Although SODIS have been well tested - this pre-filter has only been bench tested.

To address the widespread need for safe water for drinking and sanitation purposes, a low-cost household water treatment system has been developed. The presented treatment unit serves as a means to reduce turbidity in water to be subsequently treated with solar water disinfection (SODIS) technology. The unit is comprised of a well-graded sand filter through which turbid water flows and subsequently settles. Bench scale laboratory tests were conducted on three different filter media in columns (10 cm diameter, 25 cm tall): well-graded sand (particle diameter from 0.07mm to 2mm), poorly graded Ottawa sand (particle diameter 0.6mm) and poorly graded silica sand (particle size 0.2mm). Combined filtering and settling resulted in a most effective reduction in turbidity of 99.4% in the source water, observed with the well-graded sand filter media. Settling time to achieve a clear supernatant was found to be approximately 1 day, though sufficient settling may have been achieved sooner. Based on the bench scale results, a physical model was developed and tested using a 2-L plastic beverage bottle and the well-graded sand as the filter media. The unit functioned as expected and produced turbid effluent that sufficiently settled in about 18 hours. These results suggest that similar models produced at the household level should produce acceptable results and effectively reduce turbidity, thereby optimizing the SODIS treatment method. Appropriate methods to increase the settling rate of solids in the effluent should be explored to improve this design, as the settling time may not be practical for many end users.

See Also: Decreasing turbidity to optimize solar water disinfection

Theory[edit | edit source]

The design presented below is based largely on the following background information regarding the need for water purification around the world and conventional treatment technologies.

The need for clean water[edit | edit source]

Over 1.1 billion people around the world do not have access to clean water and over 2.4 billion people do not have access to adequate sanitation.[1] This limitation puts these people - the world's poorest - at risk for contact with waterborne diseases such as cholera, dyssentry, and typhoid fever. Many waterborne infections induce diarrhea, which causes 4% of the world's deaths and is the leading cause of death among children under the age of five[2]. Other waterborne diseases, such as trachoma - the leading cause of blindness in developing countries - are rampant as a result of inadequate sanitation.

All of this calls for access to clean water for drinking and sanitation purposes. The World Health Organization, the United Nations, and Red Cross all advocate for the implementation of low-cost treatment at the household level as a means of providing water that is free of the microbiological organisms associated with waterborne diseases. The challenge rests in providing sustainable treatment methods that can be implemented in a wide range of locations and that are accepted by the end users.

Conventional physical and chemical treatment methods[edit | edit source]

The effectiveness of several different means to improve the microbial quality of household water and reduce waterborne disease has been documented around the world. Common physical treatment methods include boiling, heating (both fuel and solar sources), settling, filtering, UV disinfection from sunlight, and UV disinfection with lamps. Chemical treatment methods include coagulation-flocculation and precipitation, adsorption, ion exchange and chemical disinfection with germicidal agents such as chlorine.[1]Unfortunately, some of these methods rely on the use of chemicals and other materials that cannot be obtained locally at a feasible cost, and/or require complex systems that are not suitable for the average household user. These limitations make many of the above treatment methods inaccessible to users in certain regions of the world. It is therefore important to implement systems that are simple, low-cost, and accepted by the end user.

Solar water disinfection (SODIS)[edit | edit source]

One of the most promising methods of removing microbiological organisms associated with waterborne diseases is solar water disinfection, more commonly known as SODIS.[1] This particular application of solar UV radiation and solar heat has been developed by the Swiss Federal Agency for Environmental Science and Technology (EAWAG).

Function[edit | edit source]

The premise of the SODIS system is simple: it functions by inactivating waterborne microbes as a result of exposure to UV-A radiation and heat (pasteurization).[3] Water of low turbidity (<30 NTU) is placed in clear PET plastic or glass bottles (clear plastic bags may also be used). The water is then aerated by vigorous shaking in contact with air, as the deactivation of bacteria has shown to be more effective in oxygenated water than in anaerobic conditions.[4] This water is then exposed to direct sunlight for several hours (the official SODIS website recommends 6 hours) so that it becomes sufficiently heated and exposed to UV radiation, both of which inactivate microbes in the water[5]. If there is extensive cloud coverage, as many as 2 days will be needed for sufficient exposure to UV radiation. The system is suitable for treating small volumes of water (<10L), and water that is relatively clear (corresponding to a turbidity of <30 NTU).[1]

Advantages[edit | edit source]

Through the combined effects of UV-A radiation and heating (pasteurizing), various bacteria (fecal coliforms, E. coli, enterococci, etc.), and viruses (coliphage f2, rotavirus, encephalomyocarditis virus, etc.), can be reduced by several orders of magnitude. If temperatures of 50-60 degrees Celcius are achieved, extensive inactivation of many enteric viruses, bacteria and parasites (99.9%) can be achieved in as little as 1 hour to several hours of exposure.[1]

The SODIS method of water treatment is simple, easy to use, and very effective at deactivating waterborne microorganisms. Particularly with supporting education and motivational support, this method shows promise for widespread implementation in developing countries.

