Arid and semi-arid regions are often typified by short, intense rainfall events which contribute to short-term flooding and erosion. When surface runoff is high, little contribution is made from rainfall into the basin aquifer, and high-intensity flows transport sediments in channels and runoff beds to surface water bodies. In these cases a check dam can be used as a rainwater catchment technique for aquifer recharge.

What is a check dam?

A check dam is a permeable barrier placed in the flow path of an ephemeral waterway such as a channel, stream, ditch, or spillway (these terms are used interchangeably throughout this page) to hinder flow and cause upstream pooling. This pooling of water increase infiltration of rainfall to groundwater and reduces effects of erosion while trapping transported sediments and preventing downstream transport. Check dams have been shown to be particularly effective in trapping sediments when placed in gullies in areas with severe land relief.[1]

Small-scale traditional check dams are typically made from natural rock, wood, or scrap concrete 10-24 inches in diameter. Temporary check dams can also be constructed from fabric, straw bales and brush. Other specific types of check dams include a gabion (traditional check dam with additional wire-wrapping to provide increased stability and silt fences commonly seen in roadside ditches and near construction sites). While they are ideal for ephemeral applications susceptible to flash flows in response to rainfall events, check dams have also been successfully implemented in urban stormwater settings, regions of severe topographic relief, and in flat lands as a means for diversion of runoff for other uses.

History

Some of the earliest known check dams are located in North Africa and are thought by archeologists to date back to Roman or Pre-Roman times[2]. These check dams were typically used to slow and divert water for local irrigation. Check dams have historically been used and continue to be used in applications that are responsive to rainfall events rather than perennial streams and rivers. They have been successfully implemented in arid and semi-arid regions such as the southwestern United States, Gujarat region in India, and drylands in northern Africa, as well as other regions. Implementation of check dams is increasing in urbanized settings to provide flow regulation in stormwater collection ponds due to cost and ease of construction and minimal required maintenance[3]

Engineering Theory

Check dams function by reducing the flow rate of water through a channel, causing accumulation of water immediately upstream. Flow rate in a waterway is a function of the velocity and cross sectional area of water in the waterway, and can be estimated as shown:[4]

Equation 1:

where

- Q = Flow Rate (m3/s)

- v = Average water velocity in channel (m/s)

- A = Cross-sectional area of water in channel (m2)

From Equation 1 it can be observed that given v remains constant, Q decreases as A is decreased. Rate of accumulation of water immediately upstream can determined from a simple mass balance:

Equation 2:

where

- Qin = Flow rate of water in spillway upstream of check dam (m3/s)

- Qout = Flow rate of water through the check dam (m3/s)

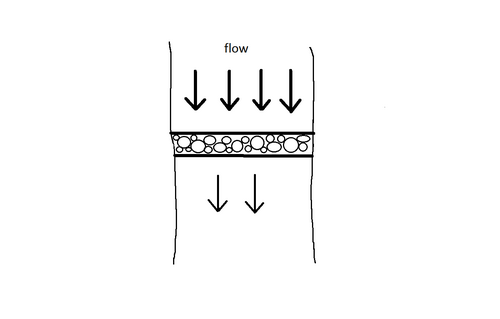

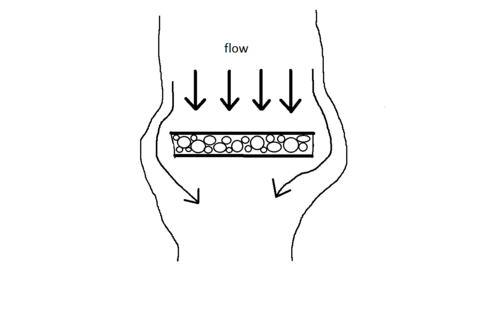

In order to determine Qout, the amount of cross-sectional area reduced by the check dam must first be determined. This value can be estimated by determining the porosity of the check dam. Porosity (n), is defined as the volume of air space (voids) in proportion to the total volume in a sample of soil of aggregate,[5] and since the ratio of volumes in a given sample is equal to the ratio of areas, porosity can be written as

or

Equation 3:

