Phyto-engineering is defined as engineering design focused around the ability to utilize plants and biological systems to accomplish engineering goals.[1]Phyto-engineering is a design concept readily accepted and utilized by the emerging field of Ecological Engineering. In order to better understand the principles incorporated with phyto-engineering methods, a closer look at the concepts and goals of the engineering field that is closely related is investigated. Ecological engineering is “the design of sustainable ecosystems that integrate human society with its natural environment for the benefit of both.”[2]The field of ecological engineering has adopted the following basic concepts which are mirrored by the similar engineering goals associated with phyto-engineering methods:[3]

1. It is based on the self-designing capacity of ecosystems; 2. It relies on system approaches; 3. It conserves non-renewable energy sources; and 4. It supports biological conservation

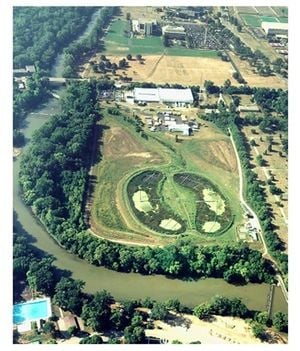

To better illustrate the concept of self-designing capacity of ecosystems, the below figure demonstrates a test conducted at the Olentangy River Wetland Research Park. The two wetlands were designed to have one control, unplanted basin, and one planted with 2500 plants from 12 species. The photo below was taken after six years where both wetland basins have been slowly converging in plant and aquatic uniformity.

Recognizing the large ability and success of nature to self-design is one of the key components of phyto-engineering methods. Engineers are just utilizing the strengths of nature to accomplish engineering goals such as remediating contaminated water. This report will focus on phyto-engineering methods, primarily bioremediation, that have proven to be successful and indicated specifically for use in developing countries.

The suffering resulting from contaminated water is extreme and widespread for the nations of the developing world. Recent studies have developed a direct correlation between the amount of available clean water and the number of deaths attributed to diarrheal diseases. A primary limiting factor for the ability of developing countries to remediate contaminated water is their inability to adopt or afford sufficient technology. It is imperative that developing countries adopt an effective means of remediating contaminated water. The situation surrounding many of the locations in most need of this help requires a tactful, multi-faceted solution. The technique that best fits this description and is most feasible for widespread application in developing countries can be implemented through designs inspired by phyto-engineering. Economic and material costs limit the application of chemical and mechanical engineered solutions. The natural processes associated with phyto-engineering allow for a simple, economical solution. The following sections take a more in-depth look at the methods associated with phyto-engineering.

Bioremediation[edit | edit source]

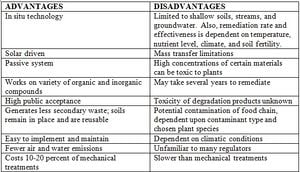

Bioremediation is the use of naturally occurring organisms to return an environment altered by contaminants back to its original condition. Bioremediation includes many processes that can be tailored to remediate different wastewaters employing a wide range of naturally occurring plant and organisms. All of these factors will affect the cost of implementation, materials, and level of technological difficulty. However, the large amount of flexibility presented with adopting a bioremediation practice is also its greatest advantage for use in developing countries. The unstable economic, environmental, and often political situations facing many of these countries requires a level of insight and diplomacy for introducing new technologies and the ability to individually tailor a bioremediation process to the unique circumstances surrounding a location is extremely advantageous in these situations. For this reason a more natural process, bioremediation, is largely considered to be the best option for widespread application in developing countries. Out of eighteen different methods for soil and groundwater remediation, bioremediation appeared to be the simplest and most cost effective method.[5] Bioremediation is effective because it mimics naturally occurring processes in the soil and groundwater and can be easily enhanced by using different techniques and materials for various applications. Specifically, bioremediation is the use of naturally occurring microorganisms like bacteria, fungi, and protist to break down organic materials. Other substances of contamination that can remediated by microorganisms are, “sewage, crude oil, petrol from leaking storage tanks, kerosene, jet fuel, nitrogen from fertilizer, and even small quantities of toxic chemicals such as chlorinated solvents used in heavy industry, pesticides used in agriculture, and creosote used in preserving wood.”[6] The two classifications of bioremediation systems are ex situ and in situ bioremediation. Ex situ technology requires the excavation of contaminants before treatment and is a more costly form of remediation. In situ bioremediation is the use of naturally occurring organisms in the area to remove pollutants at the site of contamination. For this reason, in situ bioremediation systems are recommended for use in developing countries because they are cheaper and can remediate contaminants directly at the site.

