Music is a medium through which most humans find some form of enjoyment. With advances in modern technology, it has become easy for musicians to distribute their recordings all over the world. The method by which music tracks are recorded may or may not portray the emotions and creativity of the artist who created them. Advances in materials science has allowed the design of sound isolating recording studios. These studios not only block out external noises, but they also reduce unwanted echoes/reverberations that can negatively effect the recording process. In this article, the use of polyurethane, polymeric and metallic acoustic materials for reverberation/transmission reduction will be examined.

Reducing Noise Levels and Controlling Echoes[edit | edit source]

All materials have some acoustic properties. These properties relate to the physical composition of the material. With respect to echoes and reverberation, acoustic materials for use in studios and/or noise reduction situations are designed to absorb sound energy. The sound energy that is not absorbed is ether reflected, dissipated or transmitted.[1] The sound absorbing coefficient of a material describes its sound absorbing properties. This coefficient varies from 0 to 1, with 1 representing total absorption and 0 representing total reflection. Sound absorbers tend to allow for the transmission of sound while sound reflectors do not transmit sound energy, but can cause significant echo effects.[1]

Porous Sound Absorbers

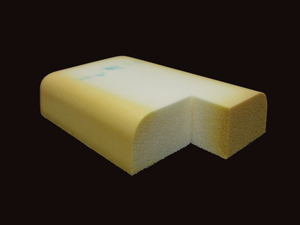

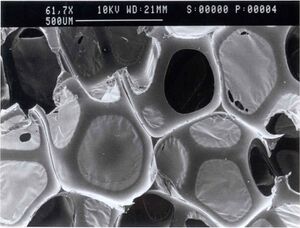

Materials with a high porosity tend to have a high sound absorption coefficient. Materials such as polyurethane foam contain a cellular structure which allows air to flow into and the absorbed sound energy is converted into heat.[1] Generally, a large material thickness is required in order to provide sufficient sound absorption, especially when used in conjunction with high density construction materials (such as concrete). This increase in thickness aids in reducing low frequency reflection. The geometry of these types of absorbers is important as it can aid in the scattering of incident waves to further absorb the sound energy.[2]

Flexural Sound Absorbers

These types of materials are generally non-porous, elastic materials which flex due to excitation from sound energy/pressure. Flexural sound absorbers are typically most effective at absorbing low frequencies, unlike porous materials.[1]

High Density Sound Attenuators

These acoustic materials can be used in conjunction with the low density porous materials to create an effective recording/listening environment. Materials with a high density generally attenuate sound energy effectively, but they cannot be in direct contact with other structural materials if total sound isolation is required.[3] The sound energy will cause these types of materials to resonate, which reduces the overall transmission of sound, but when in contact with another surface, can produce unwanted vibrations.

Attenuated Energy Formulation[edit | edit source]

Most forms of porous media exhibit some form of wave energy damping as the wave propagates through the medium. The porosity of a material can be represented by its pneumatic permeability tensor, considering the three dimensional case. However, if the material in question is assumed to be isotropic, this simplifies to just the pneumatic permeability. The other parameter that affects the material's dissipation potential is the wave velocity vector. When combining these terms, a type of pseudo dissipation potential is formed. The relationship can be described as follows:

In this equation, E is the pneumatic permeability and w is the wave velocity vector. This equation is only useful for the acoustical comparison of different materials and actual acoustical attenuation properties must be examined experimentally.

Analysis of Polyurethane Foam[edit | edit source]

Polyurethane foam is created via a basic addition polymerization reaction involving a diol or polyol, a diisocyanate, and water.[4]

A urethane polymer is created as the dissocyanate reacts with the diol or polyol. Water reacts with some of the isocyanate groups and carbon dioxide is produced. As the liquid polymerizes, expands and solidifies, some of these gas bubbles become trapped. Acoustic foams have mainly open cells due to trapped gas bubbles which pop. Air is able to pass through this type foam easily.[4]

Effects on Acoustic Properties

With respect to acoustics, there are four important material properties that effect the performance of a given material.

Elastic Properties

- The stiffness of the material is governed by its geometry, topology and microstructural interfaces.[5]

Viscoelastic Properties

- These properties describe the solid damping of the material. These are predominantly affected by the material geometry.[5]

Acoustic Properties

- The acoustic properties are governed by the fluid medium through which the sound waves propagate.[5]

Viscoacoustic Properties

- The fluid damping of the material is governed by its geometry, topology and microstructural interfaces, similar to the elastic properties.[5]

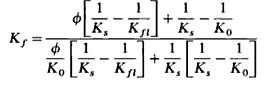

By varying material properties, such as density, the elastic and viscoelastic components of sound energy attenuation can be modified. The acoustic and viscoacoustic properties are reliant on the viscous drag constant and the pore fluid bulk modulus.[5] Using Biot's Theory and Gassmann's Formulation, the saturated bulk modulus may be calculated using Eq.1 shown in Fig. 4.