Limitations[edit | edit source]

Volume of water

The SODIS method only functions for treating relatively small volumes of water (<10 L). Furthermore, the time it takes to treat the water may not be considered practical by many end users.

Material use for UV-A radiation

The material of the container used for SODIS treatment must be clear. In batch tests conducted by the Swiss Federal Agency for Environmental Science and Technology (EAWAG) UV-A transmission losses were found to be at least six times higher in coloured bags than in transparent bags.[6]

The average UV-A transmission losses of the used transparent container material were found to be: ~30% for plastic PET bottles, ~25% for glass bottles and ~10% for plastic bags.[6]

Turbidity requirements

One of the greatest concerns with the SODIS method is the requirement of the water to be of low turbidity (<30 NTU),[1] as UV-A intensity has been shown to decrease rapidly with increasing water depth and turbidity.[6] Incidentally, source water for many households is turbid as a result of being sourced from areas subject to overland flow, flooding, or from water that has collected in shallow pools. There is therefore a need for simple, effective means of reducing turbidity to an acceptable level prior to SODIS treatment.

The World Health Organization lists the following methods for the removal of suspended matter (turbidity) from water as being potentially suitable for pre-SODIS treatment:[1]

- Settling or plain sedimentation

- Fiber, cloth or membrane filters

- Granular media filters and

- Slow sand filter

There is huge potential to optimize the functionality of the SODIS method by ensuring that the water to be treated is as clear as possible. Care must be taken to ensure that this employs simple, practical mechanisms that will be easily employed by the end user.

Design of a low-cost water treatment system to reduce turbidity[edit | edit source]

The following design functions as a pre-treatment to solar disinfection and is based on filtering and settling mechanisms to reduce turbidity. If used correctly, it will markedly reduce the turbidity of water to be treated with solar disinfection, thereby optimizing its effectiveness.

The design is based on the results of bench-scale experiments discussed in the 'Supporting Experimentation and Results' section below. The accompanying report can be found here:

Bench test results showed that this system has the potential to significantly reduce turbidity: reductions of up to 99.4% (as low as <5 NTU) were observed. It should be noted that turbidity readings could not be taken for the physical test that was modeled after the bench tests but similar qualitative results were observed.