Types of In Situ Bioremediation Systems[edit | edit source]

The most recommended methods of in situ bioremediation methods for widespread use in developing countries are discussed below.

Phytoremediation[edit | edit source]

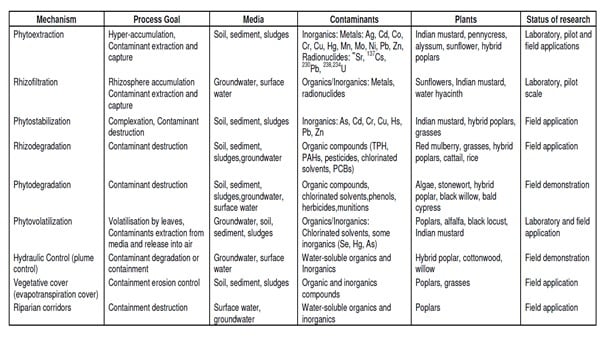

Phytoremediation is the use of plants for a wide variety of environmental improvements. Above ground, plants can help reduce pollution from erosion caused by wind and rain carrying the contaminants away to other sites. Beneath ground, there are several mechanisms that plants are capable of implementing to remediate various contaminants, such as metals, pesticides, explosives, and oil that exist in either soil, water, or sludge.[7] This popular bioremediation technique has high potential for application in developing countries.[8]

Soil Filtration Systems[edit | edit source]

Soil filtration systems, one of the simplest methods of bioremediation, are another promising application for bioremediation in developing countries. The basic process of this method is illustrated below. Soil filtration is one of the simplest methods of bioremediation. This process relies on the ability of microorganisms naturally occurring in the soil to remove any harmful substances from the water. In some cases, like the process illustrated above, different types of vegetation can be incorporated for use in the soil filtration process. Vegetation will be dependent on type of wastewater and plant availability. An added benefit to soil filtration is if grass or another forage material is used for filtration, animals may also graze in this area. The only construction concern of a soil filtration process is locating the system on a slightly inclined field to encourage percolation of the water down the slope through the soil and plants. The wastewater enters at the distribution channel and continues down the slope being filtered by the microorganisms attached to the plants and in the soil. Remediated water is then ready for use at the collection channel. A limiting factor when implementing a soil filtration process is the type of wastewater able to be treated. Not all toxic chemicals are able to be remediated; however, successful remediation of waste water from industries that do not generate toxic material such as food processing centers and animal slaughterhouses is possible. Finally it is important to carefully monitor the pathogen level and correctly implement this process to ensure a limited possibility of disease transmission.

Constructed Wetlands[edit | edit source]

Constructed wetlands (CWs) are another mechanism associated with phyto-engineering processes. CWs are engineered to mimic the natural processes and high primary productivity associated with natural wetlands. Recent studies have promoted their use for developing countries due to their low-cost, low-maintenance requirements combined with the often favorable climatic conditions found in a variety of tropical ecosystems.[11]Constructed wetlands have already been tested and proven to treat a variety of contaminated sites such as municipal, urban, industrial, and agricultural runoff and wastewaters, as well as acid mine drainage.[12]

Design[edit | edit source]

There are six primary considerations to include when designing a particular site.[13] These considerations are dependent on the site condition, phyto-engineering mechanism, and design layout for the remediation system in accordance with the following evaluation parameters:

1. Assessment 2. Remedy selection 3. Design 4. Implementation 5. Operation, maintenance, and monitory 6. Closure

Phyto-engineering methods have proven to be effective through various research studies and have a timeline completely dependent on individual characteristics of the application site ranging from a few months to several years in some cases. Phyto-engineering requires very few materials and a low level of technological capability to implement. The most difficult aspect of phyto-engineering is the selection and monitoring of an effective method because of the variety and flexibility when selecting a method. However, this diversity of phyto-engineering allows for easier adaptation in developing countries. The ability of local community members to be involved in developing an effective method will increase the chance of successful long-term use of the system. Below is a model that can be used to select the appropriate treatment for either industrial effluents or municipal wastewater follow by the process to follow to eco-sustainability utilize the biomass of the wetland plants.[14]

First, researching and analyzing the site to determine what type of bioremediation process is best capable of being successful in terms of location, type of wastewater, and technical support for the receiving region. Once a suitable phyto-engineering process has been decided on, these final considerations must also be carefully considered: the assessment of local governance issues, the cost/benefit analysis for installing and continued operation of the technology, the ability of local management to uphold successful practice of the technology, and the future environmental impact of the resulting technology transfer.