Kf represents the bulk modulus of saturated polyurethane, Ks represents the bulk modulus of the foam structure surrounding the pores, Kfl represents the bulk modulus of the fluid within the foam (in this case, air) and K0 represents the dry bulk modulus of the polyurethane.

Polyurethane is modeled as a flexible, open-cell, porous solid. Sound energy is transmitted through the material by two main methods:[6]

- Sound pressure waves propagate through the fluid in the pores of the polyurethane

- Elastic stress waves are induced due to the pressure waves, which are carried through the frame of the polyurethane

Acoustic Properties of Polymers

As discussed, polyurethane is quite effective at attenuating high frequency sound waves, but it fails to provide low frequency isolation unless an adequate thickness is used. The porous nature of polyurethane greatly reduces acoustic reflection, but this low density also allows for the transmission of sound energy. Polymers may also be used as acoustic dampers. With respect to polymers, there are two main modes of acoustical propagation: Longitudinal and Shear.[7] Longitudinal waves may also be referred to as compression, or dilatation waves. These waves involve local compressions and expansions within the material. The individual particles of the material vibrate normal to the direction of the excitation propagation. In shear waves, or transverse waves, an oscillating shear wave is created by the local shear forces induced within the material due to the sound wave. Movement of individual particles within the material due to these waves occurs in a direction parallel to the wavefront. From these longitudinal and shear waves, it can be shown that to describe the acoustic properties of a polymer, four parameters must be examined.[7]

- Longitudinal speed, uL

- Shear speed, uSh

- Longitudinal absorption, αLt

- Shear absorption, αSh

Sound absorption within a polymeric structure is related to a number of molecular mechanisms such as the glass transition, curing, annealing etc.[7] The total attenuation (energy loss) is the sum of all the scattering, reflecting and absorbing energy totals for a given material.

Density and Crystallinity Effect on Sound Speed

The degree of crystallinity of a polymer effects its density and moduli.[7] The speed of sound is also dependent on these parameters and will thus be affected by them. At the present time, more research is needed into this area as often experimental results don't agree with theoretical models.[7] It has been shown that the speed of a longitudinal wave uLin a material is proportional to , where E is the Young's Modulus and p is the material density. However, experimental results suggest that the speed of sound varies linearly with these properties.[7]

Porosity in Polymers[edit | edit source]

Usually porous polymers are prepared by co-polymerizing styrene and divinylbenzene. The result is a polymer containing micro-scaled pores that is generally weak due to the lack of cross-linking between monomer chains. These types of porous polymers are usually referred to as gels due to the low amount of cross-linking.[8] In order to retain the desired mechanical properties of the polymer, another porous version was created by scientists know as macro-porous polymers. In these polymers, pores are formed independently of cross-linking. Porogens are used during polymerization as they are soluble in monomers, but insoluble in formed polymers. This causes the creation of pores, as the polymer cannot form in any region where a porogen is located. This creates a polymer structure with a maximum porosity of 50% while maintaining mechanical properties.[8]

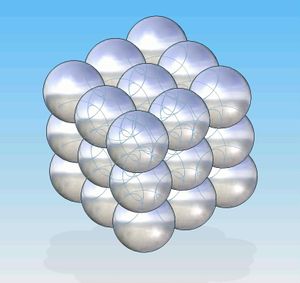

Porosity in Metals[edit | edit source]

The desirable characteristics of acoustic damping materials may be further improved through the use of porous metals. Similar to porous polymers, metals may be created (even on the macro scale) which have a completely interconnected porous structure..[9] This interconnected porosity is critical in the acoustic performance of a material due to the fluid medium that is required for sound waves to propagate. A porous metal sample provides similar damping characteristics as a polyurethane foam sample, while retaining a high elastic modulus. The formation of these metals is relatively easy also, and involves a process called sintering.

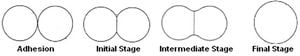

- Formation of Porous Metals

As mentioned, most porous metals are formed via sintering. Sintering involves the use of small particles which are "sintered" together using a furnace at high temperature. These particles are not necessarily spherical, however for modeling purposes, the spherical case will be examined here. The process has four stages, shown in Figure 6. For acoustical applications, the solid-state sintering technique of Gravity Sintering is useful. It should also be noted that the method of Axial Compaction sintering (this is similar to gravity sintering with an added processing step involving the compaction of metallic particles under high force) could be employed, however gravity sintering usually provides a greater interconnected porosity due to the lack of particle compaction.[9] In gravity sintering, the creation of a porous structure is dependent on the diffusion bonding of adjacent particles. Generally, finer material powders can be sintered at lower temperatures due to the increased driving force from the surface energy of the smaller particles. At higher sintering temperatures, the necking stage occurs more rapidly and larger pores are created.[9] This usually results in a non-uniform porosity. Therefore, for acoustic damping, it is desirable to expose the metal particles to the required sintering temperature for a minimal time period. The diffusion flux for surface diffusion can be seen in the following equation:

