, if she is permitted, will destroy all the other embryo queens. If the bees, will to swarm again, they prevent her from doing this, and then second, third, and often more swarms come out, led by these young queens. One of the evils attending natural swarming was the uncertainty attending it. In some years, bees did not swarm at all, and no increase was secured; in others they swarmed so frequently that all were small, and poor, and the parent hive was left so weak as to be worthless. Many of these swarms too left their owner for the woods, in spite of watching and care to prevent it. It is now found that bees can be controlled perfectly in this matter, divided as much as the owner finds desirable, or swarming prevented entirely if he so desires.

This plan of artificial swarming very much simpli-fies bee-keeping, as it saves long tedious watching, and also enables one to choose his own time and divide his colonies at his leisure. It is best every year to secure a moderate increase; this may be done and still quite as much honey obtained as if no swarms were taken. But if many swarms are allowed to come or are taken, but little if any surplus honey will he obtained: Young bees are nourished and fed with honey, and much is consumed for their use, and it would be as reasonable to expect hens to afford eggs and chickens at the same time, as to look for surplus honey, when all the force of the colony is engaged in rearing bees for new swarms.

Time and Manner of Making Artificial Swarms[edit | edit source]

When drones appear, any strong colony may be divided with safety. It is necessary, however, to choose a time when honey is abundant in the fields - and also when the nights are warm. After one has a few colonies in movable comb hives, dividing them is a very simple matter. Have a hive at hand of the same size and pattern as your others. Then from four hives take each two frames and place them in the new hive, supplying their place in the old with empty frames. Then move a hive which you have not disturbed, a rod or more away to a new place, and place the new hive where that one stood. This should be done in the middle of a fine day, when many bees are absent in the fields. These will come in loaded to their old place, and find it strange;; and as it contains stores and young bees hatching, and eggs from which to rear another queen, they will at once proceed to rear one and remain and work as contented as ever.

This process may be repeated every two weeks until you have secured sufficient increase. The hives from which you take the combs, and the ones which you move to a new place, will lose so many bees that they will not think of swarming, but will energetically make up their loss and be better than if nothing had been taken from them. This is the safest of all ways to divide bees, and can be safely practiced by beginners.

As they acquire practice and confidence, other ways will suggest themselves. The trouble generally is, that the novice, finding he can multiply his stocks so easily, does it to excess, and by so doing cripples the strength of all. However many eggs a queen may be able to deposit, her laying is always found to be in proportion to the strength of her colony, and thus the number of bees may be increasing faster from one queen in a good strong colony than from two or three in those that are weak in stores.

A bee-keeper is rich, not in proportion to the number but the strength of his hives.

How to change Bees without Loss from Common to Movable Frame Hives[edit | edit source]

The best time to do this is about the season of swarming, which season varies with the latitude and climate. In the Northern States, June is the month of swarms, in the Middle and Southern States they come with early and abundant bloom.

About the time when swarms are expected naturally, take the hive which you wish to transfer, and blowing a little smoke into the entrance, remove it a rod or more from its stand, leaving an empty box or hive in its place, into which the bees that are out in the fields may gather. Invert the hive which you have moved, and put over it an empty box or hive, as near the same size and shape as possible, and stop all holes or cracks between the two with grass or weeds that may be at hand, leaving no hole large enough for a bee to escape. Then with sticks keep up a sharp drumming on the bottom hive, at which the bees, alarmed, will fill their sacs with honey and mount into the upper hive. In from twenty to thirty minutes most of the bees with their queen will be in the empty box on top. The beginner need not fear driving too many; let all go that will. Then carefully set the box containing the bees in a shady place, and take the old hive back to the place where it stood. While you have been driving, many bees will have come back to their home, and finding it gone, will be roaming in and out of the empty hive in distress. These will at once rush into the old hive when it returns, and gladly adhere to it. Then remove it to a location some yards off, when, as it contains many hatching bees and eggs, the bees will at once rear a new queen to replace the one just driven out, and in a short time be as prosperous as ever. Now place your new movable comb-hive, with its entrances all open, on the old stand, and spread a sheet before it, on this sheet empty the bees you have driven into the box, and they will at once take up a line of march for the entrance of the new hive; if they gather there, brush a few in with a wing or twig, and they will call the others, who enter in a body and accept the new hive as their home.

