The use of clay in folk medicine goes back to prehistoric times. The indigenous peoples around the world still use it widely, which is related to geophagy. The first recorded use of medicinal clay goes back to ancient Mesopotamia. A wide variety of clays is being used for medicinal purposes - primarily for external applications, such as the clay baths in health spas (mud therapy), but also internally. Modern scientific research has backed up the healing powers of clay. Among the clays most commonly used for medicinal purposes are the smectite clays such as Bentonite, Montmorillonite, and Fuller's Earth, and also kaolin.

Questions of nomenclature

There are considerable problems with the exact nomenclature of various clays. No clay deposit is exactly the same and, typically, mineral clays are mixed in various proportions.

Overwhelming majority of clay mined commercially is for a wide variety of industrial uses, such as in construction, and oil drilling. Thus, the precise classification and chemical composition of these clays are somewhat secondary to their intended use. For practical purposes, the terms "Bentonite clay", "Montmorillonite clay", and "Fuller's Earth" are basically interchangeable. As readily admitted in literature, the precise definition of these terms is lacking.

On the other hand, the clays that are typically used for medicinal purposes have usually been discovered either based on local folklore, or by simple trial-and-error after investigations by various healing enthusiasts. And so, their discoverers may have been either not too concerned about these clays' precise scientific classification and chemical properties, or perhaps not necessarily adequately equipped to conduct such studies. Their primary, and often only, concern was the efficacy of any particular clay for some specific medical condition or conditions.

"Sodium Bentonite" is the most commonly used medicinal clay today, although there is no precise definition of what this term means. In fact, typically, "Bentonite" refers to a wide spectrum of clays with a wide array of properties (such as a variety of colours). In alternative medicine, often this is used as more or less a catch-all term for medicinal clays. Another such term is "Montmorillonite", which is often interchangeable with "Bentonite". Bentonite is included in the United States Pharmacopeia, and the USP-grade Bentonite is widely used in various pharmaceutical and cosmetic preparations as a compounding and suspending agent. It is not entirely clear where the source of USP-grade Bentonite is located; it may be a mixture of various Bentonites.

Self-healing by animals

A relevant subject is how the animals - both in the wild and domesticated - seek out and consume different types of earth in general, and clay in particular (of course clay is pretty well omnipresent in variouis types of soil).

Galen, the famous Greek philosopher and physician, was the first to record the use of clay by sick or injured animals back in the second century AD. This type of geophagy has been documented in "many species of mammals, birds, reptiles, butterflies and isopods, especially among herbivores."[1]

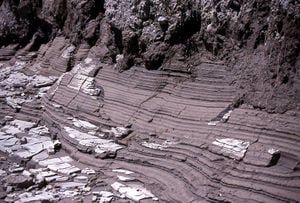

In particular, in Peru, Amazonian rainforest parrots of some 21 species gather at certain sites on cliff faces where bare soil is exposed, and eat the clayish soil. The soil they seek is highly specific, since they focus on a rather narrow band of exposed soil. What they seek is mostly clay that is less than 0.2 millimetre in particle diameter.

See also animal geophagy.

Historical use

There is a large amount of anthropological and historical literature describing the medicinal use of clay around the world from the earliest times.

Human prehistory

Some scholars believe that prehistoric ancestors such as Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis used ochres to cure wounds as well as paint caves. Ochres are a mixture of clay and iron hydroxides.

"The oldest evidence of geophagy practiced by humans comes from the prehistoric site at Kalambo Falls on the border between Zambia and Tanzania (Root-Bernstein & Root-Bernstein, 2000)." Here, a calcium-rich white clay was found alongside the bones of Homo habilis (the immediate predecessor of Homo sapiens).[2]

Use by aboriginal peoples

Clay is used widely by indigenous peoples around the world, and is related to geophagy.

The Pomo Indians of California learned to consume bitter, and somewhat toxic acorns that grow in their area by mixing them with clay. They baked dry acorn flour with small amounts of powdered red clay. This mixture was then baked into bread, which was one of their main staples.[3] The clay reduced the bitterness of the acorns, and absorbed some of their toxins.