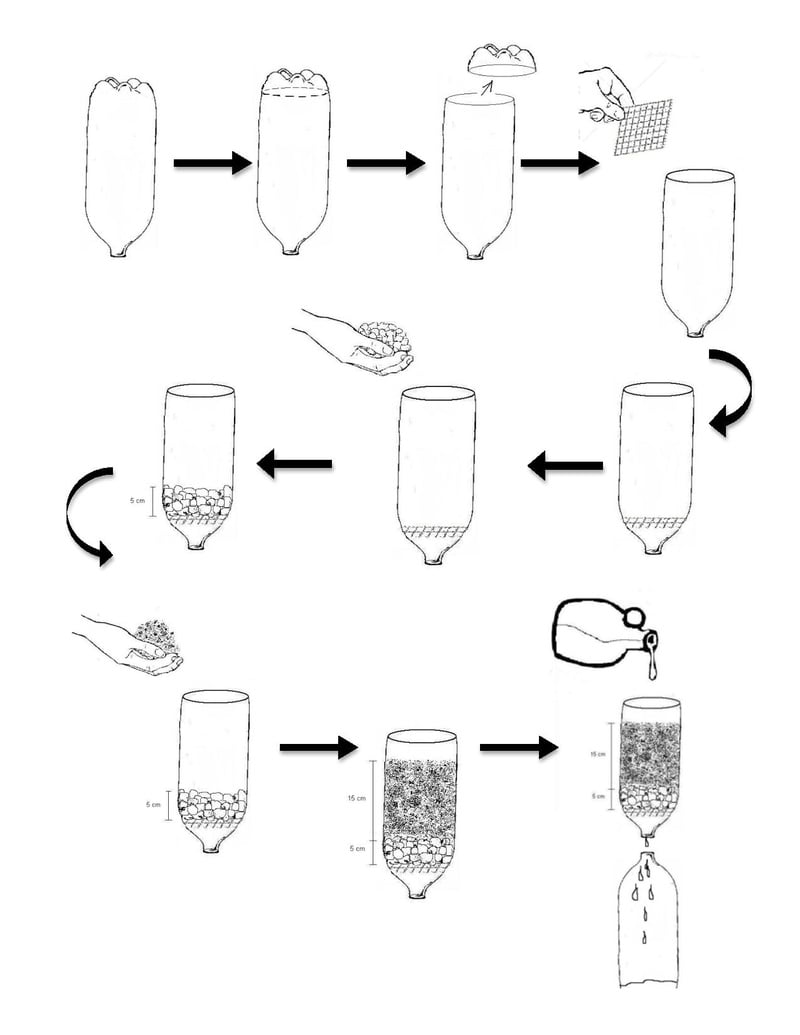

Materials needed[edit | edit source]

- One 2-L container (plastic beverage bottle or similar)

- One container for collection (plastic beverage bottle or similar)

- At least one clear PET plastic or glass beverage bottle, or plastic bag

- Approximately 2 kg (4.4 lbs) of well-graded sand or silty sand (particles cannot be uniform in size)

- Approximately 615 g (1.4 lbs) of gravel

- Piece of mesh screen, any material

- Any sharp blade

Assembly[edit | edit source]

A single-page, printable illustrated version of instructions can be found here:

How it works[edit | edit source]

As source water is poured into the filter, it will trickle down through the sand and gravel and come out the neck of the bottle. As it moves through the filter, the fine particles in the sand pass through with the water, taking with them the particles in the source water. The initial effluent will therefore be very dark and turbid, as it contains both the initial turbid source water as well as fines from the filter media. From here, the effluent settles to produce a very clear supernatant. This will be poured directly into the third bottle - the clear PET plastic or glass container - with care taken to ensure that the settled particles do not transfer. This relatively clear water can then be treated with the solar disinfection method with increased effectiveness as compared to unfiltered, unsettled water.

It is important that filtration occurs prior to settling in order to increase the quality of the supernatant. By passing through the filter media, the light particles in the source water are forced down by the larger, denser particles in the sand. If filtering does not occur first, the light particles in the source water will take an impractical amount of time to settle.

The specific mechanisms by which settling occurs in this case must be determined - refer to the 'Recommendations' section below for a discussion of the possible scientific principles at work, and how they may be used to optimize the design.

Treatment process[edit | edit source]

The following process, if followed correctly, should result in clear, microbial free water that is safe for drinking. In this method, turbidity is reduced by a combination of filtering and settling. Small particles in the source water pass through the filter with the small fines contained in the filter media. The particles in the source water are then forced to settle by the relatively larger, denser sand fines. The supernatant that is left once the particles have sufficiently settled should be clear enough to be effectively treated with the SODIS method, provided sufficient temperatures have been achieved for enough time.

- Removal of turbidity

- Pour untreated water through the filter media and collect in a container

- Allow this collected effluent to settle - this may take up to 1 day

- Once settling has sufficiently occurred, pour the clear supernatant into the clear PET plastic or glass bottle, or clear plastic bag. Do not yet put a cap or lid on it.

- Aeration pre-treatment:

- Agitate/swirl the bottle for several minutes in contact with the air.

- Removal of microbial organisms using SODIS

- Secure a cap or lid on the bottle and place in the sunlight for 6 hours. This part of the process can be optimized by placing the bottle on a dark surface or by painting one side of the bottle black (dark side facing down).

Complete, illustrated instructions for the SODIS-specific part of the treatment can be found here.

Cost and availability of materials[edit | edit source]

This filter system has the potential to be assembled at no cost to the user:

- The plastic and/or glass bottles can be sourced from the street as recycled material or from a landfill.

- The sand can be sourced from the land provided it is of suitable type (well-graded sand or silty sand)

If the sand cannot be readily sourced then this system should not be considered for use in that area, as it is not practical (and often not possible) for many individuals to import the required material. However, most well-graded sands and silty sands (that is, the contains grain sizes that range from fine to relatively coarse) should be effective, making this system suitable to any region with this type of sand.

ALTERNATIVE MATERIALS:

While the suggested design utilizes three plastic bottles, it is imperative that only one of these is a clear PET or glass bottle, or clear plastic bag. The other two containers (used to construct the filter and collect the filtrate) do not have to be plastic and in fact, any container of similar dimensions to what is suggested should be effective.

