This is the research done for Las Malvinas botica popular fiber-crete 2013.

Climate[edit | edit source]

- Being located between the geographical coordinates 17 ° 30 and 19 ° 56 north latitude and 68 ° 19 and 72 ° 31 W, Dominican Republic is located in the tropical region. It has a very rugged relief, about 50% of its territory is occupied by five mountain ranges and three great mountain ranges, among which are the highest peaks of the Antilles (Pico Duarte 3,187 m).[1]

- The Dominican Republic, due to its geographical position, has a tropical climate that is regionally influenced by topography, trade winds, and atmospheric phenomena.[2]

Temperature[edit | edit source]

The Dominican Republic has an average annual temperature of about 25 °C (77 °F) which is defined as a warm tropical climate. The higher temperature, about 34 °C (93 °F), recorded in the months from June to August, and the lowest, 19 °C (66 °F), recorded between December and February.[3]

Precipitation[edit | edit source]

In the Dominican Republic there are three rainy seasons: Season Front (November-April), Convective Season (May-July) and hurricane season (August-October).[4]

Components[edit | edit source]

At the block-making site where we have been allowed to press our blocks, they use a mixture of sand, gravel, cement and water to make their blocks. For our blocks, we are replacing sand and gravel with other materials and in using rice hull ash and lime we hope to utilize less cement, making a cheaper and lighter block. The mixture used on-site that we are comparing to is 3 wheelbarrows of sand, 1 wheelbarrow of gravel, 1 bag of cement and 2 buckets of water, which makes around 33 blocks.[5]

Sand & Gravel[edit | edit source]

Cement is not enough to make a block by itself. Sand and gravel give blocks their structure, held together by cement "glue". In these experiments we are mostly replacing sand and gravel with our alternate materials.

Lime[edit | edit source]

- For this project, we will be using lime in several stages. It is an ingredient in the upcycled cinder blocks and plaster because of its ability to prevent water damage. Mg and CaO are the active ingredients in lime. While other components in the lime can be present, they are considered impurities in the mixture. Hydrated lime is expressed as CaO+H2O>Ca(OH)2, which is the powdered dry material often used in plasters.[6] The hydrated lime then needs to be rehydrated in a process called "slaking". The action of slaking lime is a process of adding water to the powdered lime mixture until the powder can not absorb any more water. The CaO is responsible for this behavior of absorption and reaches a limit which becomes obvious due to a layer of excess water on top of the lime slurry.[7]

- Lime can also be used as a component for mortars, plaster, and a final lime wash. Plasters can be applied to moistened surfaces, upon which you can apply a scratch coat followed by a final smooth coat. Lime wash is typically used as a final coat for plasters and composed of water, slaked lime and pigment if desired.[8]

- Important: Lime is very caustic, and therefore requires the use of protective gear when working with lime and water mixtures. The pH level can reach 12, which can damage the skin. Vinegar or lemon can be used to neutralize the lime if it comes in contact with the skin. As a precaution, it is suggested that you wear protective gear including rubber gloves, goggles and appropriate clothing.[9]

Block Making[edit | edit source]

The raw materials used in the creation of concrete blocks typically include sand, gravel, and cement, but can vary depending on purpose and available materials. These materials are kept separate and dry until ready for pressing. They are then consolidated by using large mixing blades and adding water until the desired texture is reached. The mixture is then placed into a mold in a large machine that applies high levels of pressure to the mixture. Four blocks are produced at a time by the machine used in Las Malvinas. The curing process requires that the drying process is controlled so that the blocks do not dry too quickly, which would result in cracking. This is controlled through watering down the blocks several times depending on local climate.[10]

Fiber-Cretes[edit | edit source]

A fellow student and past Practivista at UNIBE shared some of his current research from making blocks with sawdust and other materials. In his experimentation he is using sawdust as a replacement for river sand. This is a potential area for experimentation in this project. His blocks were very durable and able to withstand approximately 2,900 Newtons of force.[11]

Paper-Crete[edit | edit source]

- Papercrete is an alternative construction material that, in general, is made up of milled paper and an adhesion component like clay or cement. Since paper comes in many forms, i.e. junk mail, magazines, beer cartons, newspapers, etc., so does papercrete. While there is no definitive formula for building with papercrete, various forms of papercrete masonry have been successfully employed.[12] Paper is a common waste product and can be sourced for free, making papercrete an affordable, green masonry alternative. In Santo Domingo recycling services are not readily accessible and waste management is a visible environmental issue. The use of papercrete construction can be a paper-waste outlet for growing communities, while reducing the cost of building materials.