The same type of clay use has been reported among the indigenous peoples in the Andes Mountains of South America. A type of a local wild potato contains bitter alkaloids, so the native peoples learned to cook these bitter potatoes with clay, which made them edible.[4]

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

The first recorded use of medicinal clay is on Mesopotamian clay tablets around 2500 B.C. Also, ancient Egyptians used clay.[5]

In Egypt, Cleopatra used clays to preserve her complexion. But the Pharaohs’ physicians used the material as anti-inflammatory agents and antiseptics. It was also an ingredient used for making mummies.[6]

Classical times

Lemnian clay

This was the most famous clay in Classical Antiquity. Mined on the island of Lemnos, the fame of this reddish clay spread far and wide. In fact, Lemnian clay appears to have been in continuous use from the earliest antiquity to modern times. Its use continued until the 19th century, as it was still listed in an important pharmacopoeia in 1848[7] (the deposits may have been exhausted by then).

According to legend, during the Trojan war, the hero Philoctetes was stranded on Lemnos with a sick foot giving off unbearable stench (there are different versions of what may have caused the wound). He was said to have been healed by an application of the Lemnian Earth.

As Pliny reports about the Lemnian Earth:

"...if rubbed under the eyes, it moderates pain and watering from the same, and prevents the flow from the lachrymal ducts. In cases of haemorrhage it should be administered with vinegar. It is used against complaints of the spleen and kidneys, copious menstruation, also against poisons, and wounds caused by serpents."

Lemnian clay was shaped into tablets, or little cakes, and then distinctive seals were stamped into them, giving rise to its name terra sigillata - Latin for 'sealed earth'. Dioscorides also commented upon the use of terra sigillata.[8]

Another physician famous in antiquity, Galen, recorded numerous cases of the internal and external uses of this clay in his treatise on clay therapy.

"Galen... used as one of his means for curing injuries, festering wounds, and inflammations terra sigillata, a medicinal red clay compressed into round cakes and stamped with the image of the goddess Diana. This clay, which came from the island of Lemnos, was known throughout the classical world."[9]

Clay was prescribed by the Roman obstetrician, gynecologist, and pediatrician Soranus of Ephesus, who practiced medicine around 100-140 AD.

Other clays used in classical times

The other types of clay that were famous in antiquity were as follows.

- Terra chia, Terra cymolia (Cimolean earth): these were both white earths and considered of great value.

- Samian earth: Pliny in c. 50 AD (Nat. Hist.) details two distinct varieties, colyrium - an eye salve, and aster, which was used as a soap as well as in medicines.

- Terra sigillata strigoniensis (Strigian earth, derived from Silesia) - this clay, yellow in colour, appears to have been famous later in medieval times.

All the above seem to have been bentonitic clays.

- The earth which did not stain the hands was known as rubrica.

Medieval times

In medieval Persia, Avicenna (980-1037 CE), the 'Prince of Doctors', wrote about clay therapy in his numerous treatises.

Ibn al-Baitar (1197-1248), an Arabic scholar born at Malaga, Spain, and author of a famous work on pharmacology, discusses eight kinds of medicinal earth.[10] The eight kinds are:

- the terra sigillata,

- Egyptian earth,

- Samian earth,

- earth of Chios,

- Cimolean earth or pure clay (cimolite), soft earth, called al-hurr, green in color like verdigris, is smoked together with almond bark to serve as food when it will turn red and assume a good flavor; it is but rarely eaten without being smoked - also called 'Argentiera',

- earth of vines called ampelitis (Pliny XXXV, 56) or pharmakitis from Seleucia in Syria,

- Armenian earth, salutary in cases of bubonic plague, being administered both externally and internally,

- earth of Nishapur.[11]

Renaissance period, and up to the present

A French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517‑1564) was interested in investigating the mystery of the Lemnian clay. In 1543, he visited Constantinople where, after making enquiries, he encountered 18 types of different products marketed as Lemnian Earth (he was concerned about possible counterfeits). He then made a special journey to Lemnos, where he continued his investigation, and tried to find the source of the clay. He discovered that it was extracted only once a year (on the 6th of August) under the supervision of Christian monks and Turkish officials.

Modern investigation has shown that this was a clay similar to the modern 'bentonite'.

Preparation of clay

Clay gathered from its original source deposit is refined and processed in various ways by manufacturers. This can include heating or baking the clay. Some practitioners insist that raw clay (as close to its original state as possible) has the best therapeutic effect.[12] This is because the raw clay also tends to contain a variety of micro-organisms that may contribute to healing."[13] Heating the clay may destroy those micro-organisms.

