m (Taking category out of MECH370 notice, putting in directly as cat tag.) |

m (rewriting {{wp}} links, to make a local wikilink followed by {{wp sup}} (superscript link to Wikipedia)) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Many macroscopic materials processing operations involve elevating the {{ | Many macroscopic materials processing operations involve elevating the [[temperature]]{{wp sup|temperature}} of the workpiece by some method, working the material at this elevated temperature where it is more ductile so less energy is required to deform it, then cooling the work piece back down to (usually) room temperature. Examples of processes that follow this concept include: | ||

* Welding: Heating one piece of metal to its melting point and permanently attaching it to another piece of metal. | * Welding: Heating one piece of metal to its melting point and permanently attaching it to another piece of metal. | ||

* {{ | * [[Annealing]]{{wp sup|Annealing}}: A heat treatment process which produces a specific [[microstructure]]{{wp sup|microstructure}} by removing plastic deformations in the microstructure while increasing softness and ductility and decreases toughness of the specimen <ref name = "Callister"> Callister, William D. Materials Science and Engineering - An Introduction. s.l. : Wiley, 2007. </ref>. | ||

* Shrink Fitting: Heating one object to expand a hole into which another part is forced. The resulting combination is cooled and the second part remains in the host part. This practice is common for tight clearances or solid fixation between parts. | * Shrink Fitting: Heating one object to expand a hole into which another part is forced. The resulting combination is cooled and the second part remains in the host part. This practice is common for tight clearances or solid fixation between parts. | ||

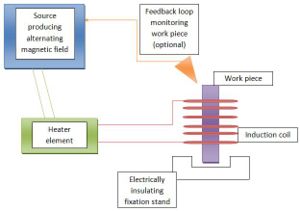

{{ | [[Induction heating]]{{wp sup|Induction heating}} (IH) uses an alternating magnetic field to induce a currents in the work piece, as predicted by [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faraday%27s_law_of_induction Faraday's] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenz%27s_law Lenz's] Laws. The induced current increases temperature due to [[joule heating]]{{wp sup|joule heating}} from the specimen's internal resistance, accomplished through multiple methods of heating, as discussed in this paper. [[Image:IH_apparatus_1.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig 1. Simplified schematic of apparatus. Feedback system is optional, but recommended to closely and accurately monitor the state of the workpiece. As discussed later, the alternating magnetic field can be established by either an AC or DC source.]] | ||

The temperatures reached in the electrically conductive specimen can be precisely controlled by several variables including: | The temperatures reached in the electrically conductive specimen can be precisely controlled by several variables including: | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

=== '''Heat Generation''' === | === '''Heat Generation''' === | ||

The combined work coil and work piece essentially compose a typical {{ | The combined work coil and work piece essentially compose a typical [[transformer]]{{wp sup|transformer}}. [[Eddy currents]]{{wp sup|Eddy currents}} are generated in the work piece (secondary coil) by the magnetic field from the work coil (primary coil), but since the work piece is electrically isolated (i.e. short-circuited) these currents are dissipated by joule heating, resulting in a rapid temperature increase. | ||

Typical in any electrical conductor, current is forced to flow through a thin layer at the surface of the part, creating the ‘skin effect’ which is responsible for some heat generated in the specimen <ref name = "Richie"> Richie's Tesla Coil Webpage. ''RF Induction Heating. ''[Online] [Cited: November 11, 2008.] http://www.richieburnett.co.uk/indheat.html </ref>. Since the pathway through which the current is permitted to flow is restricted (compared to being permitted to flow through the entire cross-section of the specimen), the resistance is greatly increased leading to greater joule heating and higher temperatures. | Typical in any electrical conductor, current is forced to flow through a thin layer at the surface of the part, creating the ‘skin effect’ which is responsible for some heat generated in the specimen <ref name = "Richie"> Richie's Tesla Coil Webpage. ''RF Induction Heating. ''[Online] [Cited: November 11, 2008.] http://www.richieburnett.co.uk/indheat.html </ref>. Since the pathway through which the current is permitted to flow is restricted (compared to being permitted to flow through the entire cross-section of the specimen), the resistance is greatly increased leading to greater joule heating and higher temperatures. | ||