- In the 2012 Practavistas program, the Las Malvinas group worked on building a schoolroom out of papercrete and ecoladrillo. Their process involved pulping the paper with a blender in a mix of 4 parts paper to 1/8 part lime and 8 parts water, then letting the mixture dry. This was then mixed with concrete and water and the slurry was pressed into blocks. The ratios for these blocks were 1 part paper to 1 part sand and 1 part cement..[13] In a visit to the site this summer, the papercrete wall in the schoolroom appeared to be in very good condition, better, in fact, than the ecoladrillo.

Properties[edit | edit source]

- In terms of insulation, papercrete has an R-value between 2.0 and 3.0, making it a more suitable building material than concrete for the Dominican Republic's warm climate. The R-value of concrete is about 0.08.[14]

- Papercrete can have a compressive strength of about 150 lbs per square inch, much lower than concrete but enough to support a roof load.[15] Papercrete blocks tested at this amount of pressure squished, but did not crumble.

Recipes[edit | edit source]

- Here is a starting formula provided by LivingInPaper.com for a 200-gallon batch:[16]

- 160 gallons (727 liters) of water

- 60 pounds (27 kilograms) of paper

- 1 bag or 94 pounds (43 kilograms) of Portland cement

- 15 shovelfuls or 65 pounds (29 kilograms) of sand

- Here is a by volume mix provided by Papercrete.com:[17]

- 12 parts paper

- 4-6 parts soft clay

- 2-3 parts lime putty

- This is the mix used in last year's Las Malvinas ecoladrillo schoolroom 2012

- 1 part cement

- 1 part prepared paper

- 1 part sand

Sawdust-Crete[edit | edit source]

Sawdust[edit | edit source]

Sawdust is considered a waste that is created during the manufacturing of coffins and many other products. It is a waste product that, if not added to the general waste stream is often burned. It often is not removed from the creation site, which allows it to become a hazard for fires and air quality.[18]

- BMP Association LTD is a company based out of Moscow that produces equipment for companies and experiments with different and new building materials, including sawdust concrete. They claim several benefits of using sawdust concrete:

- Fireproof

- Indoor humidity control

- Frost-proof

- Resistance to mold and fungi

- Compatibility with various other materials and finishes

- Much lower heat conduction than bricks: 0.08-0.17 Wt/m as opposed to 0.5-1.5 in brick.

- According to their website, this means that it takes half as much energy to heat a home with 20cm sawdust-crete walls than with 50cm brick walls.

- Much lower density: 400-850 kg/m3 as opposed to 1550-1950[19]

- Timbercrete is a company based out of Australia that specializes in bricks, pavers and finishes

Recipes[edit | edit source]

- From an article on Scribd.com:

- Sawdust is first mixed with minerals to resist decay, molding and rot. May somewhat mimic natural process of wood petrification.

- 85% wood

- 12% cement

- 3% fly ash

- The resulting product weighs half as much as ordinary concrete, can be pressed into blocks skin to Concrete Masonry Units and has an R-value of 18. Buildings using these blocks, known as "Faswall Forms" do not use mortar, they are instead stacked, rebar is placed between the spaces in the form and then the form is filled with concrete.[20]

- After World War II, a man named Friberg built his home in Idaho, USA with sawdust concrete. Mother Earth News did a follow-up article on his home thirty years later. The home was found to be in excellent condition, with little sign of deterioration and excellent insulation. This mixture was found to only have one quarter to one third the strength of ordinary concrete and Friberg recommended it for indoor use.