It should be noted that the clear container that contains the water to be treated with SODIS need not be 2 L in volume; in fact, the shallower the water, the faster SODIS treatment will take place. This is because the smaller volume of water will heat up more quickly and provides a shorter distance through which UV rays must pass to come in contact with all of the microbes.

Limitations[edit | edit source]

There are three critical limitations to this design: the availability of materials, the number of times the filter can be used effectively, and the time it collectively takes for particles collected in the effluent to settle and for solar disinfection to come to completion.

Materials[edit | edit source]

The sand must be well-graded, containing both fine and coarse particles. This makes the use of this filter unsuitable in areas that contain only poorly-graded sand (that is, sand that contains uniformly sized particles). This is certainly a restricting requirement. To that end, further research should be conducted into the use of ballasted flocculation to promote the settling of particles in turbid water, which could have far-reaching applications.

The water that is to be treated via solar disinfection must be contained in clear PET plastic or glass bottles, or a clear plastic bag. If these materials are not available in an area then this method cannot effectively be applied in its current form.

Filter life[edit | edit source]

Bench scale testing has shown that the filter can only be used twice with efficiency, as further trials resulted in a collected filtrate that would not easily settle. As the settling of the particles that cause the water to be turbid is essential to the function of this system, this is a considerable limitation. In its current form, the filter media will have to be replaced after every couple of uses, which the user may not find practical. Again, ballasted flocculation should be investigated as a means of inducing the settling of particles, thereby extending the life of the filter.

Time[edit | edit source]

Based on the observed settling period of around 1 day in the bench scale tests discussed below, the system may not be accepted by the end user, who may deem it to be impractical. The physical field test showed acceptable settling after 18 hours. If the settling time can be optimized, there is huge potential for this to be an effective means of consistently providing clean drinking water.

Furthermore, for solar disinfection to come to completion, the water must be exposed to direct sunlight for a period of several hours: 6 hours is recommended as a general guideline and longer time is required in overcast weather. This presents challenges to having this method utilized by the average household, whose members may not want to wait that long for the process to be completed.

Collection and storage considerations[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown that regardless of whether or not collected water is initially of acceptable microbiological quality, it often becomes contaminated during transport and storage due to unhygienic storage and handling practices.[1] Containers with narrow openings for filling, and dispensing devices such as spouts or taps protect the collected water during storage and use. According to the World Health Organization, "Other appropriate containers for safe storage are those in which water can be directly treated by the physical method of solar radiation and then directly stored and dispensed for household use. These improved containers protect stored household water from the introduction of microbial contaminants via contact with hands, dippers, other fecally contaminated vehicles or the intrusion of vectors."[1]The system suggested above follows these guidelines provided by the WHO. The filtering and settling processes involve a low level of handling and transportation prior to SODIS treatment, and there is almost no handling after SODIS treatment - the microbiologically treated water can be dispensed directly from the container in which it was treated. The absence of a need for a dipper or other handling device minimizes the risk for recontamination of the treated water.

Supporting research: experimentation and results[edit | edit source]

There exists extensive peer-reviewed literature regarding the use of sand filters as a means of reducing turbidity, as well as total suspended solids (TSS) and total dissolved solids (TDS). The mechanism by which turbidity is decreased varies among tests but the end results have shown similar effectiveness.

Ahmad and El-Dessouky found that turbidity in a sample of waste water effluent from a laundry facility in Pakistan decreased from 10.27 NTU to 2.4 NTU. The waste waster was filtered through three layers of filter media: sand of size 0.00125 m diameter, overlain by gravel of size 0.0125 m in the middle and then gravel of 0.025 m at the top. All three layers were of equal thickness (0.10 m) and the diameter of the filter was 0.2 m.[7] This filter functioned by retaining particles within the media.

Emerick et. al investigated two types of filter media in shallow circular sand filters (0.38 m deep, 1.2 m in diameter). The two media tested were medium-size coarse sand and crushed glass, with effective sizes ranging from 0.44mm to 3.3mm. Average removal rates of >94% and >96% were achieved for turbidity and TSS, respectively, regardless of medium characteristics.[8] This filter also functioned by retaining particles within the media.

An experiment was conducted in April 2010 to investigate the effectiveness of three different types of sand filters in reducing initial turbidity of water. The experimental process was designed to model as accurately as possible the conditions expected in the field, versus strictly controlled laboratory experimentation. The experiment was conducted by a fourth-year undergraduate civil engineering student at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. The full experiment, including materials, methodology, and results can be found here:. This filter functioned by adding fines contained within the media to the water as it passed through the filter. Solids within the water were then forced to settle by the relatively larger sand particles. This lends support to the use of sand in ballasted flocculation as a means of facilitating the settling of solids.