- Js=[(-δs Ds Ωγs)/kT] dK/ds

In this equation, the -δs term represents the thickness of the surface layer, Ds represents the surface diffusivity, Ω represents the atomic volume, γs is the surface energy, k is Boltzmann's constant, T is the sintering temperature and the dK/ds term relates to the neck curvature. The equation for the diffusion flux along grain boundaries is very similar to this equation, with the neck curvature term replaced by a volume density of chemical potential term. It may also be noted that the neck diameter between adjacent particles grows proportional to the square root of the sintering time.[9]

Applications of Acoustic Damping Materials[edit | edit source]

Most applications of acoustic damping involve some form of sound engineering/recording. In recording studios, ambient noise is unwanted and must be kept to a minimum. At the same time, reverberation must be controlled in order to record tracks properly. However, there are other applications of acoustic damping materials. These types of materials could be used to reduce cabin noise on commercial airliners. Furthermore, in manufacturing plants where noise pollution is a problem, acoustic damping materials may be used to lessen the strain on worker's ears and prevent hearing loss due to loud machinery.

Economics[edit | edit source]

As discussed, ususally large thickness of polyurethane foam are required for significant damping of a wide frequency spectrum. By using a porous metal, the amount of material could be reduced, correlating to a direct cost savings. The following table shows a sample calculation which compares the cost of a acoustic polyurethane to a porous metal. The comparison was made for a damping area of 2.50 m2.

| Porous Aluminum Analysis | Polyurethane Foam Cost Analysis |

|---|---|

| Density = 2.70 g/cm3 | Average Sheet Volume = 5.08 x 137.16 x 182.88 cm |

| Cost per unit mass = $1.00/lb | Cost for the average sheet volume = $133.65 |

| Volumetric Cost = $5.967 x 10-3/cm3 | Volumetric Cost = $1.05 x 10-3/cm3 |

Using the table values, an aluminum volumetric porosity of 70% and a thickness ratio of 0.25:1 (Aluminum to Polyurethane Foam), the cost of each material was calculated. The results are shown in the table below.

| Final Cost |

|---|

| Porous Aluminum = $112.07 |

| Polyurethane Foam = $133.79 |

This estimate illustrates how the reduced volume of the porous aluminum impacts the material cost. Standard cost values for aluminum and polyurethane were determined through research.[10]

Reducing the Volume of Acoustic Damping Materials[edit | edit source]

As discussed earlier, acoustic foam (polyurethane) requires a relatively large thickness in order to provide sufficient damping of low frequency sound vibrations. However, polyurethane is well suited to the reduction of higher frequencies, so a good balance between porous sound absorbing properties and flexural absorbing properties could theoretically provide a wide spectrum of frequency damping while minimizing material requirements.

- Macro-Porous Polymers

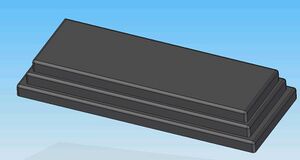

Macro-Porous polymers can provide a high level of porosity in a more dense medium when compared to polyurethane.[8] As mentioned earlier, attenuation in polyurethane is highly dependent on the thickness of the material. A macro-porous polymer acoustic damping system could provide the same damping effects as the polyurethane, while minimizing vibration transmission due to its higher density. This would reduce the amount of material needed for sound isolation. Furthermore, this technology could be used in conjunction with polyurethane to create a damping sample with variable density. Figure 6 displays a proposed acoustic damper consisting of two thin layers of varying density polyurethane foam and a single layer of macro-porous polymer. This combination could have an overall thickness that is smaller than that of a single density, polyurethane foam.

- Porous Metals

Due to the porous structure and increased elastic modulus of porous metals when compared to porous polymers,[11] these materials would be more efficient at damping out a wide range of sound frequencies. This is in part due to the increased rigidity of the metal and its ability to damp out lower frequencies of sound. A porous metal damping system would require even less material than a macro-porous polymer system, further increasing the materials savings.