For {{ | For [[ferrous]]{{wp sup|ferrous}} materials, the alternating eddy currents continuously magnetize and de-magnetize iron atoms in the crystal lattice. This constant switching generates relatively large quantities of heat due to the friction losses associated with these switching motions. Heating by this mechanism is called hysteresis heating as the energy lost (irreversibly) is due to loading and unloading of the magnetic properties of individual atoms. This process is present up to approximately 700ᵒC (the Currie temperature) in steels, beyond which steel looses its magnetic properties <ref name = "Richie"/>. A temperatures greater than the Currie temperature, only eddy currents and the skin effect are responsible for heat generation, thus the rate of temperature increase slows above the Currie temperature due to the elimination of one of the methods of heat generation. | ||

It is worth noting that while there are several similarities between an induction heating apparatus and a typical transformer, the distinct difference between the two is what gives each their function. Numerous steps are taken in transformer design to reduce the heat generated in the core(s) which represents lost electrical power or wasted energy. Compare this to an induction heater where the thermal energy is used for joule heating and any remaining voltage at the end of the circuit is essentially wasted energy (i.e. not dissipated as heat). Essentially, they are of similar construction but share totally different goals. | It is worth noting that while there are several similarities between an induction heating apparatus and a typical transformer, the distinct difference between the two is what gives each their function. Numerous steps are taken in transformer design to reduce the heat generated in the core(s) which represents lost electrical power or wasted energy. Compare this to an induction heater where the thermal energy is used for joule heating and any remaining voltage at the end of the circuit is essentially wasted energy (i.e. not dissipated as heat). Essentially, they are of similar construction but share totally different goals. | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

''This paper was originally planned to cover the process of induction annealing; using induction heating to raise the temperature of a specimen to its annealing temperature rather than using the current methods, which is commonly a gas-fired oven. The benefit of using induction heating is that higher heating rates can be achieved, and the process can be specifically targeted to a region of the work piece (i.e. annealing only one end of a metal bar, rather than the whole bar). A benefit of the ovens is that the entire specimen is treated at the same temperature at the same time, resulting in a uniform product, however more energy and time are required for the process. The following section briefly outlines the reasons to anneal an object using any method, and the mechanism used.'' | ''This paper was originally planned to cover the process of induction annealing; using induction heating to raise the temperature of a specimen to its annealing temperature rather than using the current methods, which is commonly a gas-fired oven. The benefit of using induction heating is that higher heating rates can be achieved, and the process can be specifically targeted to a region of the work piece (i.e. annealing only one end of a metal bar, rather than the whole bar). A benefit of the ovens is that the entire specimen is treated at the same temperature at the same time, resulting in a uniform product, however more energy and time are required for the process. The following section briefly outlines the reasons to anneal an object using any method, and the mechanism used.'' | ||

There are three steps involved in any {{ | There are three steps involved in any [[annealing]]{{wp sup|annealing}} process: | ||

* Heat up: increase temperature at a prescribed rate to the annealing temperature. | * Heat up: increase temperature at a prescribed rate to the annealing temperature. | ||

* Soak: Specimen is left at annealing temperature until desired microstructure is obtained. | * Soak: Specimen is left at annealing temperature until desired microstructure is obtained. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

The rates and duration of each step can be varied to produce vastly different structures and physical properties from the same material specimen. All variables (i.e. time, temperature, pressure, atmosphere, etc.) must be carefully controlled for the entire process to achieve the desired final product. Also, there is no single best combination of these variables; they must be optimized for each specific processing configuration. | The rates and duration of each step can be varied to produce vastly different structures and physical properties from the same material specimen. All variables (i.e. time, temperature, pressure, atmosphere, etc.) must be carefully controlled for the entire process to achieve the desired final product. Also, there is no single best combination of these variables; they must be optimized for each specific processing configuration. | ||

The elevated temperatures of the annealing process increase atomic mobility and relax the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crystallite crystal lattice]. This permits the {{ | The elevated temperatures of the annealing process increase atomic mobility and relax the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crystallite crystal lattice]. This permits the [[diffusion]]{{wp sup|diffusion}} of atoms and defects through the lattice increasing grain size which reduces toughness while increasing ductility and softness. The total number of defects is reduced, while those remaining are combined in their lowest energy configurations. The resulting microstructure is one that is easier to work on from a production or manufacturing perspective (i.e. easier to machine, stamp or roll due to less tool wear, lower energy requirements, etc.). | ||