Too much processing, likewise, may reduce the clay's therapeutic potential. In particular, Mascolo et al. studied 'pharmaceutical grade clay' versus 'the natural and the commercial herbalist clay', and found an appreciable depletion of trace elements in the pharmaceutical grade clay.[14] On the other hand, certain clays are typically heated or cooked before use.[15]

Medicinal clay is typically available in health food stores as a dry powder, or in jars in its liquid hydrated state - which is convenient for internal use. For external use, the clay may be added to the bath, or prepared in wet packs or poultices for application to specific parts of the body. Often, warm packs are prepared; the heat opens up the pores of the skin, and helps the interaction of the clay with the body.[16]

In the European health spas, the clay is prepared for use in a multitude of ways - depending on the traditions of a particular spa; typically it is mixed with peat and matured in special pools for a few months or even up to two years.

"The majority of spas ... use artificial ponds where the natural ("virgin") clay is mixed with mineral, thermo-mineral, or sea water that issues in the vicinity of the spas or inside the spa buildings."[17]

Medicinal properties of clay in modern research

Absorptive and adsorptive properties of clays

Absorption

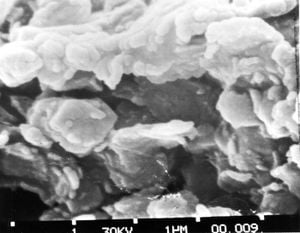

Clay demonstrates its absorptive properties by acting like a sponge; it draws various toxic substances into its internal multi-layered structure. The clay expands as the absorbed substance fills the spaces between its stacked silicate layers.

Adsorption

The clay's mineral surfaces are negatively charged (i.e. they possess negative electrical charges), which attracts the positively charged toxins, such as the heavy metal ions. An exchange reaction then occurs; the clay swaps its ions for the heavy metal ions.

Detoxifying properties

The above processes contribute to the detoxifying properties that the medicinal clays exhibit. Also, see below.

Antibacterial properties

In a recent article in The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Haydel et al. studied iron-rich smectite and illite clay (Montmorillonite/Bentonite type of clay), and found that it was effective in killing bacteria in vitro.[18] Authors report that the clay mineral,

"...exhibits bactericidal activity against E. coli, ESBL [Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases] E. coli, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and M. marinum, and significantly reduces growth of S. aureus, PRSA, MRSA, and nonpathogenic M. smegmatis approximately 1,000-fold compared to cultures grown without added mineral products."[19]

In a more recent study funded by the National Institutes of Health, Williams, Haydel, et al. collected more than 20 different clay samples from around the world, including the bentonite-type clays, to investigate their antibacterial activities.[20] The authors report that they have achieved promising results against MRSA superbug infections and disease. Also, see below.

Trace minerals

Clays contain massive amounts of trace minerals, necessary for good health. (It is common to see 60 different trace minerals and more in various clays.) This may explain many of the healing properties of clay. Specific trace minerals that various clays possess vary very widely. Also, the amount of any particular trace mineral in any specific clay varies a lot among different clays. For example, the amount of iron in various bentonite clays can vary from well below 1%, and up to 10%.

External use

Mud baths

This is perhaps the most common use of clay. Just about all health spas around the world use clay on a daily basis, and report many health benefits for bathers. See mud baths.

Skin infections

Many types of skin infections have been healed by the application of medicinal clay. Clay is used in many over the counter medicines for this purpose.

Buruli ulcer

This flesh-eating bacterial disease is found primarily in central and western Africa.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has described Buruli ulcer as "an emerging public health threat". The disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans - which is related to the micro-organisms that also cause leprosy and tuberculosis. This bacterium produces a powerful toxin that causes necrotic lesions, and destroys the fatty tissues under the skin.

The toxin produced by the bacteria suppresses the immune system, so patients feel no pain, and there is no response from the body to the infection. The disease is quite similar to leprosy. The commonly accepted treatments, which include antibiotics and surgical intervention, have not been very effective.

(Antibiotics currently play little part in the treatment of this disease. Surgical excision can be effective if undertaken early, yet it leaves scars, and can be dangerous. Advanced disease may require prolonged treatment with extensive skin grafting. Thus, such treatment is expensive, and may be difficult to obtain in third world conditions.)