You have now a nice swarm in your new hive, which will work as well as any natural swarm and quickly stock their hive. You have besides your old hive, in which the bees are rapidly hatching and in three weeks they will have a young queen and a goodly number of bees, but no brood in the combs. Therefore in three weeks repeat the process of driving out the bees, and after this is done split open the old hive, or carefully take off the side, and fasten all straight nice pieces of the comb into the frames of a movable comb-hive; a little melted rosin will help hold them in place. Comb need not be rejected because it is old or black, as, if it is straight and free from mould, it is quite as good to rear bees in or store honey for their use; indeed, it is proved that old comb is better than new for these purposes. No dronecomb should be put in the frames. This may be known by the larger size of its cells. Arrange the frames containing comb in the hive, set it in its place, and empty the bees on a sheet in front, as before described. They will soon securely fasten the combs, and work on all the better for this necessary disturbance.

To the novice it may seem incredible that bees should be thus driven from hive to hive and directed as you please, but it is done now every day through the summer, by hundreds of beekeepers who find not only that it may be done without loss but to great profit. After bees are once in movable comb hives, little change need be made when all is well with them; their great advantage consists in the power they give their owner to discover when any thing is wrong, and apply the remedy, - as also the facility they afford for taking surplus honey from the bees in nice shape without trouble.

Storing Honey in Boxes[edit | edit source]

In spring and early summer, however much honey bees may gather, they do not store it for future use; seeming instinctively to know that supplies will then come from day to day. At this season most of the stores that they gather are consumed in the rearing of brood. After swarming time they gradually decrease the broodrearing, and then their instincts prompt them to gather industriously supplies for winter. If advantage be taken of this instinct by their owners in all ordinary seasons, a surplus of choice honey may be obtained. It is not uncommon for experienced bee-keepers to secure an average of 100 lbs. from a number of colonies, - and yields of 160 lbs., and sometimes more, have been taken from single ones. This is independent of the necessary honey which must be left with the bees for winter, and it is not taken in the old barbarous way, by killing the busy workers. Hives are so arranged that as the bees choose to store their purest honey near the top of the hives, here the boxes are put in which it is desired to have them store it.

Nothing is gained by putting on these ”supers,” as they are called, too early. In cool spring weather they are injurious, for they allow the heat to escape from the main chamber, which at that season is necessary to develop the brood. They may be placed on usually about the time that fruit-trees blossom. Hives should be so arranged that, when one set of boxes is partially filled, they may be raised up and another placed below them, and then the bees extend their combs into these new ones, and work in both at once. They are often known, in the height of the gathering season, to be storing in 16 boxes at once, each box containing, when full,, 6 lbs. As one of these boxes is filled, it is removed quietly and an empty one slipped into its place. If the full one is carried away from the hive, or into a dark cellar and left for a time bottom upwards, the bees will all leave it and return to the hive, and a piece of cloth or paper can be pasted over the entrance to the box, when it may be kept any length of time. A box is more easily examined when one side at least is made of glass; the honey also looks nicer when offered for sale. It is thought less honey is stored in them, if partly of glass, than when made wholly of wood, and also that bees work more readily in boxes made large, so that one shall take the place of four on a hive. For market, however, the small glass boxes are always best. If small pieces of honey-comb, clean and fresh, are fattened in the boxes with a little melted wax and rosin, the bees commence more readily in them, - they seem to like a ”start in life.” Boxes that are only partially filled, when frost puts an end to the gathering season, should be taken off and carefully preserved for another year, when the bees will complete them.

Value of Comb[edit | edit source]

In old-fashioned bee-keeping, when bees were killed by the fumes of sulphur, that their stores might be appropriated, wax was regarded as of little value. It was not supposed that bees would use it again, and the idea that old comb would be given to new colonies was never suggested. Now since it is known that every pound of wax is worth to the bees at least twenty pounds of honey, because so much must be consumed in its production it is evident that economy would prompt that every pound should be made available. By the use of movable comb-frames every piece can be fastened in and given to the bees, who gladly receive it. When a bee keeper has a quantity of comb made in frames, he can make them of great value to him. Such combs should be carefully preserved, if there is a surplus of them, from year to year. Comb never seems too old for the bees to use: instances are frequent where bees have been kept 12 and 15 years in hives stocked with comb which has never been removed. Even boxhives from which the trees have died, may be kept with care, and a swarm put into them the next year.