= Increasing Efficiency = | = Increasing Efficiency = | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ Energy Consumption of AC and DC IH and {{ | |+ Energy Consumption of AC and DC IH and [[MIG Welding]]{{wp sup|MIG Welding}} | ||

! !! '''AC IH''' !! '''DC IH''' !! '''MIG Welding''' | ! !! '''AC IH''' !! '''DC IH''' !! '''MIG Welding''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 17:24, 10 April 2010

Introduction

Many macroscopic materials processing operations involve elevating the temperatureW of the workpiece by some method, working the material at this elevated temperature where it is more ductile so less energy is required to deform it, then cooling the work piece back down to (usually) room temperature. Examples of processes that follow this concept include:

- Welding: Heating one piece of metal to its melting point and permanently attaching it to another piece of metal.

- AnnealingW: A heat treatment process which produces a specific microstructureW by removing plastic deformations in the microstructure while increasing softness and ductility and decreases toughness of the specimen [1].

- Shrink Fitting: Heating one object to expand a hole into which another part is forced. The resulting combination is cooled and the second part remains in the host part. This practice is common for tight clearances or solid fixation between parts.

Induction heatingW (IH) uses an alternating magnetic field to induce a currents in the work piece, as predicted by Faraday's and Lenz's Laws. The induced current increases temperature due to joule heatingW from the specimen's internal resistance, accomplished through multiple methods of heating, as discussed in this paper.

The temperatures reached in the electrically conductive specimen can be precisely controlled by several variables including:

- Composition: Material composition determines physical properties of the specimen such as heat capacity, thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, density, etc.

- Geometry: Size of the work piece (length, width and height) as well as intricate cross-sections and wall thicknesses of hollow parts determine temperatures achieved.

- Induction Field: The frequency and strength of alternating field determines the current induced in the workpiece and thus the heat generated.

Some alternatives to induction heating currently available include: gas furnaces which are large and expensive to construct and operate efficiently, and are only suited to heat an entire specimen rather than a targeted region; microwave processing which is capable of deeper penetration levels, but lower temperatures and heating rates; laser hardeningwhich focuses thermal energy at a point (smaller target than induction heating) but is less efficient. Induction heating has the benefits of variable heating targets (size, shape, complexity, etc.), high heating rates and repeatable results.

Some excellent video clips showing IH in action can be found here. Figure 1 also shows a simplified schematic of the apparatus used. The apparatus is explained in detail over the next few sections.

Background Information

Induction Heating

There are three components to a typical induction heating apparatus:

- High-frequency AC source: Typical signal frequencies are often between 5-30kHz for thick materials or deep penetration, while 100-400kHz are used for thinner parts or shallow penetration (i.e. surface treatments; case hardening) [2].

- Work Coil: Also known as the induction coil, a magnetic field is generated in its center when AC current is passed through the conductive work coil.

- Work Piece: Placed in the center of the work coil, the work piece must be electrically conductive or else no heat will be generated.

When a high-frequency alternating current is passed through the working coil of the apparatus, a magnetic field is generated, flowing through the center of the working coil. This magnetic field in turn induces a current to flow through the electrically conductive work piece which is to be heated. The simplicity of this procedure contributes to its wide applicability, including: surface heat treatments; sterilization of medical and other equipment; hot forming; brazing; curing; shrink fitting.

Heat Generation

The combined work coil and work piece essentially compose a typical transformerW. Eddy currentsW are generated in the work piece (secondary coil) by the magnetic field from the work coil (primary coil), but since the work piece is electrically isolated (i.e. short-circuited) these currents are dissipated by joule heating, resulting in a rapid temperature increase.

Typical in any electrical conductor, current is forced to flow through a thin layer at the surface of the part, creating the ‘skin effect’ which is responsible for some heat generated in the specimen [3]. Since the pathway through which the current is permitted to flow is restricted (compared to being permitted to flow through the entire cross-section of the specimen), the resistance is greatly increased leading to greater joule heating and higher temperatures.