- By volume:

- 1 part cement

- 1 part diatomaceous earth

- 3 parts sawdust

- 3 parts shavings

- 1 part clay

- Clay, diatomite and cement were mixed first, then sawdust and shavings were added.

- This recipe was found on the Digest blog and is recommended for a durable concrete.

- 135 kg cement

- 135 kg slaked lime

- 600 kg sand

- 200 kg sawdust

- ~250 L water

- This site claims 80 days for hardening time[21]

- From an online book on building sauna floors:

- 2 parts sand

- 2 parts sawdust

- 1 part cement

- Cured for one month[22]

- This recipe is used for making bat caves:

- 4 Quarts wood chips

- 1 Quart cement

- Recommends only using CaCl in the water because sugars in the wood chips can keep the concrete from binding.[23]

- The NSW Good Wood Guide offers this recipe for a sawdust-crete. This site reccomends use as a non-load bearing infill.

- 3 parts sawdust - hardwood used for best results

- 2 parts sand

- 1 part cement

- Blend the dry ingredients, first sand and sawdust then concrete.

- Add water, only enough to hold, but not produce excess when the mixture is squeezed.[24]

Rice Hull-crete[edit | edit source]

In the community presentation with Las Malvinas rice hulls were mentioned as a potential resource for the community. A study done in India analyzed the possibility of using rice hulls in concrete blocks. In the study rice hulls were added at 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 percent as compared to the amount of concrete added to the mixture. Although workability of the concrete decreased, other factors such as tensile strength, impact strength, displacement and energy absorption were improved significantly. Also, the blocks with rice hulls added were found to tend to crack before failure as opposed to the plain concrete blocks, which would tend to fail without much warning.[25]

Rice Hulls[edit | edit source]

Rice hulls are the protective layer surrounding the rice grain that is composed of silica and lignin.[26] Composting, open burning and livestock feed are some of the common ways to reduce waste of materials from the food industry.[27] Rice hulls have been used in construction because of its potential low water absorption, thermal resistance and insulative properties. These properties resist expansion and absorption, which has allowed rice hulls to be used successfully as infill for houses..[28] Rice hulls have a water absorption of 123.7%.[29]

Recipes[edit | edit source]

One recipe for rice hull blocks from the book "Rice"

- 1 part cement by weight

- 0.25 parts rice hull by weight

- 0.35 parts water by weight[30]

- This translates from weight to volume to approximately:

- 6 parts rice

- 2 parts cement

- 1 part water

Rice Husk Ash-Crete[edit | edit source]

A study published in India's NBM Media site suggested the use of 10% by mass rice hull ash (RHA) to enhance various properties of cement. Resistance to acidic environments, compressive strength and surface moisture of cement blocks were all found to have increased with the addition of approximately 10% RHA. This also counts for use in mortar. Concrete blocks fared best with 12.5% RHA.[31] A Brazilian study concurred, finding that 10% RHA decreased total water absorption by up to 38%. Compressive strength increased, with mixtures both of 5% and 10% RHA (5% having a greater compressive strength). These blocks were aged up to 28 days.[32] The Center for Vocational Building Technology suggests using 30% rice hull ash in a cement mixture, and that the quality of performance is on par with 100% cement.[33]

Rice Husk Ash (RHA)[edit | edit source]

RHA is produced by the burning of rice husks and is a common by-product of rice production.[34] In Las Malvinas, there is a nearby producer of rice husk and also rice husk ash as a by-product of their activities. Rice husk ash is composed of 90-95% silicon dioxide and can improve the workability, stability, reduce cracking and reduce plastic shrinkage of cement.[35] It is also of interest for this project particularly for its ability to decrease the amount of cement needed.

Recipe[edit | edit source]

- 10% rice hull ash by mass added to cement or mortar.