Engineering Theory[edit | edit source]

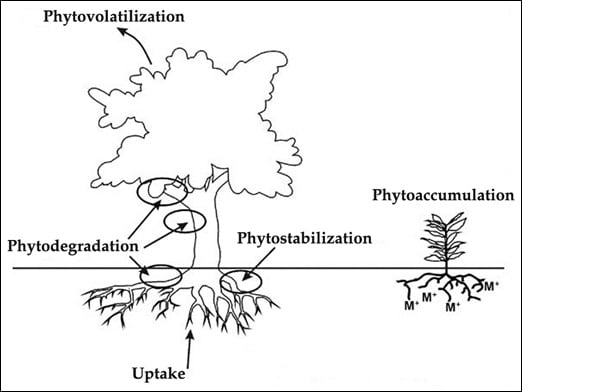

Utilizing the natural processes associated with plant and tree growth, provides multiple benefits to a phyto-engineered system. There are two principal mechanisms associated with bioremediation methods: the chemical and physical improvements within the root zone. Chemically, roots produce an enhanced partial pressure of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) at the root zone due to plant respiration which leads to increased calcite solubility.[16]The physical mechanisms of root penetration into a soil provide multiple benefits to the system. For improved cropping, or vegetative bioremediation, the following improvements are the most noteworthy: increased infiltration at soil-water interface, improved aggregate stability and soil structure, creation of soil macropores, and increased microbial activity.[17]The combined effects of the chemical and physical root mechanisms result in a process of soil reclamation. Choosing crops that can survive in the conditions present at the phyto-engineering site, as well as crop varieties that are capable of remediating any contaminants is essential for a successful phyto-engineering process.The combined effects of the chemical and physical root mechanisms result in a process of soil reclamation. Choosing crops that can survive in the conditions present at the phyto-engineering site, as well as crop varieties that are capable of remediating any contaminants is essential for a successful phyto-engineering process. The several specific features of bioremediation that make it particularly successful in remediating contaminated sites are bacterial size, attachment capability, metabolic diversity, and bacterial lifespan. Since bacteria are such a small size they are able to achieve a close attachment to the contaminant molecules causing them to rapidly biodegrade. Furthermore, as bacteria are usually attached to a fixed location, like biofilm, they are in prime positions to biodegrade passing molecules. Finally, bacteria are self-generating and self-sustaining with an endless range of metabolic diversity with which to biodegrade every major organic contaminant. The flexibility of bioremediation to remediate a variety of substances at differing locations depends solely on the type of bioremediation method adopted. The type of system adopted will also play a large role in determining the ability to accurately measure the quality of water remediated and also the basic timeframe of remediation.[18] Phyto-engineering processes utilize the above scientific principles to accomplish contaminant remediation. The basic processes behind Phytoremediation are illustrated below.

Phytoremediation is effective at remediating groundwater and contaminated soil to the same depth as their roots, making trees more effective than plants because of their longer roots. Phytoremediation can utilize one or a combination of several of the processes illustrated above.

• The process of phytodegradation begins with an uptake of the contaminants into the plant by natural chemical processes. This is followed by the degradation of the toxic molecules into their nontoxic forms. • Phytoextraction is the uptake, or absorption, of contaminants into the plant roots where they are then transported to the leaves and stems for harvesting and disposal. • Phytovolatilization is much the same as phytoextraction except toxic gases are absorbed by the plant roots, transported to the leaves, and then released in the form of nontoxic gases back into the environment. • The process of phytostabilization reduces the migration of contaminants by reducing runoff, surface erosion, and groundwater flow rates through the growth of plants and plant roots.[20]

In accordance with the microbiological and ecological mechanisms discussed above, there are several engineering design principles that must be considered when designing any phyto-engineering system. For constructed wetlands design, the focus is around the correct sizing of a wetland that will allow for the successful remediation of the contaminant.