For ferrousW materials, the alternating eddy currents continuously magnetize and de-magnetize iron atoms in the crystal lattice. This constant switching generates relatively large quantities of heat due to the friction losses associated with these switching motions. Heating by this mechanism is called hysteresis heating as the energy lost (irreversibly) is due to loading and unloading of the magnetic properties of individual atoms. This process is present up to approximately 700ᵒC (the Currie temperature) in steels, beyond which steel looses its magnetic properties [3]. A temperatures greater than the Currie temperature, only eddy currents and the skin effect are responsible for heat generation, thus the rate of temperature increase slows above the Currie temperature due to the elimination of one of the methods of heat generation.

It is worth noting that while there are several similarities between an induction heating apparatus and a typical transformer, the distinct difference between the two is what gives each their function. Numerous steps are taken in transformer design to reduce the heat generated in the core(s) which represents lost electrical power or wasted energy. Compare this to an induction heater where the thermal energy is used for joule heating and any remaining voltage at the end of the circuit is essentially wasted energy (i.e. not dissipated as heat). Essentially, they are of similar construction but share totally different goals.

Susceptor Heating

One of the requirements for induction heating is that the specimen to be heated is electrically conductive, which excludes many materials such as polymers and ceramics. To combat this fact, a susceptor, or metallic object, may be added to this non-conductive object to permit this type of heating. For example, a polymer to be melted could be placed in a metallic container, and the temperature of the metallic container be raised to the melting point of the polymer. The container is heated by induction while heat is transferred to the polymer by conduction. Typical susceptor materials include graphite, molybdenum, silicon carbide, stainless steels, niobium, aluminum and virtually any other conductive materials. An appropriate susceptor material is selected for each application, and is decided as a function of cost, thermal requirements, reusability and other factors [2]. A key factor in susceptor selection is that the melting point of the susceptor materials is lower than the processing temperature of the work material to be heated inside it.

Electrical Components and Considerations

The electrical control and power-delivery systems involved in an induction heater can be rather complicated, due to the current carrying requirements of various components. An inductor-capacitor circuit (LC-circuit), or resonant circuit, is used to ensure a sinusoidal function of a specific frequency is connected to the work coil, improving the electrical efficiency of the inverter. This circuit may be connected in either of two ways to the inductor coil:

- Series Connection: Connecting the LC-circuit in series with the working coil produces the desired sinusoidal output signal at low currents. This means that many coils of the working coil are required to achieve a strong magnetic field and thus high induced currents and temperatures. The heating power builds due to the resonant characteristics of the circuit which increase voltage over time. This requires a close proximity between the inverter and working coil to keep losses in the remaining electrical components to a minimum. This circuit is shown in Figure 2a.

- Parallel Connection: Connecting the LC-circuit in parallel with the working coil also produces the desired sinusoidal output signal, but at higher currents for the same amount of losses (i.e. same electrical efficiency). In this configuration, shown in Figure 2b, the capacitor takes some of the current while leaving a large voltage drop over the inductor. This effectively reduces the current through the inductor while keeping the same inducting power. This also greatly reduces losses in the inductor, permitting the inductor and signal source to be farther away from each other.

-

Fig 2a: LC-circuit with inductor and capacitor connected in series. [3]

-

Fig 2b: LC-circuit with inductor and capacity connected in parallel. [3]

There are several other properties of the electrical system which must be optimized, and are done so based on laws which govern electrical systems. These include: impedance matching of components between inductor and the work coil to evoke the highest possible current in the work piece while maintaining a low current (and high voltage) in the inductor; built-in safety and back-flow current protection to protect other sensitive electrical equipment; methods of power control. All of these electrical production and control elements of the system are beyond the scope of this paper.

Annealing

This paper was originally planned to cover the process of induction annealing; using induction heating to raise the temperature of a specimen to its annealing temperature rather than using the current methods, which is commonly a gas-fired oven. The benefit of using induction heating is that higher heating rates can be achieved, and the process can be specifically targeted to a region of the work piece (i.e. annealing only one end of a metal bar, rather than the whole bar). A benefit of the ovens is that the entire specimen is treated at the same temperature at the same time, resulting in a uniform product, however more energy and time are required for the process. The following section briefly outlines the reasons to anneal an object using any method, and the mechanism used.

There are three steps involved in any annealingW process:

- Heat up: increase temperature at a prescribed rate to the annealing temperature.

- Soak: Specimen is left at annealing temperature until desired microstructure is obtained.

