Need

The conversation surrounding energy consumption in the United States often hones in on dependency on foreign oil, the extent to which fossil fuel consumption contributes to global climate change, etc. Certainly, these are very pressing problems that will need to be addressed soon, but there is a second energy crisis that often is overlooked. While developed nations consume fossil fuels at an alarming rate, nearly 2 billion of the world's population is without electricity and is still heavily reliant on traditional fuels such as dung, wood, and other forms of biomass. [1] Thus far, efforts to reverse this trend have focused on a two-pronged approach: one, increase access to "modern" form of energy in an inexpensive, responsible way; and second, to make the current use of biofuels safer and more sustainable. While this is a worthwhile approach, it is not comprehensive.

For centuries, human and animal power have been utilized, and their importance in the portfolio of a comprehensive strategy for addressing the energy crisis in developing countries should not be ignored. An estimated 1200 petajoules were produced by humans without electricity for the purpose of work in the year 2008. This is over 1.5 times that of wind energy produced in the same year![2] Much of this effort was expended in menial, repetitive tasks that can be made more efficient with human powered machines.

History

The use of tools as an extension of human power is much older than recorded history. The earliest known encyclopedia of games in Europe, Libro de Juegos (Book of Games), commissioned by King Alfonso X of Castille in 1283, depicts a bow lathe being used to turn backgammon pieces. This type of device is still in use today by artisans in Morocco.

From the Middle Ages and onward, labor-saving devices were improved upon for use in the home and on an industrial scale. Perhaps the most important of such machines was the cotton gin. Eli Whitney's simple mechanical solution to the painstaking chore of processing cotton increased productivity by fifty times.[4] Rather than decrease the need for slave labor in the American South, the cotton gin reaffirmed the demand for slaves. Thus, the human-powered cotton gin inadvertently changed the course of the history.

The late 19th century saw the development of the bicycle. Over the following decades, it would evolve from little more than a plank with two wheels to the familiar diamond frame we see today. Countless improvements, including multiple speeds, have made the bicycle the most efficient means of human-powered transportation. Because of its prominence in the history of human power, bicycle technology has been launching point for many endeavors to capitalize on excess human energy. In the developed world, gyms are beginning to harness the power expended on stationary bikes for their electrical needs.[5]

In last twenty years, attention has been increasingly paid to harvesting human energy in more unconventional ways. For instance, piezoelectric crystals, which produce electricity under tension or compression, are becoming cheaper and less fragile. Although their electrical production is very small, it is hoped that an array of such devices could be integrated into clothing to obtain the vibrational energy of a person, for the purpose of powering mobile electronics. [6][7] Another application of such technologies would be the integration of miniature generators located at the joints of the knees, for harvesting excess energy [8] While such innovations are certainly promising, they are prohibitively expensive for even the developed world at this point.

Design Considerations

Culture

The cartoon to the right appeared in 1895 periodical called Punch. At this time in European and U.S. history, the emerging culture of cycling brought with it cultural changes, such as the gradual acceptance of women wearing pants. In the cartoon, parallels are drawn between the domestic use of treadle sewing machines and bicycles, to illustrate the sense of empowerment that cycling culture gave women in turn of the century Great Britain.

In the modern era, there may be similar cultural obstacles to the social acceptability of a pedal-powered machine. For instance, women may discouraged from straddling the seat of a bicycle. In such cases, it would be necessary to redesign the machine for a recumbent or reclined orientation. If the labor requirement of the job is not too much, a hand crank may be substituted for pedal power, like that of a pull-start motor. [10]

As a case of unanticipated cultural issues with a technology, the Universal Nut Sheller found great success in Malian communities for peanut shelling. This success was not duplicated in Ghanaian communities, however, who shell shea nuts as a community activity.[11]

Logistics

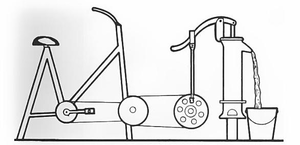

Another consideration before the implementation of a human-powered machine is ability of the community to secure the parts and technical expertise to both construct the machine and keep it in operation. One general guideline for the potential for human-powered machinery is the use of bicycles. If these are in wide use, if parts are reasonably easy to obtain, and if repair of bicycles occurs locally, then other applications of pedal power may be feasible.

In addition to local support of bicycle infrastructure, it would be beneficial to have local access to either carpentry or metalworking skills, for the construction of the frame of the machine.