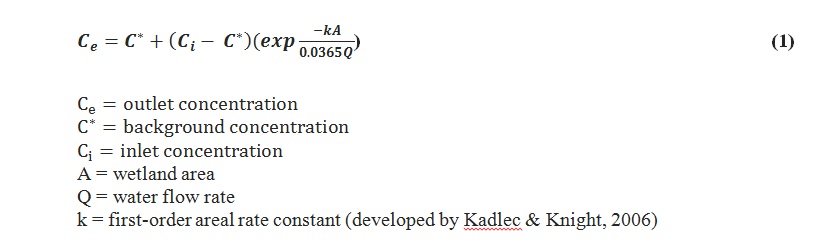

Equation (1) from Arias (2008)[21] is used to estimate the effluent concentration of a unit wetland area. The equation was developed from the k-C* model developed by Kadlec and Knight (2006):[22]

Biodegradation is a critical component of many phyto-engineering processes.Equation (2) below was developed by Buscheck, et al. (1993)[23] along with Equations (3) & (4) to quantify the temporal and spatial analyses for groundwater solvent plumes biodecay rates when in combination with bioremediation at field sites.[24]

Due to the large amount, diversity, and complex construction details of many individual phyto-engineering processes, this report is just meant to provide basic guidelines and persuade the reader to consider these technologies. Fortunately, one of the main principles of ecological engineering and a benefit of phyto-engineering technologies is the concept of self-design. Remember, let nature due to work; and the engineer is just meant to monitor and maximize the potential for success of the system.

Construction[edit | edit source]

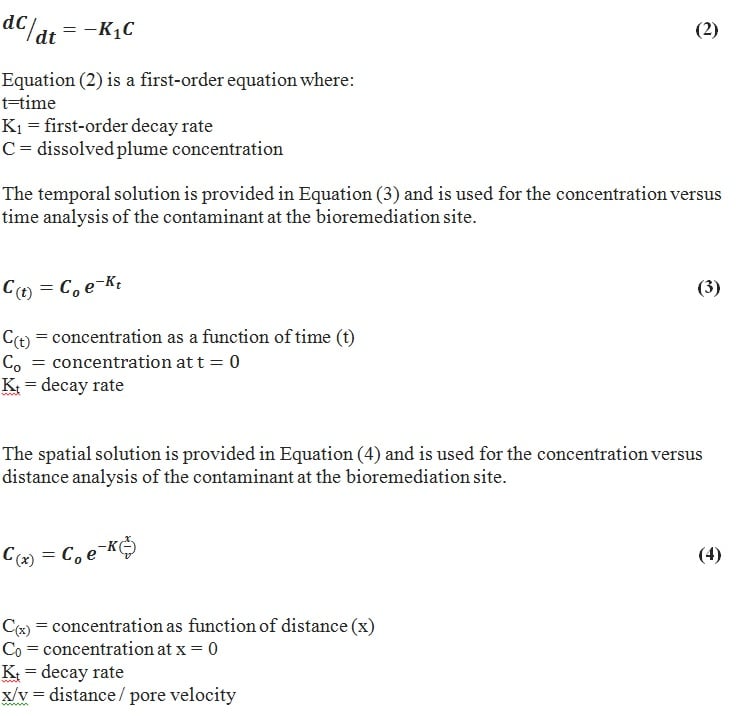

The diverse components of a phyto-engineering system often require more than one expert involved. The following table displays the required skills for the project phases recommended for a phyto-engineered system.[25]

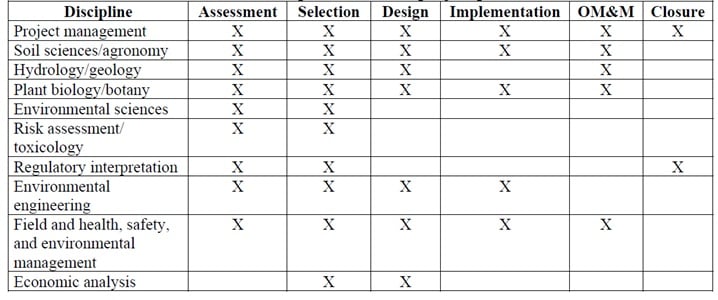

For the design project phase, the following figures display two schematics for constructed wetland design used for treating wastewater. The profile of a Free Water Surface constructed wetland cell which combines emergent aquatic plant, floating plants, and submerged aquatic plants in a shallow wetland that can be either lined or unlined depending on contamination level, environmental regulations, and the performance level of the wetland. The second figure displays a vegetated submerged bed (VSB) or subsurface flow constructed wetland cell. A VCB is unique, and by all ecological definitions, is not an actual wetland as it lacks the hydric soils. Instead, VCBs utilize a gravel media as the foundation of the wetland cell and established plant growth of roots and tubers in to the pore space. VCBs are more appropriate for areas where wetland ecology is not present as it is not reliant on this for successful performance of the system.[27]