I once had two swarms of bees come off the same day, one of which was put into a hive stocked with comb, and the other into an empty one. Both swarms seemed of the same size. The one put into the hive with combs gave me that year forty-seven lbs. of honey in boxes, while the one in the empty hive barely filled up for winter. Many facts of the kind might be given to prove that it never pays to melt good worker-comb at ordinary prices of wax and honey.

A machine is about being introduced into this country by which the combs can be emptied of their honey, and then returned to the bees to be refilled, which will enable them to gather more when honey is abundant.

Bee Palaces, or Non-Swarming Hives[edit | edit source]

Attempts have been made at various times to keep bees in small closets in chambers of a house and in a palace or large hive built for the purpose with a view to obtaining large yields of honey from them and allowing no increase. All such rooms are constructed upon wrong ideas of the habits and wants of the bee. Experiments without number show that 2200 square inches is ample room for any queen; giving her space to deposit all the eggs she will, and room enough to contain necessary stores for the colony, and that beyond that, the room for honey should be in a separate apartment, where it will be free from bee bread and impurity. A queen will deposit no more eggs in a room six feet square and eight high (as they are often made) than she would in an ordinary hive. If a number of swarms are put in to stock it, as is the custom, only one queen will be retained, and though a large amount of honey may be stored at first while these bees live, in one season they will all be gone, only to be replaced by the progeny of one mother like smaller hives. It is difficult also to determine, in such rooms, how much honey must be left for the bees; and in such palaces they do not winter well. They do not often swarm when thus kept, and this is the great objection to the plan. By swarming, the queens are exchanged for younger ones, and thus the colony is kept vigorous. Swarming seems to be ”nature’s way” of providing for the increase of bees and the renewal of queens, and in nothing can we go counter to the instinct of any creature without loss.

This is also a very expensive way of obtaining honey, as figures will show. Suppose a man to obtain from his bee palace an average of one hundred pounds a year for ten years, which would be doing better than they were ever known to do in such a situation, this would be worth at a fair average price for honey, 20 cts. per lb., or $200.00. Suppose the same swarm put into a good hive and allowed to swarm every year, which bees may safely do, the increase in ten years would make his number five hundred and twelve colonies, which at $5.00, an average price for bees in this country, would be worth $2560.00. In this calculation no allowance is made for the honey which would be taken in the meantime from all these bees.

Bee Pasturage[edit | edit source]

The principal sources from which bees obtain honey, are the blossoms of fruit-trees, and small fruits, white clover, linden or bass wood, and buckwheat. Where all these abound, bees will thrive in great numbers, and where any two of them are abundant, many will prosper. Besides these, many minor sources are found, from the time the willows and elms blossom in the spring, until frost kills all bloom in the autumn. There are few parts of the United States where it is necessary to raise crops specially for their honey-producing qualities, though crops which produce honey, such us clover and buckwheat, are more valuable on that amount. A new species of clover, the Alsike or Swedish white clover, is being introduced into many parts of the country, and is found

highly valuable both as a forage and honey crop. It is hardly possible to overstock a section of country with bees. It is not the same with their supplies as with pasturage for cattle and sheep, which when eaten off requires time for a new growth. The nectaries of honey producing plants, when filled with honey, are emptied by the bee, and while it goes with its load to the hive, the secretion goes on anew, and by the time the bee returns, the tiny cup is full again. The whole art of bee-keeping consists in so managing colonies that all may be strong in numbers when honey is abundant - for a hundred large strong hives will rapidly fill up in the same time and place where a weak one will barely live. Every beekeeper should understand the resources of the section of country where be lives and if he does may aid his bees by sowing buckwheat that will bloom at a time when other pasturage for them is scanty. Borage is highly esteemed as a honey crop, and it is undoubtedly more valuable than weeds which produce no honey, - and that I consider faint praise.

Feeding Bees[edit | edit source]

There are few times when it will be found profitable to feed bees, - the right way is to keep them so strong that they never will need feeding. As it is hardly possible for a beginner to do this always at first, it may be well to know that the best substitute for honey in feeding bees is plain sugar candy. A few pounds of it, thrust down between the combs in the spring, will often save a colony from starvation. If honey is fed to them, it is apt to attract robbers from other hives. Where movable comb-frames are used, a comb of stores may be taken from a strong colony that can spare it, and

given to a destitute one, and that be saved while the other is not injured.