Two French medicinal clays have shown some remarkable results against this disease. Dr Lynda Williams and Dr Shelley Haydel of Arizona State University have been studying the effectiveness of these French green clays, which are mostly composed of minerals called smectite and illite. These clays exhibit significant antibacterial properties.[21]

Use in bandages

In April 2008, the Naval Medical Research Center announced the successful use of a Kaolinite-derived aluminosilicate nanoparticles infusion in traditional gauze known commercially as "QuikClot Combat Gauze".[22]

Internal use

According to one theory,

"In the stomach, the negative electrical charges of tiny clay particles attract positively charged toxins from stomach fluids. This clumping prevents very small particles, such as toxic molecules, from passing through the walls of the intestines and entering the bloodstream."[23]

The author notes further that, together with the clay, the toxins are then eliminated harmlessly out of the body through the kidneys or bowel.

There are many over the counter remedies for internal use that contain clay. The examples are the tablets such as Kaopectate (Upjohn), Rheaban (Leeming Div., Pfizer), and Diar-Aid (Thompson Medical Co.). The labels on all of these showed the active ingredient to be Attapulgite, each tablet containing 600 (or 750 mg) of this component along with inert materials or adjuvants.[24]

Numerous medicines also use Kaolinite clay, which has long been a traditional remedy to soothe an upset stomach. Also, Kaolin is or has been used as the active substance in liquid anti-diarrhea medicines such as Kaomagma. Such medicines were changed away from aluminium substances due to a scare over Alzheimer's disease, but have since changed back to compounds containing aluminium as they are most effective.

Anti-diarrheal properties

In addition to the above clays, also Diosmectite clay is valued in medicine for its anti-diarrheal effects. Diosmectite is a type of a smectite clay. It is described as a natural silicate of aluminium and magnesium, so it is magnesium-rich. It has strong adsorbent properties, so it's used as an intestinal adsorbent in the treatment of several gastrointestinal diseases, including diarrhea. Basically, this seems to be another trade name for Bentonite-type clay.

According to a recent review article,

"Diosmectite reduces inflammation, modifies mucus rheologic properties, inhibits mucolysis, and adsorbs bacteria, bacterial enterotoxins, viruses and other potentially diarrheogenic substances."[25]

The same authors cite a number of studies showing that diosmectite is effective against diarrhea in children with mild-to-moderate acute symptoms. It reduces the duration of illness, and decreases the frequency of bowel motions after 2 days of treatment. No serious adverse effects have been observed.

In 2001, an Italian study examined the anti-diarrheal effects of a clay described as 'smectite', and also found positive results.[26] The authors conclude that "smectite reduces the duration of diarrhea and prevents a prolonged course." They also note that smectite clay increases intestinal barrier function.

Candida

Clays have proven to be effective against the Candida albicans infections. This is a type of a fungus (or yeast), which is a causal agent of opportunistic oral and genital infections. This type of infection, known as Candidiasis, also may enter the bloodstream, and become a systemic Candida infection.

In 1971, the influence of bentonite clay on the growth of Candida lipolytica has been studied by Maignan and Pareilleux. A clearly unfavorable effect of bentonite on Candida lipolytica growth was observed [27]

Later on, the same authors have concluded that,

"The respiration of Candida lipolytica on n-tetradecane is decreased in the presence of bentonite."[28]

According to a 2009 study by Ghiaci et al., bentonite clay acts very strongly against Candida:

"The modified bentonite with monolayer surfactant (BMS), was the best support, for immobilization."[29]

Heavy metal chelation

Chelation (purging) of heavy metals from the body has been a very effective way to treat many illnesses. Chelation therapy is the use of chelating agents to detoxify poisonous metal agents such as mercury, arsenic, and lead by converting them to a chemically inert form that can be excreted without further interaction with the body, and has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1991.

Clay has proven to be a very effective chelating agent.

Oyanedel-Craver and Smith have studied sorption of four heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Zn and Hg) to 3 kinds of bentonite clay. The overall conclusion of the study was that the organoclays studied have considerable capacity for heavy metal sorption.[30]

Irritable bowel syndrome

"[B]eidellitic montmorillonite is efficient for C-IBS patients (suffering from constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome)..."[31]

Aflatoxicosis

Aflatoxins are naturally occurring mycotoxins that are produced by many species of Aspergillus, a fungus. Aflatoxins are toxic and among the most carcinogenic substances known. They cause Aflatoxicosis, which can afflict both animals and humans.