Application

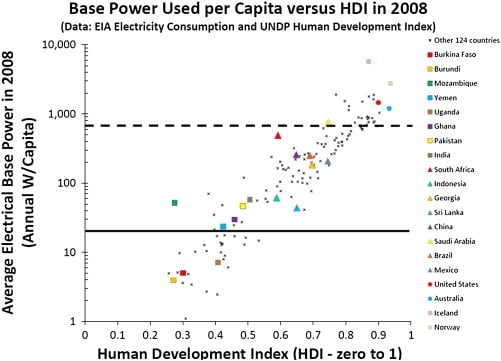

The figure below shows the relationship between the Human Development Index and Base Power Consumption. The solid black line designates those countries which will benefit from electrical power generation using a human-powered device. The countries between the dotted and solid lines have an unreliable electrical grid or limited electrical access, but may also receive a benefit from human-powered electricity. This principle may be broadened to include other modes of utilizing human power.[12]

Candidates for human power [13]

Power generation for lights

Fuel based replacer [15]

high capacity vehicle [16]

Washing Machine [17]

Human physiology [18]

Theory

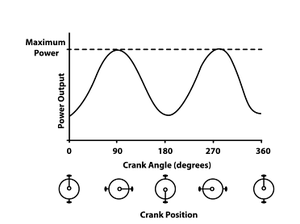

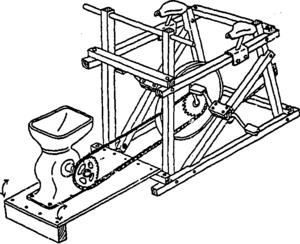

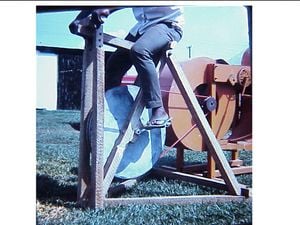

The natural action of pedaling a bicycle, essentially transforming linear motion into circular motion, creates an oscillatory power function as seen in Figure 2.

In the case of a mobile bicycle, this effect is masked by three factors: inertia provided by the weight of the rider; frictional losses from equipment; and drag forces from the air. For stationary riders (people operating human-powered machines), however, this phenomenon comes becomes an important consideration in power delivery. For instance, for the milling of grains, it would be favorable to provide a more or less constant power to mill, to facilitate a consistent feed rate through the machine. For this reason, it is often prudent to introduce a means of “smoothing” the power output from the driven gear. The most common way of this is through a flywheel. A flywheel is a rotating mass used in mechanical systems for energy storage. It will substitute for the inertial mass that the rider's weight provides in the mobile example.

For a circular hoop (imagine a bicycle wheel) of radius 'r' and mass 'm', moment of inertia I, is defined by

For a solid disk or cylinder of radius 'r' and mass 'm', the moment of inertia I is given by

Additionally, the kinetic energy of a flywheel is given by where is the angular velocity of the flywheel.

From initial inspection, we can see that for the same mass, the hoop has a higher moment of inertia, by a factor of 2. From an energy perspective, as compared to a solid cylinder, the hoop takes twice as long to reach a steady speed, but takes twice as long to slow down, all things held equal. The primary advantage of a solid-disk flywheel, however, is ease of manufacture.

There have been several proposed designs for a method of power smoothing that does not require a spinning mass. In particular, a reciprocating spring system and an electrical circuit employing a large capacitor have been suggested. [20] Such systems seek to the portability of human-powered machines. While the massless mechanical system has not seen wide distribution, the later has found use in electrical power generation, in applications that require steady voltage input.[21] [22]

Construction

Construction of a human-powered machine can be

drawbacks of bike-based generators [25]

Evaluation

In the realm of electrical power generation, a notable participant in harnessing human energy is NURU Energy.[26]

Impact

Dissemination

While the overall climate for human-powered machinery seems to revolve around bringing power to the developed world, there is domestic interest to resurrect some of this "antiquated" technologies for domestic use. For example, Fender Blender offers a pedal-powered base, inspired by cruiser bicycle aesthetics, for use with a standard blender. Additionally, all of the plastic parts of the machine are made from recycled plastics. [27]

One success story of the implementation of human power, outside of the realm of pedal power is the treadle pump. [28]

Education for Sustain [29]

See also

- Animal-powered devices

- Washing and drying clothes

- Bicycle sharing station providing power back to the mains electricity grid[30]

External links

- Pedal Power at CCAT

- Human Powered Appliances discussion at bikeforums.net

- Green MicroGym: contains Human Dynamo, and SportsArt EcoPowr treadmills

- MNM Power, another company making peda power products

- Lucien Gambarota's MotorGym Co Ltd's devices, used by the California Fitness company in Hongkong

- Woodway EcoMill

- Pedal-A-Watt, device for use on bikes

References

- ↑ Barnes, D.F. and W.M. Floor, RURAL ENERGY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: A Challenge for Economic Development1. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 1996. 21(1): p. 497-530.