Thickness Savings Calculation

The following calculation displays the reduced thickness required for equal damping potential between a polyurethane foam and a porous metal. Assuming laminar flow, the permeability of each material can be modeled using the following equation: [12]

The comparison of the two materials is shown in the table below. It is important to note that the following assumptions were made:

- A linear relationship between elastic modulus and dissipation potential[7] ()

- A constant sound wave velocity for both materials (constant omega)

- The volumetric flow across each cross section of material is constant

- The pressure drop across each cross section of material is constant

- The average elastic modulus for porous metal is approximately 0.35 GPa[13]

- The average elastic modulus for polyurethane is approximately 0.05 GPa<ref name="M">M. Fogiel, "Material Properties," in Handbook of Mathematical, Scientific, and Engineering Formulas, Tables, Functions, Graphs, Transforms,2nd ed.Staff of Research and Education Association, Ed. Piscataway, NJ: Research and Education Association, 1988, pp. 880-885.<ref>From these assumptions, it can be seen that the only variable which affects the attenuated energy is the material thickness.

| Porous Metal | Polyurethane Foam |

|---|---|

Assuming that each material provides an equal attenuation potential and using the stated parameter assumptions, by relating the equations using ratios, it can be seen that the thickness are related in the following manner:

Therefore, using a porous metal results in an 85% thickness reduction.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Porous metals have proven to be very promising for acoustic damping situations. They are easy to manufacture and provide significant gains in sound energy damping when compared to polyurethane foams. As the technology progresses, these types of materials will become more commonplace in standard engineering situations.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 David R. Schwind. (1997, Room acoustics: Basic principles of reflection, diffusion and absorption. 2009(11/12), pp. 1. Available: http://web.archive.org/web/20141012203448/http://www.mixonline.com:80/online_extras/sound_absorbing_materials/

- ↑ Silex, "Sound Attenuation," vol. 2009, pp. 16, 4/5/2002. 2002.

- ↑ D. Takahashi and M. Tanaka. (2002, February 27, 2009). Flexural vibration of perforated plates and porous elastic materials under acoustic loading. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 112(4), pp. 11/10. Available: http://scitation.aip.org.proxy.queensu.ca/getabs/servlet/GetabsServlet?prog=normal&id=JASMAN000112000004001456000001&idtype=cvips&gifs=yes

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Linda Wang. (2006, January, 2006). Polyurethane foam. 2009(11/10), pp. 1. Available: http://pubs.acs.org.proxy.queensu.ca/cen/whatstuff/84/8402foam.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 T. Bourbie, O. Coussy and B. Zinszner. (1987, "Wave propagation in saturated porous media," in Acoustics of Porous Media (1st ed.) Anonymous Available: http://books.google.ca.proxy.queensu.ca/books?id=2ozNKWDUXU4C&pg=PA63&lpg=PA63&dq=biot's+theory&source=bl&ots=Epqbc7fzPm&sig=UhKV4iKWE9RAQ4fV_oP9XWEOfFY&hl=en&ei=JDr8SpGpIcP-nQeN3MGYBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CDAQ6AEwBzgK#v=onepage&q=biot's%20theory&f=false

- ↑ Peter Goransson. (2006, January, 2006). Acoustic and vibrational damping in porous solids. 364(1838), pp. 11/11/2009. Available: http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org.proxy.queensu.ca/content/364/1838/89.full#sec-6

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 D.W. van Krevelen and Klaas te Nijenhuis, "Acoustic properties of polymers," in Properties of Polymers,4th ed.Anonymous Netherlands: Elsevier, 2009, pp. 50-50-110.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 P. James R. Benson. (2003, April, 2003). Highly porous polymers. 2009(11/11), pp. 14. Available: http://web.archive.org/web/20111215133033/http://www.polygenetics.com:80/PDF%20Files/Porous%20Polymers%202003.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 H.E. Exner and E. Artz, "Solid-state sintering," in,4th ed.Robert W. Cahn and Peter Haasen, Eds. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science, 1996, pp. 2628-2637

- ↑ S. Kalpakjian and S. Schmid, "Metal casting: Design, materials, and economics," in Manufacturing Engineering and Technology,5th ed.E. Svendsen, Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2006, pp. 323-357.

- ↑ C. Zang, H. Tang and J. Wang, "Research progress on mechanical properties of sintered metallic porous materials," Xiyou Jinshu Cailiao Yu Gongcheng (Rare Metal Materials and Engineering).Vol.38, vol. 38, pp. 437-442, pp. 437-442. Apr. 2009.

- ↑ M. W. Quintero, J. A. Escobar, A. Rey, A. Sarmiento, C. R. Rambo, A. P. N. De Oliveira and D. Hotza, "Flexible polyurethane foams as templates for cellular glass-ceramics," Journal of Materials Processing Technology.Vol.209, vol. 209, pp. 5313-5318, pp. 5313-5318. July. 2009.

- ↑ P. Nieuwkoop, "Aluminum foam: production, properties, and processing," Constructeur.Vol.44, vol. 44, pp. 26-30, pp. 26-30. Jan.-Feb. 2005.