Bentonite clay has proven to show a very strong protective effect against Aflatoxicosis.

"The addition of bentonite or HSCAS [hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate] to the AF-contaminated diet diminished most of the deleterious effects of the aflatoxin. Pathological examinations of liver and kidney proved that both bentonite and HSCAS were hepatonephroprotective agents against aflatoxicosis."[32]

Also,

"The addition of sodium bentonite was significantly effective in ameliorating the negative effect of aflatoxicosis on the percentage and mean of phagocytosis."[33]

Use during pregnancy

Pregnant women in many indigenous and traditional cultures very commonly consume clay, especially to reduce nausea. Since clays contain a very large amount of trace minerals of all sorts, this most likely contributes to the development of a healthy foetus.

Scientific analyses of clays selected by pregnant women in Nigeria show that eating as little as 500 mg (about the equivalent of two Tylenol capsules) per day can satisfy nearly 80 percent of a pregnant woman's calcium needs.[34]

Use by the NASA Space Program

The effects of weightlessness on human body were studied by NASA back in the 1960s. Experiments demonstrated that weightlessness leads to a rapid bone depletion, so various remedies were sought to counter that. A number of pharmaceutical companies were asked to develop calcium supplements, but apparently none of them were as effective as clay. The special clay that was used in this case was Terramin, a reddish clay found in California. Dr. Benjamin Ershoff of the California Polytechnic Institute demonstrated that the consumption of clay counters the effects of weightlessness. He reported that "the calcium in clay ...is absorbed more efficiently ... [clay] contains some factor or factors other than calcium which promotes improved calcium utilization and/or bone formation." He added, "Little or no benefit was noted when calcium alone was added to the diet."[35]

Most commonly used medicinal clays

Bentonite-type clay has been used to treat infections, indigestion, and other medical problems by both applying wet clay topically to the skin as a poultice, and by ingesting it.

Bentonite has been prescribed as a bulk laxative, and it is also used as a base for many dermatologic formulas.[36] Dermatologically, it is used as part of a treatment for pruritis.[37] Also, Bentonite can be used as a therapeutic face pack for the treatment of acne/oily skin. Clearasil, an acne cream, uses bentonite as an agent to absorb excess sebum, clearing pores.

Very similar to Bentonite.

It is a very absorbent clay, somewhat similar to bentonite. When used in medicine, it physically binds to acids and toxic substances in the stomach and digestive tract. For this reason, it has been used in several anti-diarrheal medications,

This type of clay is not as absorbent as most clays used medicinally (it has a low shrink-swell capacity). Also, it has a low cation exchange capacity. This clay is also known as 'white cosmetic clay'. Clay, in the form of kaolin, is still a common ingredient in western medicines such as Rolaids and Maalox, as well as in cosmetics.

This is a clay used industrially, but it is also used in medicine, such as against paraquat poisoning.

- French Green Clay

There are many kinds of French Green Clay. They are typically described as 'Montmorillonite' clays. Two well known traditional brands are 'Argiletz', and 'Agricur'.

- Pascalite (a variety of bentonite).

It was first identified by a miner named John Pascal. Apparently, this clay is very rich in silica.

- Terramin

A reddish clay from California, used by Native Americans. It is typically described as 'Bentonite'.

- Rhassoul clay

A light brown clay from Morocco that is especially good for mature skin. It is used to draw out toxins, moisturizing, and returning elasticity to the skin. It can be used on all skin types.

- The Peruvian Fango mud.

It is used in cosmetics

- Jordan clay

- Redmond Clay

A whitish clay from Utah.

See also

- Peloid - use of clay in therapeutic baths.

The following earth minerals are also used as dietary supplements, as well as in agriculture as feed supplements.

Notes

- ↑ Jared M. Diamond, "Evolutionary biology: Dirty eating for healthy living". Nature 400, 120-121 (1999)

- ↑ Olle Selinus, B. J. Alloway, Essentials of medical geology: impacts of the natural environment on public health. Academic Press, 2005 ISBN 0126363412, p. 446

- ↑ The Indian tribes of North America- by Magdalena Antonczyk (accessed 22 May 09)

- ↑ Science Stories

- ↑ ASU research

- ↑ ASU research

- ↑ Olle Selinus, B. J. Alloway, Essentials of medical geology: impacts of the natural environment on public health. Academic Press, 2005 ISBN 0126363412, p. 446

- ↑ Olle Selinus, B. J. Alloway, Essentials of medical geology: impacts of the natural environment on public health. Academic Press, 2005 ISBN 0126363412, p. 446

- ↑ Dr. H. Van Der Loos, The Miracles of Jesus, Leiden, the Netherlands, Brill, 1965. p. 82.