- ↑ Fuller, R.J. and L. Aye, Human and animal power – The forgotten renewables. Renewable Energy, 2012. 48(0): p. 326-332.

- ↑ http://thomasguild.blogspot.com/2012/06/woodworking-tools-in-libro-de-los.html

- ↑ Woods, Robert. “A Turn of the Crank Started the Civil War." Mechanical Engineering.

- ↑ Benkatraman, V. An electric workout through pedal power. The Christian Science Monitor, 2008.

- ↑ Starner, T. and J.A. Paradiso, Human Generated Power for Mobile Electronics. Low Power Electronics Design, 2004.

- ↑ Gonzalez, J.L., A. Rubio, and F. Moll, Human Powered Piezoelectric Batteries to Supply Power to Wearable Electronic Devices. International Journal of the Society of Materials Engineering for Resources, 2002. 10(1).

- ↑ Donelan, J.M., et al., Biomechanical Energy Harvesting: Generating Electricity During Walking with Minimal User Effort. Science, 2008. 319(5864): p. 807-810.

- ↑ Punch1895: London, United Kingdom.

- ↑ Chandler, L., Redesign of a Human Powered Battery Charger for Use in Mali, in Department of Mechanical Engineering2005, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA. p. 29.

- ↑ http://www.thefullbellyproject.org/Products/UniversalNutSheller.aspx

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mechtenberg, A.R., et al., Human power (HP) as a viable electricity portfolio option below 20 W/Capita. Energy for Sustainable Development, 2012. 16(2): p. 125-145.

- ↑ Modak, J.P., Human-Powered Flywheel Motor Concept, Design, Dynamics and Applications, 2007.

- ↑ Pedal Power, in Supplement to Energy for Rural Development1981, National Academy Press: Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Bhusal, P., A. Zahnd, and M. Eloholma, Replacing Fuel Based Lighting with Light Emitting Diodes in Developing Countries: Energy and Lighting in Rural Nepali Homes. Leukos, 2007. 3(4): p. 277-291.

- ↑ Cyders, T.J., Design of a Human-Powered Utility Vehicle for Developing Communities, in Department of Mechanical Engineering2008, Ohio University: Athens, OH.

- ↑ Raduta, R. and J. Vechakul, Bicilavadora, 2005, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA.

- ↑ Tiwari, P.S., et al., Pedal power for occupational activities: Effect of power output and pedalling rate on physiological responses. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 2011. 41(3): p. 261-267.

- ↑ Dean, T., The Human-Powered Home2008, Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers.

- ↑ Allen, J.S., In search of the massless flywheel. Human Power, 1991. 9(3).

- ↑ Butcher, D. Pedal Power Generator - Electricity from Exercise. 2012 12/16/2012 12/17/2012]; Available from: http://www.los-gatos.ca.us/davidbu/pedgen.html.

- ↑ Czap, N., Stationary bike designed to create electricity, in San Francisco Gate2008: San Francisco, CA.

- ↑ Weir, A., The Dynapod: A Pedal Power Unit, 1980, Volunteers in Technical Assistance: Mt. Rainier.

- ↑ One man dynapod, Uganda 1972, 1972, Alex Weir.

- ↑ Decker, K.D. Bike powered generators are not sustainable. Low-tech Magazine, 2011.

- ↑ NURU: Energy to Empower. POWERCycle 2012 [cited 2012 11/26/12]; Available from: http://nuruenergy.com/nuru-africa/the-solution/powercycle/.

- ↑ Fender Blender. [cited 2012 12/12/12]; Available from: http://www.rockthebike.com/fender-blender-pro/.

- ↑ The Treadle Pump, 1991, Development Technology Unit, University of Warwick, Department of Engineering: Conventry, UK.

- ↑ Clarke, P., Education for Sustainability: Becoming Naturally Smart2012, New York, NY: Routledge. 140.

- ↑ Chiyu Chen's Hybrid2 concept