- 12.5% by mass added for concrete.[36]

Mortar[edit | edit source]

Mortar can be made with cement, sand, and sawdust, although these mixes are known to be weaker than "traditional" mortars.[37] In a test of cement/sawdust mixtures, over 10% sawdust in a mortar decreased the compressive strength by more than half. Mixtures of 10% and less still had a significant effect upon the compressive strength of the mortar.[38] It is possible to utilize a lime-cement mortar, which consists of 1 part lime to 3 parts sand. Another option is to utilize compo-mortar which consists of 1 part cement, 1 part lime and 6 parts sand.[39]

Finishes[edit | edit source]

The finish used in the 2012 schoolroom project was composed of:

- 4 parts water

- 1/4 part lime

- 4 parts sawdust

- 3 parts sand

- 2 parts cement[40]

- In visiting the schoolroom this year, some of the walls were cracking, which could have been partially from the mixture for the finish, so this year's project will likely want to revise this mixture if it is the one chosen.

Roofing Materials[edit | edit source]

The roof of the Botica Popular will likely be of zinc sheets, similar to the 2012 schoolhouse project.

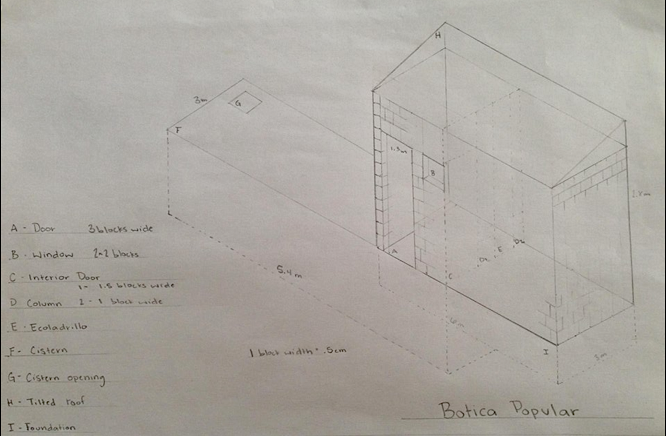

Sketch[edit | edit source]

This sketch was created to portray the dimensions and general layout of the Botica Popular. It includes the cistern, which the Botica Popular partially overlaps.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20180327013039/http://www.dominicanaonline.org:80/portal/espanol/cpo_clima.asp

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20180327013039/http://www.dominicanaonline.org:80/portal/espanol/cpo_clima.asp

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20180410163752/http://www.dominicanaonline.org:80/portal/espanol/cpo_clima1.asp

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20180410165113/http://www.dominicanaonline.org:80/portal/espanol/cpo_clima3.asp

- ↑ Sr. Vasquez, owner of block-making company

- ↑ Uhler, Frank G. "Mortar and cement compositions." U.S. Patent No. 2,437,842. 16 Mar. 1948. http://www.google.com.do/patents/US2437842

- ↑ Case, Gerald Otley. "Plaster and the like." U.S. Patent No. 2,016,986. 8 Oct. 1935. http://www.google.com.do/patents/US2016986?dq=making+lime+plaster

- ↑ http://www.traditionalandsustainable.com/TSB/Lime_Putty_files/Lime_Use_Guide-2.pdf

- ↑ http://www.traditionalandsustainable.com/TSB/Lime_Putty_files/Lime_Use_Guide-2.pdf

- ↑ Koski, John A. "How Concrete Block Are Made." Masonry Construction, October 1992, pp.374-377. http://www.madehow.com/Volume-3/Concrete-Block.html#ixzz2WDovZcR6

- ↑ interview with Jacob, 6/7/13, interviewed by: Holly Johnston, John Lococo, Elisabeth de Jong

- ↑ http://livinginpaper.com/

- ↑ https://www.appropedia.org/Las_Malvinas_ecoladrillo_schoolroom_2012#Papercrete

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20131021115648/http://masongreenstar.com/sites/default/files/Research_Report_Thermal_17p.pdf

- ↑ http://www.livinginpaper.com/tests.htm

- ↑ http://www.livinginpaper.com/mixes.htm

- ↑ http://www.papercrete.com/papercrete.html

- ↑ Davis, Gray, et al. "Feasibility Study on the Expanded Use of Agricultural and Forest Waste in Commercial Products."