- Cool down: Usually back to room temperature.

The rates and duration of each step can be varied to produce vastly different structures and physical properties from the same material specimen. All variables (i.e. time, temperature, pressure, atmosphere, etc.) must be carefully controlled for the entire process to achieve the desired final product. Also, there is no single best combination of these variables; they must be optimized for each specific processing configuration.

The elevated temperatures of the annealing process increase atomic mobility and relax the crystal lattice. This permits the diffusionW of atoms and defects through the lattice increasing grain size which reduces toughness while increasing ductility and softness. The total number of defects is reduced, while those remaining are combined in their lowest energy configurations. The resulting microstructure is one that is easier to work on from a production or manufacturing perspective (i.e. easier to machine, stamp or roll due to less tool wear, lower energy requirements, etc.).

Increasing Efficiency

Impeder

Korean researchers conducted a three-dimensional computational analysis of high-frequency induction welding (HFIW) processes which included mapping of electromagnetic activities and the resulting eddy current distributions, joule heating, thermal conductivity and temperature distribution [5]. The analysis concluded that by including an impeder – a solid plug with low conductivity inserted into the hollow center of the shaft to be welded – eddy currents can be focused at the desired surface(s) of the work piece, increasing local temperatures. This means that less energy can be used to achieve the same temperatures or that higher temperatures can be achieved for the same energy costs.

A typical impeder material is ferrite, due to its low conductivity and relatively low cost and high availability. The lifespan of the impeder is another important concern; how many times can it be reused? If it contacts molten metal (reasonably likely in many of these high-temperature applications), the low conductivity can be ruined, the strength of the impeder is compromised in the direction of the molten metal resulting in a lower local eddy current density and temperature, defecting the work piece and warranting the discard of the impeder. To combat the melting of the impeder itself, it is usually liquid-cooled with the cold and hot streams of the cooling fluid leaving from the same end of the tube.

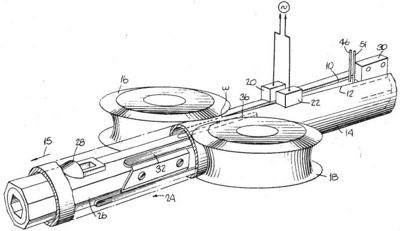

Figure 3 shows a typical impeder configuration. Note the rollers, which push the rolled surfaces of the pipe together to form the cylindrical shape while eddy currents are focused at the weld seam, or the faces which will meet along the weld line. The combination of temperature (due to joule heating of the focused eddy currents along these surfaces) and pressure (due to the rollers forcing the seam together), a weld is formed.

This research also yielded the following relationships between the various parameters and their effects on the work piece [5]:

- Both eddy current density and surface temperatures increased significantly with the inclusion of an impeder. Also, larger impeders had greater effects on eddy current density at the surface of the material, however if the impeder was too large and contacted molten metal it was to be discarded.

- Using a higher frequency AC source increased temperature, noted by a greater production of molten metal.

- Higher temperatures were reached for lower rates of motion of induction coil relative to work piece.

- Eddy current density and temperature were found to be maximized in thinner-walled tubes (i.e. smaller specimens) and peaked specifically at the point on the work piece coinciding with the center of the work coil.

Numerically, this research showed that by including an impeder in a HFIW apparatus, the maximum eddy currents generated are on the order of ten-times those generated without the impeder. Similarly, maximum temperatures reached were over twice those achieved without the impeder [5]. By focusing the eddy currents in the work piece at the locations of interest, less energy can be used to achieve the same temperature profile, or using the same energy higher temperatures can be reached.

Testing Apparatus

It is often desirable to test the effect of multiple inputs to an object which operates under complex conditions. For example, creep-fatigue testing is often used on turbine blades which operate at high temperatures and often under high mechanical loads due to pressure gradients, high angular velocities and hydrodynamic forces. An accurate, repeatable way to thermally affect the test specimen is through induction heating [6]. Low energy requirements, the avoidance of a complex conduction apparatus and an increase in heating efficiency of specific regions of the blade are several of the advantages inherent in induction heating which thermal testing capitalizes on. The unobtrusive apparatus is easily installed and leaves plenty of viewing room to observe the affect of heat and other forces on the specimen as they occur (as opposed to being tested in an insulated oven, for example).