Avoids can be substituted for A in equation 1 to approximate Qout through a check dam. Porosity values for an angular aggregate such as that used for check dams range from 0.2-0.5, with a typical value of approximately 0.3 (24). These equations will provide a reasonable estimate only if the check dam is not submerged. In many instances it may be desirable to estimate the volume of water a check dam is capable of temporarily storing. This can calculated using equation 4:

Equation 4:

where

- V = Volume of water stored (m3)

- w = width of water stored upstream of check dam (m)

- h = depth of water column immediately upstream of check dam (m)

- l = length of water reservoir upstream of check dam (m)

While water level upstream the check dam will rarely remain constant due to Qout, Equation 4 provides a good estimation of the temporary storage potential provided by a specific check dam configuration. Given the depth of water immediately upstream of the check dam, infiltration can be estimated using Darcy's LawW for flow through a porous medium.[5]

Design

Placement of the check dam is the first consideration. The site should be in an upstream portion of the drainage or streambed where flow volumes are most manageable. Check dams should not be placed near bends or steep gradients in the waterway as this facilitates scouring and preferential flow of water around, rather than through, the check dam. Additionally, it may be advantageous to place the check dam in an area where there are abundant construction materials (i.e. appropriately-sized rocks), although this may not be possible in all instances.

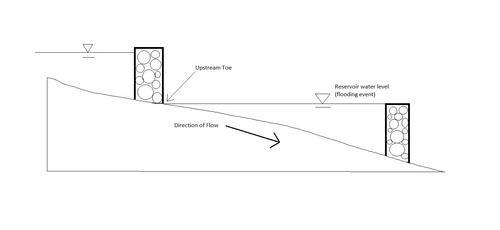

Check dams are ideally placed in series, starting in the upper reaches of the waterway and extending downstream. Spacing between check dams should be such that the height of the downstream check dam raises the water level in the spillway to the base of the check dam immediately upstream, as illustrated below. Check dams oriented in this fashion operate essentially as step-pools, and can be modeled as such[6]

Materials should be sourced prior to starting construction of the check dam. Check dam material, such as natural stones, concrete pieces, or hay bales, should be collected and transported to the site of the proposed check dam. If natural rocks or scrap concrete are intended to serve as the construction material, select rocks or concrete pieces at least 30 to 60 centimeters in diameter or at least 9 kilograms in weight.[7] Aggregate of this size is necessary to prevent washout of the check dam during high flow periods. Additionally, materials such as shovels and picks may be desirable for portions of construction and should be collected prior to building the check dam.

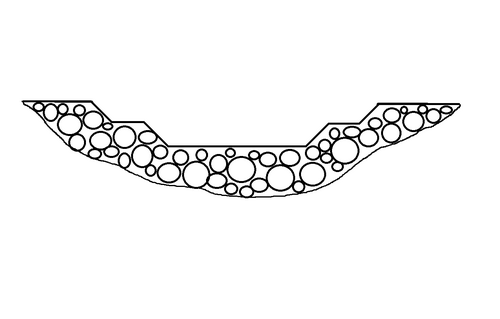

The check dam should be oriented perpendicular to the flow of the spillway, as shown in Figure 3. Start off during dry conditions by digging a trench across the waterway into both the waterway bed and the banks. Begin by digging a trench across the waterway and into the banks on each side. Proper setting is necessary in the embankment to provide stability of the check dam during high flows, particularly in the case of gabions. It is ideal to seat rocks on the bottom layer as to direct water flow at the bottom of the channel up and over, rather than under, the bottom layer of rocks.

Attention must be paid to height of the dam. Check dam construction should contain a low point at the center that is 1/2 the channel depth, and spans approximately 1/3 the channel width. This portion may be rectangular or or V-shaped, and is acts as the 'flow path' for water when the height of the reservoir becomes greater than the height of the check dam.

Portions of the check dam near the stream banks should be of slightly lower height than the embankment. If wire wrapping is not used, the check dam should have a height/Depth ratio of not greater than 1.5:1 to maintain stability during high flow events. Additional rock or other rip-rap may be placed at the toe of the check dam to provide scouring and moment resistance. When implementing check dams in series, begin with the uppermost check dam and construct new check dams by working gradually downstream.