- ↑ http://www.bmp.su

- ↑ http://www.scribd.com/doc/40318020/New-Chips-on-the-Block. 1/1/00. Ken Roseboro.

- ↑ http://digest-1.blogspot.com/2011/05/how-to-make-wall-with-good.html

- ↑ Sauna: a Complete Guide to the Construction, Use and Benefits of the Finnish Bath by Rob Roy. 2004. Chelsea Group Publishing

- ↑ http://cms.zwergfledermaus.de/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/BatCaves-recipe.pdf

- ↑ http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au/good_wood/sawment.htm. Sawdust sand and Cement. By Russell Andrews. The NSW Good Wood Guide

- ↑ Sivaraja, M., S. Kandasamy. Potential Reuse of Waste Rice husk as Fibre Components in Concrete. Vol 12. No 2. 211. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering. pp 205-217.

- ↑ Olivier, Paul A. "The rice hull house." The Last Straw 25 (2010). naturalhomes.org/img/ricehullhouse.pdf

- ↑ Davis, Gray, et al. "Feasibility Study on the Expanded Use of Agricultural and Forest Waste in Commercial Products."

- ↑ esrla.com/pdf/ricehullhouse.pdf

- ↑ Sivaraja, M., S. Kandasamy. Potential Reuse of Waste Rice husk as Fibre Components in Concrete. Vol 12. No 2. 211. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering. pp 205-217.

- ↑ Rice, Vol 2: Utilization. Editor:Bor S. Luh

- ↑ Mishra, Sudisht. Dr. SV Deodhar. Effect of Rice Husk Ash on Cement Mortar and Concrete NBM Media. October, 2010. http://web.archive.org/web/20160819035347/http://www.nbmcw.com:80/articles/concrete/18708-effect-of-rice-husk-ash-on-cement-mortar-and-concrete.html

- ↑ Tashima, Mauro M. Carlos A R Da Silva. Jorge L Akasaki. Michele Beniti Barbosa. The Possibility of Adding the Rice Husk Ash (RHA) to the Concrete. http://web.archive.org/web/20140308044155/http://congress.cimne.upc.es:80/rilem04/admin/Files/FilePaper/p282.pdf

- ↑ http://cvbt-web.org/?q=Rice-Husk-Ash-Cement

- ↑ Tashima, Mauro M. Carlos A R Da Silva. Jorge L Akasaki. Michele Beniti Barbosa. The Possibility of Adding the Rice Husk Ash (RHA) to the Concrete. http://web.archive.org/web/20140308044155/http://congress.cimne.upc.es:80/rilem04/admin/Files/FilePaper/p282.pdf

- ↑ Mishra, Sudisht. Dr. SV Deodhar. Effect of Rice Husk Ash on Cement Mortar and Concrete NBM Media. October, 2010. http://web.archive.org/web/20160819035347/http://www.nbmcw.com:80/articles/concrete/18708-effect-of-rice-husk-ash-on-cement-mortar-and-concrete.html

- ↑ Mishra, Sudisht. Dr. SV Deodhar. Effect of Rice Husk Ash on Cement Mortar and Concrete NBM Media. October, 2010. http://web.archive.org/web/20160819035347/http://www.nbmcw.com:80/articles/concrete/18708-effect-of-rice-husk-ash-on-cement-mortar-and-concrete.html

- ↑ Elpel, Thomas J. Living Homes, Integrated Design and Construction 5th ed. p 114. Google Books.

- ↑ Bdeir, Layla Muhsan Hasan. Study Some Mechanical Properties of Mortar with Sawdust as a Partially Replacement of Sand." Anbar Journal for Engineering Sciences. 3/4/12. http://www.iasj.net/iasj?func=fulltext&aId=41133

- ↑ http://www.fao.org/docrep/s1250e/s1250e09.htm

- ↑ https://www.appropedia.org/Las_Malvinas_ecoladrillo_schoolroom_2012