HEAT PUMP TECHNOLOGY[edit | edit source]

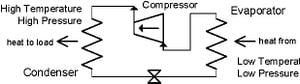

A heat pump is essentially a device that moves energy from a heat source to a heat sink using some form of work. Almost all modern heat pumps use a vapour-compression cycle as shown in Figure 1. A compressor is used to pump a refrigerant between two heat exchanger coils – a condenser and evaporator. The fluid enters the evaporator at a low pressure and absorbs heat from its surroundings. A heat pump is considered to be “direct” when the evaporator is located at the heat source. In an “indirect” configuration, a separate heat transfer loop is used to between the evaporator and the source. After passing through the evaporator, the fluid is compressed and delivered to the condenser at a high pressure. As the fluid passes through the condenser, it releases heat to the surroundings.

There are different types of heat pumps, according to the specific loops of pipes that are used to extract the heat from groundwater. For example, closed-loop systems gather energy directly from the earth. Moreover, heat is produced in a renewable way, yet the system requires little maintenance. Several configurations of closed-loop systems exist, such as horizontal or vertical heat exchangers. They can take up a radial or directional drilling direction, and they can be installed either around a pond or a lake. On the other hand, open-loop systems require more sophisticated resources to exploit - such as aquifers - since groundwater has to be used to gather heat through a heat pump.[1]

The performance of heat pumps is usually described by a coefficient of performance (COP). In heating mode, this is the ratio of the amount of heat energy delivered from the system divided by the net work input (e.g., electrical energy) to the machine. In cooling mode, the COP is given by the ratio of thermal cooling provided, divided by the work input to the machine. The COP of a heat pump is highly dependent on the temperature of the heat source. To ensure that the required loads are met and to reduce strain on the heat pump in extreme conditions, a heat pump system is typically coupled with an auxiliary heating system, such as resistance heating or a natural gas or oil furnace.

The air-to-air heat pump is the most common type of heat pump and is used widely in commercial and residential applications. In these units, the evaporator coil is run outdoors to pick up heat from the ambient air. The condenser coil is runs indoors and used in conjunction with a fan to release the heat. The term heat pump is usually referred to machines that are utilized to provide heat to a load as described above. Most heat pumps however, are reversible and can be used in a cooling or heating mode depending on the requirement.

Heat pumps can also be configured to use water or the ground as a heat source (or sink). Ground-source heat pumps typically demonstrate higher efficiencies than air-source heat pumps because the average ground temperatures are lower than air temperatures in the summer, when cooling is required; and similarly higher than average air temperatures in the winter, when heating is required. These units are typically more expensive to install as they require the use of a buried ground loop.

The use the ground as a source for heat pump systems was first suggested in 1912 in Switzerland. At the time however, fossil fuel based systems were popular as energy prices were relatively low. By the 1940’s interest in this area was revived with research conducted in both the US and UK. In 1946, the Commonwealth Building in Portland, Oregon was the first large commercial building in the United States to use heat pumps for heating and cooling (Bloomquist, 1999). Two years later in the UK, Sumner installed 12 prototype ground-source heat pump systems. Each unit has a 9 kW output and operated at an average COP of 3 (Sumner, 1976). The success of these systems unfortunately is unclear and they lack documentation. The use of the ground as a heat source/sink did not become commercially available until after the oil shock in 1973. In 2001, Lund and Freeston published the results of a survey carried out to determine the global utilization of geothermal energy. They reported an estimated 5275 MW of installed thermal capacity by means of geothermal heat pumps. This is a significant increase in installed capacity from 1995 which stood at 1854 MW.

Heat at different earth layers[edit | edit source]

Depending on the depth where you place your heat exchanger of your ground-source heat pump system, the available heat will fluctuate greatly during different times of the year, and may also be lower/higher.

- At 1m depth: available heat varies between 4°C and 17°C, depending of the season

- At 5m to 7m depth: available heat varies between 10°C and 12°C, depending of the season

- At 25m to 200m depth: available heat varies between 12°C and 15°C, depending of the season[2]

References[edit | edit source]

See also[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

- http://www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?c=geo_heat.pr_crit_geo_heat_pumps U.S. Energy Star program information on geothermal heat pumps

- http://www.google.com/search?client=googlet&q=dx%20heat%20exchanger Google search for DX (direct expansion) heat exchanger.

- http://www.ecrtech.com/go.asp?goto=flwctrl ECR owns patents on necessary refrigerant flow control devices. The diagram on this page is illuminating.