- ↑ L. Leclerc, "Traite des simples", II, 1881, pp. 421-427; for a general appreciation of this work see Baron Carra de Vaux, "Les penseurs de lslam", II, 1921, pp. 289-296 (original note in Laufer)

- ↑ Laufer, Berthold, "Geophagy". Chicago: Field Museum Press, 1930. (available online)

- ↑ "For clay baths, the experts agree that clean, raw, natural swelling smectite clays are the best. This includes swelling bentonites and montmorillonites." from Aboutclay.com website (accessed 16 June 2009)

- ↑ "Soil, including kaolinitic and montmorillonitic clays, contains considerable amounts of organic material, including many live microorganisms." from CDC.gov websiteCallahan GN. Eating dirt. Emerg Infect Dis [serial online] 2003 Aug. (accessed 16 June 2009)

- ↑ "The pharmaceutical clay shows an appreciable depletion of elements as Zn, V, Ga, Cr, Cd, Fe, Mo, Ni, Cu, Sb, S and Rb. Instead, the natural clay is characterised by high quantities of U, V, Cd, Mo, Tl, Ag, Ni, Cu, Sb, As, S, Se and Br, likely because of sulphide occurrence." -- Nicola Mascolo, Vito Summa, F. Tateo, Characterization of toxic elements in clays for human healing use. Applied Clay Science, Volume 15, Issues 5-6, 1999 doi:10.1016/S0169-1317(99)00037-X

- ↑ An example of this is the medieval 'Argentiera' clay, mentioned in this article.

- ↑ "Hot application is recommended in geotherapy, pelotherapy or paramuds in beauty therapy..." Carretaro MI, Gomes CSF, Tateo F. "Clays and human health." In: Bergaya F, Theng BKG, Lagaly G, editors. Handbook of Clay Science, Developments in Clay Science. Vol. 1. Elsevier Ltd; Amsterdam: 2006. pp. 717–741. ISBN 0080441831 p. 723

- ↑ Carretaro MI, Gomes CSF, Tateo F. "Clays and human health." In: Bergaya F, Theng BKG, Lagaly G, editors. Handbook of Clay Science, Developments in Clay Science. Vol. 1. Elsevier Ltd; Amsterdam: 2006. pp. 717–741. ISBN 0080441831, ISBN 9780080441832 p. 724

- ↑ Dec 10, 2007. Broad-spectrum in vitro antibacterial activities of clay minerals against antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens (accessed 31 March 2009)

- ↑ full text of the article

- ↑ Apr 7, 2008. “Healing clays” hold promise in fight against MRSA superbug infections and disease. (accessed 31 March 2009)

- ↑ Margaret Coulombe, "Healing Clay" Arizona State University website

- ↑ Nanoparticles Help Gauze Stop Gushing Wounds

- ↑ Suzanne Ubick, "Mud, Mud, Glorious Mud", in California Wild, The Magazine of the California Academy of Sciences, 2005

- ↑ U.S. Patent 5079201

- ↑ Dupont, Christophe; Vernisse, Bernard, Anti-Diarrheal Effects of Diosmectite in the Treatment of Acute Diarrhea in Children: A Review. Pediatric Drugs: 1 April 2009 - Volume 11 - Issue 2 - pp 89-99 doi:10.2165/00148581-200911020-00001

- ↑ Guarino A, Bisceglia M, Castellucci G, Iacono G, Casali LG, Bruzzese E, Musetta A, Greco L, Smectite in the treatment of acute diarrhea: a nationwide randomized controlled study of the Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology (SIGEP) in collaboration with primary care pediatricians. SIGEP Study Group for Smectite in Acute Diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001 Jan;32(1):71-5. PMID 11176329

- ↑ Maignan C and Pareilleux A, Influence of bentonite on the growth of Candida lipolytica. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des seances de l'Academie des sciences. Serie D: Sciences naturelles 273(9):835-8, 1971 Aug 30