Economics[edit | edit source]

Compared to other methods (mechanical and chemical) bioremediation has little overall required materials and a marginal level of technological difficulty. However, this can vary depending on what type of system is chosen to be implemented. In terms of cost, an estimated cost for mechanical technologies, such as soil removing or capping, to be 1 million/ha in US dollars, compared to $60,000-100,000/ha for bioremediation processes.[30] Research conducted by Lewis, Baird, and Burton (2004) estimated the costs of phytoremediation to be 10-20% of the costs required for mechanical treatments. In a bioremediation system, the trees and plants perform most of the work so a lot less material input and resources are required.[31]

Operation and Maintenance[edit | edit source]

The timeline for any phyto-engineered process depends on a combination of several factors. The size and depth of the contaminated site, along with type of environmental conditions present, such as the soil type, will all impact the remediation time. Also, the type and amount of contaminants present will play a large role in determining remediation time. The EPA suggested a general timeline for phyto-engineered processes would range anywhere from a few months up to several years.

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

The ability to monitor the effectiveness of a phyto-engineering system is a struggle because the actual process happens typically without human observation. This means that samples must be taken from the site to evaluate the performance and make sure the quality threshold for safe drinking water is being continually attained. To accurately evaluate the phyto-engineering site several types of consistent evidence need to be documented, especially documentation measuring the biodegradation of the causative agent. This data should be linked to the growth of bacteria at the site, which would prove the success of the process because the bacteria should increase in numbers as the contaminant is degraded to ensure proper functioning of the system.[32]

Impacts[edit | edit source]

The biggest challenge in adopting a phyto-engineering method is successfully tailoring the method used to the environmental conditions present. An ideal situation in the phyto-engineering method of bioremediation requires the contaminant being remediated to be the primary substrate fueling the bacteria’s growth. This requires that the contaminant be one of the required growth substrates for the particular bacteria. The environmental conditions must allow for the microorganisms to grow and multiply in order to degrade the contaminants. Environments with high concentrations of toxic chemicals or salt limit the survival of microorganisms resulting in the inability of the microorganisms to remediate their surroundings.[33]A major advantage of phyto-engineering is the positive influence it has on the surrounding environment while still remediating the site. Phyto-engineering processes usually provide an alternative of either harvesting or grazing the vegetation being used during remediation. This can help offset the cost of the operation while providing high public appeal for the ‘green’ technology.[34] In order to experience a smooth technology transfer and a successful phyto-engineering process, three imperative issues that must be fully addressed.[35] First, provide all relevant information regarding the system, or any technology, so that local community member can make informed decisions involving the development and future continuation of the system. Second, include the local community in the complete decision making process and facilitate full involvement with the process of implementing the system. Phyto-engineering allows a wide variety in choosing a method that allows local communities to develop and improve upon existing designs to ensure the phyto-engineered system is perfectly tailored to local cultural, economic, and environmental conditions. Third, ensure consistent support for the continued successful application of the phyto-engineered system by building capacity on the part of local decision makers to take over system implementation.Phyto-engineering methods resemble processes that naturally occur in the environment. This allows the technology and process behind how and why it works to be more easily grasped by cultures that lack any real knowledge base in the arena of remediating contaminated water. Implementing a natural process such as bioremediation is a much more feasible solution than trying to construct a large mechanical plant because people can intrinsically grasp the process and realize the importance behind the processes of phyto-engineering. Trees and plants are essential for environmental sustainability and are therefore more appealing for use to the general public.

Dissemination[edit | edit source]

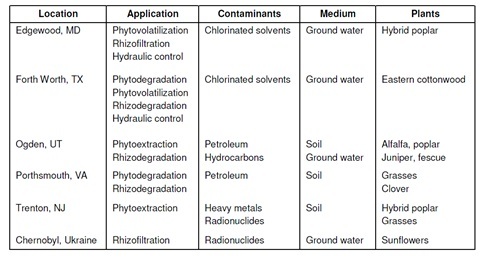

Phyto-engineering methods have been proven effective for treating soil and groundwater contamination at numerous sites throughout the world, and are accepted as a viable remediation strategy by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Environment Canada, and other regulatory agencies worldwide. Below is a table, adapted from the EPA that lists locations throughout the United States where phyto-engineering techniques have been successfully used.