In the spring, rye meal may be fed to all bees with great advantage. It supplies the place of the farina of flowers, and is eagerly gathered by them. It may be placed in shallow pans or troughs, near the bees, and they will gather about it in great numbers. Large apiaries have often consumed a hundred pounds of this meal in a single day. Wheat meal is taken by them, but rye is preferred. When the earliest blossoms appear, and they can gather pollen from natural sources, they take the meal no longer. Bees use much water, and an apiary should be, if possible, located near some small running brook or stream. It is said, bees in the woods are never found many yards distant from running water. If they are not so situated, water should be set for their use in shallow vessels, with shavings, or leaves, or moss, for floats.

Wintering Bees[edit | edit source]

Because many bees die every winter, it has been thought that keeping them was a precarious business. It has been said that bees being natives of warm climates, could not withstand cold. To winter bees successfully, has therefore been deemed a difficult matter, but the only trouble is that the laws which governed them were not understood. A solitary bee is easily chilled by even moderate cold, but by clustering in large numbers together their animal heat is maintained. When winter comes, they cluster compactly together, and remain until warmer weather in a semi-torpid state. If in the coldest day in winter a thermometer be thrust into this cluster, the mercury will rise to summer heat. To winter bees successfully in the coldest winters, only three things are necessary: ventilation in the right place, plenty of food where they can reach it, and sufficient bees in number to maintain the requisite animal heat. In hives where these conditions are secured to them, they winter in perfect safety in any climate, in the North even better than the South, because when warm days tempt them out, many are lost, while, if the weather be settled cold, they are semi-torpid, and consume little, while none are lost by untimely flights.

In the shallow form of hive, bees cannot cluster in such a shape that their stores will be above them, and where they can be kept warm by the heat ascending from the cluster. Such hives should always be kept in a cellar, and abundant upward ventilation given them there. It pays to winter bees in any kind of hive in a cellar, for experiments have proved that they consume much less honey when so wintered. A hive weighing 60 lbs. in the fall of 1863, wintered out of doors, weighed only 15 lbs. the 1st of April; while 20 kept in the cellar the same three months, lost on an average only five lbs. each. Again, six hives wintered out of doors lost an average of 29 1/2 lbs. in weight, each in three months, while twenty in the cellar, the same length of time, lost an average of only 5 3/4 lbs. Experiments like these show clearly that it is best to keep bees warm in winter. If, however, it is not possible to put bees in a cellar, the hive should be of the upright form, of which the American is the best. At least 30 lbs. of honey must be allowed to the bees; and then, if the honey boxes under the cap are removed so that they will have upward ventilation, and the entrances in front are closed securely against mice, they may be safely left upon their summer stands. Hives so left are better to face towards the North, for the sun does not then shine directly on the entrance, tempting them out in weather too cold for them to fly safely.

When bees are wintered in a cellar, they should not be put there until cold weather comes in earnest. That time is usually about the last of November in the Northern States; in the Middle and Southern States, if bees are housed at all, it should be from the time bloom ceases until it comes again. Bees in the North are kept in cellars from three to five months. A warm pleasant day should be chosen to put them out again, for they will be attracted by the light and fly out, when, if it be chilly some will perish. Hives should be heavy when set out in the spring. The time of year when bees consume the largest amount of stores, is during the spring months while raising brood fast. The more honey they have on hand in March and April, the faster they will rear young bees, and the more workers will be ready to gather the harvest from fruit blossoms.

To do a season’s work in good shape, a hive should have left at least enough honey to last them until swarming time, when they will repay the generosity with compound interest.

Uniting two or more Colonies of Bees[edit | edit source]

When the utmost care is taken, in every apiary some hives will be found to have too little honey, and others perhaps, though with honey enough, have two few bees for safety. It is wholly unnecessary to kill these bees, as was formerly thought. Two colonies of bees can be united at any time without loss, and to unite one that has too little honey, with one that has less bees in proportion, will save both and make one good stock colony.

It is found that a colony very strong in bees does not consume any more honey than a weaker one. As soon as frost cuts short the season of honey, all hives should be examined, as with movable combs can easily be done, and their exact state determined. To unite two safely, it is only necessary to blow smoke among both so as to alarm them, and induce them to fill their sacs with honey, or to the same end they may both be well sprinkled with sugar and water. In a few moments the combs may be taken from both hives, and the full ones arranged in order in one of them, while those that are empty are reserved for future use. Then the bees from both colonies are brushed together at the entrance, and go in peaceably. One queen will be destroyed, so that if you have any choice between the two, you can find and kill the other. United in this way, all bees may be saved and valuable colonies formed.