Induction Heating with Semiconductors

As recently as 1990, semiconductors have revolutionized the induction heating industry [7]. Instead of the magnetic field alternating as in a typical induction heating system (caused by AC current flowing through inductor coil), the work piece is rotated in a static magnetic field developed when DC current passes through a semiconductor cooled to approximately 30 K [7]. Eddy currents are only generated in the work piece when the magnetic field varies relative to the orientation of the work piece; so the part must be rotated in the static field to induce currents. The advantages to this technology are smaller thermal gradients, greater penetration by eddy currents which translates to more consistent heating from surface to core, very reproducible thermal profiles and point temperatures from one work piece to the next, increased durability of the magnetic field source since it is not moving and is not exposed to high temperatures generated; all while reducing the adjustment required from one work piece to the next and using less energy. Some of the negatives associated with this technology is a lower maximum temperature, since it is limited by the rotational speed of the work piece; balancing of the rotating part must be completed for each work piece; more difficult to work on two (or more) rotating pieces for processes like welding or brazing.

In conclusion, using semiconductors for induction heating processes increases operational efficiency to ~80% (compared with ~50% for typical AC induction heating processes), but limits the flexibility of the operation. Also, savings at initial investment are sacrificed for lower operating costs over the lifespan of the equipment.

Potential Problems with Induction Heating

Thermal Stress or Thermal Shock

Researchers at the Innovative Nuclear Fuel Division of the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute discovered that heating and cooling rates as well as physical dimensions of a specimen contribute to the strength of the material against thermal loadings. As the rate of temperature increase increased, larger differences in temperature between the surface and bulk or core of the specimen were noted. In extreme cases (heating rates upwards of 442 K/min), cracks were observed to penetrate clear through a uranium dioxide (UO2) specimen due to the large thermal gradients established by high heating rates. Again, the skin effect is a significant contributor to the high local temperatures at the surface which establish these thermal gradients.

Oxide Layers

Metallic oxides and oxide layers which cover many specimens serve as an electrical (and magnetic) insulator at room temperatures. For many specimens, this means that currents are difficult to induce in the skin layer and induction heating takes a great amount of time and energy to initiate. To combat this, the specimen may be pre-heated through a mechanism known as ‘skull melting’ involving a direct connection between the oxide layer and a high temperature source. The high-frequency electric field is present externally from this apparatus, and assumes heating responsibilities once the temperature of the specimen is high enough that the oxide layer can be penetrated by the high-frequency magnetic field.

Heat Affected Zone

Often accompanying a welding procedure is analysis of the heat affected zone (HAZ), or region immediately surrounding that to which heat was added. A similar process occurs in induction heating. The potential issue associated with the HAZ is the uncertainty associated with the resulting microstructure. Because of the accuracy achievable with induction heating, a specific area can be targeted for heat addition for a brazing, welding, annealing or other such process requiring heat. The remaining microstructure (taken a sufficient distance from the region of direct heat addition) remains unchanged, but the region immediately around the zone of heat addition is slightly altered, and represents microstructural uncertainty. The factors affecting the size and effect of the HAZ include [6]:

- Rate of heat input and cooling (faster rates of heating and cooling decrease size of the HAZ)

- Maximum temperature reached in zone

- Metallurgical factors such as pre-existing dopants or alloying elements, grain size, plastic deformation of microstructure, etc.

- Physical properties including thermal conductivity and heat capacity of metal.

Since induction heating focuses the thermal energy over such a small volume of material for a relatively short period of time (usually on the order of seconds, but may be as long as a few minutes), the HAZ is small compared to other processes. This permits a specimen to achieve very different properties at different locations, with little-to-no affect between regions.

Energy Consumption of Induction Heating

Due to the wide array of potential applications of the technology and possible work piece materials and configurations, it is not possible to state that induction heating methods are a certain percentage more or less efficient than another process. However, samples were taken from specific applications of the technology to gauge the general advantages in energetic efficiency of induction heating. The following table shows typical power consumption and efficiency ratings for equipment for each technology.

| AC IH | DC IH | MIG Welding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Power (from terminal) | 5-400 kW | 200 W | 3.74 kW |

| Typical Efficiency | 50% | > 80% | Note 1 |

| Output Power (to workpiece) | 2.5-200 kW | Note 2 | 2.8-4.5 kW |

- Note 1 - Efficiency of MIG welding varies greatly between application and operators. Other variables determining efficiency include power conversion technology (in welder assembly), weld (feed) rate, work piece material, and more.