However, phyto-engineering is also a preferred method for remediating contaminated sites, improving soil structure, or reducing erosion throughout the developing world. Below are a discussion of several successful pilot projects used in Zimbabwe and India.

Success of Pilot Programs[edit | edit source]

The sections below discuss previously implemented bioremediation systems in developing countries and some of the benefits and setbacks these systems encountered. By studying previous bioremediation attempts in developing countries, past successes and failures help to develop a procedure for future implementation of any new technology in similar areas.

Duckweed Ponds in Zimbabwe[edit | edit source]

Various research projects have been implemented in Zimbabwe using duckweed-based pond systems as a form of natural wastewater treatment. Several varieties of duckweed plants thrive throughout almost all of Zimbabwe making it a readily available material for use in the bioremediation system. Studies have shown the duckweed-based pond to be successful at remediating wastewater in medium to low-density residential communities. Before remediation in the lagoon, the influent quality of raw sewage in Zimbabwe requires it must be pre-treated to reduce its concentration before entering the duckweed-covered lagoon. This can easily be accomplished by including a pair of parallel anaerobic ponds as a form of pretreatment. This study[37] discovered that harvested duckweed from these systems is suitable for use as poultry feed and could potentially supply a large poultry project. This would economically benefit the community along with off-setting remediation costs.

Remediation of oil-spilled site in India[edit | edit source]

In Tamilnadu, India a bioremediation project was implemented at Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd (BHEL) in order to test the ability of applying naturally adapted microbes to on site field trials as a new approach to bioremediation. The goal of this project was to remediate this area which liberates a large volume of aqueous oil-effluent into the Uyyakondan canal, a tributary of the Cauvery River. Due to the restraints placed on specific bioremediation practices by the government in many developing countries, including India, a naturally occurring bacterium was isolated and then reintroduced into the environment to test its ability to successfully remediate oil-contaminated soil. Pseudomonas putida was successfully isolated from the oil-contaminated sites of BHEL and cultured by enrichment techniques from the effluent-polluted oil which had been contaminated over a long period of time. In order to test the viability of the microbes, as well as the overall remediating abilities they posses, replicate field plots were constructed for five treatments: control, plus oil, plus oil and fertilizer, plus oil and bacteria, and control plus oil, bacteria, and fertilizer. From these plots soil samples were collected periodically and analyzed for bacterial counts, hydrocarbons, and the physiochemical parameters of the soil. Ultimately, data that was gathered revealed that application of the fertilizer plus microbes resulted in marginally higher rate of oil substrate utilization. An increase in the microbial population’s viable cells was directly related to the rate of degradation in oil indicating a very successful rate of oil consumption (utilization of the crude oil by the microbes) in the plots that had received fertilized treatments. The overall conclusions provided by the study’s results highly supported the application of the fertilizer, urea, as resulting in not only rapid multiplication of bacteria, but also accelerating the disappearance of the hydrocarbons. While the original goal was to gauge the success of microbes by themselves, in the end it was concluded that remediation of the oil contaminated soils would not have been nearly as successful without applying the fertilizer. However, the study concluded that bioremediation by applying nutrients along with microbes well adapted to a particular environment should be considered an effective method for combating oil contaminated areas. Furthermore, urea usually has the lowest cost per pound compared to other nitrogen fertilizers. The results produced from this study bode well for the environmental concerns facing developing countries. Especially in regard to the struggles many countries face when dealing with government restrictions that force the development of new, creative bioremediation methods.[38]

Recommendation[edit | edit source]

In order to reduce the amount of deaths attributed to water contamination in developing countries, and based on my conclusions regarding phyto-engineering, I recommend:

• Develop effective means of monitoring existing phyto-engineering methods • Investigate needs of local community and develop working relationships with members • Tailor the phyto-engineering systems to meet local needs in developing countries • Continue effort to increase level of education involving proper waste disposal and personal hygiene

Before introducing phyto-engineering technologies to developing countries it is important to have a standardized, effective method to measure the pathogen level in remediated water. Developing a simple, yet reliable method that local community members can continue using after development of the phyto-engineered system to ensure the continuation of a safe drinking source for the community.

By including local community members in the initial development and design of the phyto-engineered system will ensure the adoption of a technology that local members understand and can afford to implement. This includes the ability of local community to afford the technology financially, to provide adequate amount of materials, and to grasp the process behind the technology.