The results of this experiment, with the support of peer-reviewed literature, determined the design of the filter unit presented above, which was tested and showed similar qualitative results to bench scale testing.

Recommendations for further study[edit | edit source]

It has yet to be determined which settling mechanisms are at work in this design. One of two types of particle settling may be at work: Type I (discrete particle settling), or Type II (flocculating particle settling). In Type I settling, particle size, shape and density do not change with time but rather, stay as independent bodies - particle settling velocity remains constant. In Type II settling, particles coalesce with other particles and change in size, shape and density as they move downwards - as a result, the particle settling velocity also changes.[9] If Type I is the case, then the settling of the clay particles must be induced by the settling of the larger, denser sand particles, but each remains discrete. If Type II is at work, then particle flocculation would be due to the negative charge of the clay particles being attracted to the positive charge of the larger sand particles. It is likely that settling in this case occurred according to Type II.

For Type I settling, the terminal settling velocity of discrete particles in a column of water is given by the Stokes Equation:

where g is acceleration due to gravity; and are particle and water density, respectively; d is particle diameter, and is fluid viscosity.

The mass fraction of particles remaining with settling velocity , where is the column depth and is the time step is:

where is the concentration of particles in a sample of water drawn off at that time and is the initial concentration of particles.

Optimization of settling based on Type I settling occurs by analyzing the terminal settling velocity of the particles and designing a settling basin of idealized geometry to remove particles of a given size. In this case this is not practical, as the design settling column - i.e., effluent collection container - would be governed by the discrete particle settling velocity, which would therefore limit which materials could be used.

The more likely Type II settling occurs similarly, but analysis of settling velocity must be adjusted to account for the change in particle size and density as it flows downwards. Once this is done, settling time can be reduced by determining the optimal concentration of sand particles relative to clay particles required to cause settling.

While the bench tests showed promising results and the related physical model reflected those results, further testing should be conducted to validate the observations. Turbidity readings should be taken at intervals until a minimum time requirement for optimum settling is determined in both bench tests and physical model testing. Furthermore, methods to increase the rate of settling of particles in the filter effluent should be explored to decrease the time required to achieve acceptable turbidity. It may be found that using the filter media in this specific manner may not be necessary. In its current form, this method of reducing turbidity is very effective but not necessarily practical for all end users, placing a strong limitation on this design.

References and Links[edit | edit source]

SODIS official website: http://www.sodis.ch/index

World Health Organization: http://www.who.int/en/

World Health Organization link to full water sanitation document: Water in the Home: Accelerated Health Gains from Improved Water Supply

United Nations: http://web.archive.org/web/20210201182259/https://www.un.org/en/

Waterborne disease information: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waterborne_diseases, http://www.lenntech.com/library/diseases/diseases/waterborne-diseases.htm

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 World Health Organization, "Managing Water in the Home: Accelerated Health Gains from Improved Water Supply", 2002.

- ↑ Lenntech Water Treatment Solutions, "Waterborne Diseases", <http://www.lenntech.com/library/diseases/diseases/waterborne-diseases.htm>, Accessed April 4, 2010.

- ↑ G.K. Rijal, R.S. Fujioka, "Synergistic effect of solar radiation and solar heating to disinfect drinking water sources." Water Science Technology, 43 (12):155-162, 2001.

- ↑ R.H. Reed, "Solar inactivation of faecal bacteria in water: the critical role of oxygen." Letters of Applied Microbiology, (24) 276-280, 1997.

- ↑ Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, "SODIS Method", <http://web.archive.org/web/20200129161417/http://www.sodis.ch:80/methode/anwendung/index_EN>, Accessed April 8, 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 B. Sommer et. al, "SODIS - an emerging water treatment process", Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology - AQUA, (46)3, 127-137, 1997."

- ↑ J. Ahmad, H. EL-Dessouky, "Design of a modified low cost treatment system for the recycling and reuse of laundry waste water", Resources, Conservation and Recycling (52), 973–978, 2008.

- ↑ R.W. Emerick et. al, "Shallow intermittent sand filtration: Microorganisms removal", Small Flows Journal, (3)1, 12-22, 1997.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 R.H. Droste, Theory and Practice of Water and Wastewater Treatment, John Wily & Sons, Toronto, 1997.