- ↑ Pareilleux A, Maignan C., Can J Microbiol. 1976 Aug;22(8):1065-71. [Metabolic activity of Candida lipolytica adsorbed to bentonite with hydrophobic chains] [Article in French]abstract and a link to full text

- ↑ M. Ghiaci, H. Aghaei, S. Soleimanian, M.E. Sedaghat S, "Enzyme immobilization: Part 1. Modified bentonite as a new and efficient support for immobilization of Candida rugosa lipase." Applied Clay Science, Volume 43, Issues 3-4, March 2009, Pages 289-295

- ↑ Oyanedel-Craver VA, Smith JA, "Effect of quaternary ammonium cation loading and pH on heavy metal sorption to Ca bentonite and two organobentonites". J Hazard Mater 2006; 137:1102-14.

- ↑ Ducrotte P, Dapoigny M, Bonaz B, Siproudhis L. "Symptomatic efficacy of beidellitic montmorillonite in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Feb 15;21(4):435-44. available online

- ↑ M A Abdel-Wahhab, S A Nada, I M Farag, N F Abbas, H A Amra, "Potential protective effect of HSCAS and bentonite against dietary aflatoxicosis in rat: with special reference to chromosomal aberrations." Nat Toxins - 1998 (Vol. 6, Issue 5, Pages 211-8)

- ↑ I. K. IBRAHIM, A. M. SHAREEF, K. M. T. AL-JOUBORY, "Ameliorative effects of sodium bentonite on phagocytosis and Newcastle disease antibody formation in broiler chickens during aflatoxicosis". Research in Veterinary Science, Volume 69, Issue 2, October 2000, Pages 119-122

- ↑ Suzanne Ubick, "Mud, Mud, Glorious Mud", in California Wild, The Magazine of the CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, 2005

- ↑ Suzanne Ubick, "Mud, Mud, Glorious Mud", in California Wild, The Magazine of the CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, 2005

- ↑ Bentonite from oregonstate.edu website

- ↑ Calamine from www.drugs.com website

References

- Johns T, Duquette M, "Detoxification and mineral supplementation as functions of geophagy." Am J Clin Nutr. 1991 Feb;53(2):448-56

- Ray E. Ferrell, Jr., MEDICINAL CLAY AND SPIRITUAL HEALING. Clays and Clay Minerals; December 2008; v. 56; no. 6; p. 751-760; DOI: 10.1346/CCMN.2008.0560613

- Lynda B. Williams, Shelley E. Haydel, Ray E. Ferrell, Jr., "Bentonite, Bandaids, and Borborygmi". Elements; April 2009; v. 5; no. 2; p. 99-104; DOI: 10.2113/gselements.5.2.99

External links

- "Parrots That Eat Dirt"- by Jack Myers

Bibliography

- Michel Abehsera, The healing clay : the centuries-old health & beauty elixir rediscovered. Brooklyn, N.Y. : Swan House, 1979. ISBN 0918282101 Template:OCLC (German and Spanish editions are also available.)

- Dr. Frederic Damrau, M.D., "The Bentonite Cure -- Cleanse Yourself Internally with Liquid Clay". Medical Annals of the District of Columbia, 1961

- Raymond Dextreit, "Our Earth, Our Cure"

- Raymond Dextreit, "Earth cures: A Handbook of Natural Medicine for Today"

- Dr. Cindy Engel, Wild Health: Lessons In Natural Wellness From The Animal Kingdom. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003. ISBN 0618340688

- Cano Graham, "The Clay Disciples"

- Wendell Hoffman, "Energy to Heal"

- Knishinsky, Ran. "The clay cure – natural healing from the earth". Healing Arts Press. 1998.

- Laufer, Berthold, "Geophagy". Chicago: Field Museum Press, 1930. (available online)

- PerryA, "Living Clay, Nature’s Own Miracle Cure"

- Price, Dr. Weston A. DDS. "Nutrition and physical degeneration. Keats Publishing". 1939. (266-267).

- W. Rudolph Reinbacher, "Healing earths: the third leg of medicine : a history of minerals in medicine with rare illustrations from 300 to 1000 years ago." Published by W. Rudolph Reinbacher, 2002

- Robert and Michele Root-Bernstein, "Honey, Mud, Maggots and Other Medical Marvels." Houghton Mifflin, 1997.