Finally, without providing basic levels of education regarding personal hygiene and proper disposal of waste, the chance of even the remediated water becoming contaminated again is higher. Basic sanitation education should be included which provides instructions on proper handling of water from the remediated source up to the consumption.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lee, C.R., Price, R.A., Palazzo, A.J. & Blaylock, M. (2003). Phyto-engineering: The use of plant and biological system to accomplish engineering objectives. Poster session, Poster Board Number: 320.

- ↑ Mitsch, W.J. (1996). Ecological engineering: A new paradigm for engineers and ecologists. In: Schulze, P.C. (Ed.), Engineering Within Ecological Constraints. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp. 111-128.

- ↑ Mitsch, W. J., and S. E. Jorgensen (2003). Ecological engineering: A field whose time has come. Ecological engineering 20, 363-377.

- ↑ Mitsch, W. J., and S. E. Jorgensen (2003). Ecological engineering: A field whose time has come. Ecological engineering 20, 363-377.

- ↑ Troquet, J., & Troquet, M. (2002). Economic aspects of polluted soil bioremediation, 267.

- ↑ Ho, G. (2004). Bioremediation, phytotechnology and artificial groundwater recharge: Potential applications and technology transfer issues for developing countries. Industry and Environment, 27(1), 35.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Ho, G. (2004). Bioremediation, phytotechnology and artificial groundwater recharge: Potential applications and technology transfer issues for developing countries. Industry and Environment, 27(1), 35.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Ho, G. (2004). Bioremediation, phytotechnology and artificial groundwater recharge: Potential applications and technology transfer issues for developing countries. Industry and Environment, 27(1), 35.

- ↑ Arias, M. E. (2009). Feasibility of using constructed treatment wetlands for municipal wastewater treatment in the Bogotá savannah, Colombia. Ecological engineering, 35(7), 1070-1078.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC). 2009. Phytotechnology Technical and Regulatory Guidance and Decision Trees, Revised. Phyto-3

- ↑ Rai, P K. (2012). An eco-sustainable green approach for heavy metals management: Two case studies of developing industrial region. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 184(1), 421-448.

- ↑ Rai, P K. (2012). An eco-sustainable green approach for heavy metals management: Two case studies of developing industrial region. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 184(1), 421-448

- ↑ Qadir, M. 2002. Vegetative bioremediation of calcareous sodic soils: History, mechanisms, and evaluation. Irrigation Science 21(3): 91-101.

- ↑ Qadir, M. 2002. Vegetative bioremediation of calcareous sodic soils: History, mechanisms, and evaluation. Irrigation Science 21(3): 91-101.

- ↑ Rittmann, B. E. (1996). State-of-the-art in bioremediation methods: Promise and challenge, 429.

- ↑ Nature Wastes Nothing. (2007). Retrieved April 20, 2009, from http://www.cpreec.org/ pubbook-nature.htm

- ↑ Lewis, A. C., Baird, D. R., & Burton, S. (2004). A "poplar" solution to groundwater contamination. Radwaste magazine, 11(5), 15.

- ↑ Arias, M. E. (2009). Feasibility of using constructed treatment wetlands for municipal wastewater treatment in the Bogotá savannah, Colombia. Ecological engineering, 35(7), 1070-1078.

- ↑ Kadlec, R.H., Knight, R.L. (1996). Treatment Wetlands. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- ↑ Buscheck, T.A., et al. (1991). Infiltration of a liquid front in an unsaturated, fractured, porous-medium. Water Resources Research. Vol. 27, p. 2099.

- ↑ Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC). 2009. Phytotechnology Technical and Regulatory Guidance and Decision Trees, Revised. Phyto-3

- ↑ Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC). 2009. Phytotechnology Technical and Regulatory Guidance and Decision Trees, Revised. Phyto-3

- ↑ Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC). 2009. Phytotechnology Technical and Regulatory Guidance and Decision Trees, Revised. Phyto-3

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Robinson, B., Green, S., Mills, T., Clothier, B., van der Velde, M., Laplane, R., et al. (2003). Phytoremediation: Using plants as biopumps to improve degraded environments. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 41(3), 599.

- ↑ Lewis, A. C., Baird, D. R., & Burton, S. (2004). A "poplar" solution to groundwater contamination. Radwaste magazine, 11(5), 15.

- ↑ Rittmann, B. E. (1996). State-of-the-art in bioremediation methods: Promise and challenge, 429.