- Note 2 - Output power for DC IH apparatus is not only related to input power to semiconductor, but also the speed at which the workpiece is rotated since the established magnetic field is static. Current (and thus, rate of heat transfer) is governed by the input power to the magnet, and to the rotational speed of the workpiece.

For more specific information on power consumption as it relates to the size of the workpiece and the depth of heating desired, click here.

Applications of Technology

Because of the relatively simple apparatus required, few stipulations on properties the work piece must possess and nearly infinite range of operating temperatures and heating/cooling rates, the list of applications for this technology is very long. Several of these processes are listed:

- Annealing: Using induction heating to increase the specimen to the annealing temperature can be done quickly and efficiently.

- Shrink fitting: Using induction heating to soften one component and forcing the other into the hole provides a secure, tight fit between components.

- Thermal Sealing: Heating low-temperature glue on the back of a foil seal in the lid of a medicine bottle melts the glue, sealing the bottle.

- Sintering Ceramics: Placing a ceramic powder in a susceptor to be heated via induction is an efficient way to transform a green compact to a sintered specimen [8].

- Increase Specific Energy Delivery: Higher energy densities can be achieved using induction heating compared to gas-fired furnaces or conduction, improving yield in processes like silicon production [9].

- Zone Purification: In semiconductor industry, silicon is purified by moving section of molten metal through the bulk. This can be done by moving bulk through inductor coil.

The only real limitation as to whether or not a material can be heated via induction is its electrical conductivity. The more conductive the material, the more effective and efficient an IH process is. However, inclusion of a susceptor can increase the potential applications to even include non-metallic (i.e. low-conductivity) materials.

Contact details

Please visit some of my references, linked below, for more specific information on induction heating and its applications. During my research, I discovered companies may offer a consultation for your specific process (i.e. recommended configuration, coil designs, power requirements, etc.) to construct an IH process. Contact such organization for more information.

This article is a work-in-progress, and will be continually updated as I develop the topic and scope further. I plan on further researching the subject of the impeder used in high-frequency induction welding and its potential use in other applications. If you have any information on this subject, or can recommend any resources please leave a note on the discussion page of this article. Thank you and I hope this article is of great use to you and your process.

References

- ↑ Callister, William D. Materials Science and Engineering - An Introduction. s.l. : Wiley, 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ameritherm Induction Heating. Dr. Dahake's Notebook. [Online] Ameritherm. [Cited: November 11, 2008.] http://www.ameritherm.com/appnotes.php.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Richie's Tesla Coil Webpage. RF Induction Heating. [Online] [Cited: November 11, 2008.] http://www.richieburnett.co.uk/indheat.html

- ↑ Apparatus for use in High Frequency Welding - United States Patent 3,588,427 Oppenheimer, Edgar D.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 'Kim, Hyun-Jung.' Three Dimensional Analysis of High Frequency Induction Welding of Steel Pipes With Impeder. Daejeon, Korea : Department of Mechanical Engineering - Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 'Kalpakjian, Serope and Steven R. Schmid.' Manufacturing Engineering and Technology (Fifth Edition). Upper Saddle River : Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fishman, Dr. Oleg S. Solar Silicon Part I. Advanced Materials and Processing. 2008.

- ↑ High-temperature superconductor powers induction heating system (Process Technology - Brief Article). 7, s.l. : Advanced Materials & Processes, July 2008, Vol. 166.

- ↑ Pressureless Rapid Sintering of UO2 Assisted by High-frequency Induction Heating Process. Jae Ho Yang, et al. 10, Daejeon-si : Journal of American Ceramic Society, 2008, Vol. 91.

![Fig 2a: LC-circuit with inductor and capacitor connected in series. [3]](/w/images/thumb/7/77/IH_RLcircuit-series_1.jpg/120px-IH_RLcircuit-series_1.jpg)

![Fig 2b: LC-circuit with inductor and capacity connected in parallel. [3]](/w/images/thumb/3/3e/IH_RLcircuit-parallel_1.jpg/120px-IH_RLcircuit-parallel_1.jpg)