Prevention of Drone Rearing[edit | edit source]

One great advantage of movable frames in hives is the ease with which drone rearing is prevented. One who has not examined the matter would be slow to believe how much honey is consumed in rearing those useless inmates. Here bee instinct falls short, and our judgment must be used. When bees live wild, the rearing of drones conduces to the safety of the young queens.

Late in the season, if honey is abundant, and little brood being reared, colonies construct drone comb to enable them to store faster than they can do in worker combs; the next spring they do not of course tear it down and build others, and it being at hand, the queen deposits eggs in it, and drones are reared. Colonies also, while queenless from any cause, invariably build drone comb, if any. Though it is not best to have any hive entirely free from the large comb in which drones are reared, a few inches square of it is sufficient, and if in an apiary of a hundred hives a few are hatched in each one, it is sufficient. Much honey is consumed in rearing drones, they contribute nothing to the stores, and it is easy to see the economy of a hive in which drone raising can be prevented. Much time has been wasted on the construction of traps, which should catch these supernumerary drones and keep them out of the hive, but it is better to prevent their existence. With movable combs, all large comb can be removed from the main hive and fastened in surplus honey-boxes, where it will be used for storing. One fact should always be borne in mind, viz., that colonies with fertile queens do not incline to build any but worker comb; hence these colonies may most safely be placed in empty hives, and the good comb already built be given to swarms containing young queens. Age of Queens.

The prosperity of a colony depends much on the age of the queen it contains. After the second summer, the laying of the queen decreases, and though she may live two seasons more, it is better to replace her with a young one. With these frames this can easily be done.

Best Way to rear Italian Queens[edit | edit source]

If you wish to rear queens on an extensive scale it is best to have one or more small hives to do it in, as it saves the time of a full colony. A pint, or less, of bees will rear as many and as perfect queens as a large swarm. To induce bees to rear queens, it is necessary to have them queenless, and supplied with the means of raising another.

Some use small boxes, such as those in which queens are transported, to rear queens in, but I prefer small hives, -just large enough to contain two frames, of the same size as I use in my large hives.

When wishing to rear queens, take a frame from the hive which contains your pure Italian queen, and be sure that the comb has in it eggs, young larvae, and hatching bees. Put this into a small hive, and with it another frame filled with comb and a supply of honey and beebread. Then move some strong hive, which can spare a few bees, a yard away from its stand, and put your small one then in its place. This should be done at a time when young bees are flying freely, as they are about noon of any bright warm day. many of these young bees will enter the new hive, and finding it supplied with honey and brood, enough will remain and start queen cells. If it is dry weather, a wet sponge should be placed at the entrance, which is all the care they will need for eight or ten days.

About that time it will be necessary to open the hive, and cut out all the cells but one, for when the first queen hatches, the others will surely be destroyed. These surplus cells should be cut out carefully, and may be made useful by inserting them in the brood combs of hives from which the black queens have been taken. They will hatch there as well.

As in swarming, so in rearing queens, certain principles must be borne in mind in order to succeed, but when these are well understood, thoughtful persons can vary the operations as they please, if they do not go contrary to these principles.

1st. The queen rearing or nucleus hive must always be well stocked with young bees, since these are the ones that build cells or work wax in any way.

2d. As these young bees do not at first gather honey or bring water, the little hive should be supplied with these necessaries.

3d. No eggs from any queen but a pure one should be allowed in the small hive, for bees can move eggs from one coil to another.

4th. When you leave a young queen in these small hives until she commences to lay, you should about the time she hatches, give that hive a comb with a little brood in it. Unless this precaution is taken, the whole of the bees may leave the hive with the queen, when she goes out to meet the drones, and so all be lost; but if brood be given them, they will remain in the hive; bees never desert young brood.

If these directions are followed, it will be found very easy and simple to rear queens for any number of colonies.

If these young queens are impregnated by black drones, they will produce only what is called ”hybrid” progeny.

This, for purposes of honey storing, is equally good with the pure Italian stock, but it soon degenerates. To secure pure stock, queens should be reared in early spring, for then Italian drones appear several weeks before black ones are reared, and the young queens are sure to be impregnated by them.

2007 Update[edit | edit source]

Sadly in the 20th century man mistakenly thought Africanized Bees would be an improvement. 26 Queen Bees escaped in 1957 and their descendents are known as Killer Bees. [1]