- ↑ Ho, G. (2004). Bioremediation, phytotechnology and artificial groundwater recharge: Potential applications and technology transfer issues for developing countries. Industry and Environment, 27(1), 35.

- ↑ Robinson, B., Green, S., Mills, T., Clothier, B., van der Velde, M., Laplane, R., et al. (2003). Phytoremediation: Using plants as biopumps to improve degraded environments. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 41(3), 599.

- ↑ Ho, G. (2004). Bioremediation, phytotechnology and artificial groundwater recharge: Potential applications and technology transfer issues for developing countries. Industry and Environment, 27(1), 35.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1999. Free water surface wetlands for wastewater treatment: A technology assessment. EPA 832/R-99/002. Office of Water, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Nhapi, I. (2004). Potential for the use of duckweed-based pond systems in Zimbabwe. Water S.A, 30(1), 115.

- ↑ Raghavan, P. U. M., & Vivekanandan, M. (1999). Bioremediation of oil-spilled sites through seeding of naturally adapted pseudomonas putida. International biodeterioration biodegradation, 44(1), 29.

Additional Sources[edit | edit source]

Abioye, O. P. (2011). Phytotreatment of soil contaminated with used lubricating oil using hibiscus cannabinus. Biodegradation, 1-10.

Bezama, A., Szarka, N., Navia, R., Konrad, O., & Lorber, K. E. (2007). Lessons learned for a more efficient knowledge and technology transfer to south american countries in the fields of solid waste and contaminated sites management. Waste Management Research, 25(2), 148.

Boschi-Pinto, C., Velebit, L., & Shibuya, K. (2008). Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86(9), 710-B.

Erakhrumen, A. A. (2007). Phytoremeidation: An environmentally sound technology for pollution prevention, control and remediation in developing countries. Education research and review, 2(7), 151-156.

Freshwater Availability Cubic Meters Per Person and Per Year 2007. (2007). Retrieved April 14, 2009, from http://web.archive.org/web/20090422133956/http://www.globalpolicy.org///socecon/envronmt/tables/freshwater.htm

Todd, J., Josephson, B. (1996). The design of living technologies for waste treatment. Ecological Engineering. (6), 109-136.

Kefi, M. (2011). Assessment of the effects of vegetation on soil erosion risk by water: A case of study of the batta watershed in Tunisia. Environmental earth sciences, 64(3), 707-719.

Kivaisi, A. K. (2001). The potential for constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment and reuse in developing countries: a review. Ecological engineering, 16, 545-560.

Lang, W. (1998). Farming systems as an approach to agro-ecological engineering, Ecological engineering, 11, 27-35.

Lewis, A. C., Baird, D. R., & Burton, S. (2004). A "poplar" solution to groundwater contamination. Radwaste magazine, 11(5), 15.

Liu, C. (2012). Utilize heavy metal-contaminated farmland to develop bioenergy. Advanced materials research, 414, 254-261

Luis, H., Bada, C., & Carreazo, N. Y. (2008). Improved drinking water and diarrhoeal morbidity and mortality in developing countries: A critical review. International Journal of Environment and Health, 2(1), 107.

Martin, J. F., Roy, E. D., Diemont, S. A.W., & Ferguson, B. G. (2010). Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): Ideas, inspiration, and designs for ecological engineering. Ecological engineering, 36, 839-849.

Madyiwa, S. (2003). Greenhouse studies on the phyto-extraction capacity of cynodon nlemfuensis for lead and cadmium under irrigation with treated wastewater. Physics and chemistry of the earth, 28(20), 859-867.

Nature Wastes Nothing. (2007). Retrieved April 20, 2009, from http://www.cpreec.org/ pubbook-nature.htm

Reitano, R. (2011). Water harvesting and water collection systems in Mediterranean area: the case of Malta. Procedia Engineering, 21, 81-88.

Rogers, P. (2008). Facing the freshwater crisis. Scientific American, 298(8), 28.

Singhirunnusorn, W. (2009). Appropriate wastewater treatment systems for developing countries: Criteria and indictor assessment in Thailand. Water science and technology, 59(9), 1873-1884.

Wang, W. (2010). Ecological restoration of polluted plain rivers within the Haihe river basin in china. Water, air and soil pollution, 211(1), 341-357

Wu, S. (2011). Performance of integrated household constructed wetland for domestic wastewater treatment in rural areas. Ecological engineering 37(6), 948-954.