Operation and Maintenance

A properly constructed check dam requires no operational input and minimal maintenance. Check dams should be inspected periodically after installation and after severe rainfall events. A check dam placed too low in a drainage or spillway without adequate upstream buffering (from additional check dams or otherwise) may be susceptible to scouring just downstream of the toe of the dam, and a check dam constructed without a proper flow path through the center of the dam may be susceptible to failure. Total scour may be estimated as the sum of degradation, contraction scour, and abutment scour;[8] a detailed discussion of scour is provided in Sturm. The photo to the right shows a check dam without a flow path through the center; the result of this was scouring around the outside edge of the dam. While the check dam will still pool water in during a rainfall event, it is no longer preventing sediment transport to lower portions of the watershed. In cases such as these, maintenance is required. Because the stability of the bank has been compromised, the check dam must be extended to cover the newly eroded area, and cross-sectional shape of the dam must be adjusted to facilitate flow of water through the center, rather than around, the dam.

Maintenance is also dependent on check dam material. Construction designs that utilize robust construction materials such as rock or concrete require less maintenance than check dams consisting of cloth, brush or hay bales. Robustness of design reduces necessity for check dam repairs after an intense rainfall event, and construction of a gabion may be desirable in waterways that endure high-intensity runoff volumes due to the structural integrity gained through wire-wrapping. After precipitation events or during spring flows, cloth check dams may have to be re-staked or replaced, and brush or hay bales must be repositioned as necessary to maintain effectiveness of the check dam.

Evaluation

Check dam performance can be analyzed based upon several criteria. One potential intended purpose of check dam implementation is increased rainfall contribution to groundwater. The effectiveness of a check dam can be determined by measuring infiltration from the temporary reservoir created by a check dam in response to a rainfall according to Darcy's Law[1]. Another purpose of check dam implementation is reduced sediment transport through a runoff channel. Sediment deposits can most easily be measured over time by recording sediment depth immediately upstream of a check dam during dry periods. An additional method to evaluate changes to sediment transport include comparison of downstream turbidity.

Additional evaluation of check dams can be made upon the basis of longevity of the dam and alteration of channel flow path. As described in the Construction section above, check dams must be constructed to withstand water flows typically responsive of a rainfall event. In addition, flow path of the channel should not be altered by the placement of a check dam. Scouring of the channel bank around the outer edges of the check dam is indicative of preferential flow path around, rather through the check dam. This can be remedied by lowering center height of the check dam, or altering construction materials used to increase passage of flow through the area of the dam perpendicular to stream flow.

Performance of check dams in real settings varies based upon construction design and execution. Robust check dams in large applications and small-scale check dams placed in ditches with low-intensity flow events have been documented to be in place for decades; the oldest known dam constructed without mortar is a gravity dam which is believed to have functioned for over 4,000 years.[9] Poorly constructed check dams can and have failed in the first high-intensity rainfall event to which they are exposed.

Impacts

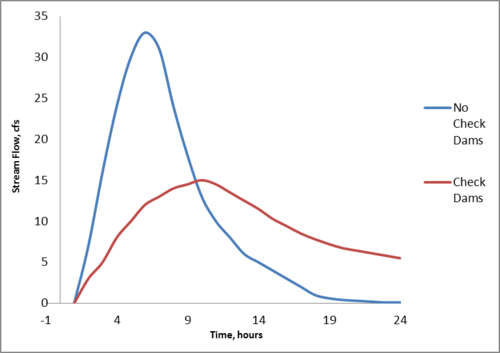

Check dams, when properly implemented, provide additional input to the local aquifer; a 1.5-2 m check dam can recharge an area of approximately 10 hectares[10]. Additionally they can as a temporary source of water to be diverted for irrigation as well as reduce erosion and sediment transport in runoff channels. Sediments that would have otherwise been carried down the waterway accumulate immediately upstream from the check dam, and can serve as suitable growing media for local plants capable of tolerating sporadic, intense exposure to water. A simple Hydrograph comparison can illustrate many of the positive impacts check dams provide.

As shown in Figure 4, a typical hydrologic pattern in rainfall-responsive waterways is a short, intense flow of water that quickly dissipates. This flash 'plug' of water is the contributor to erosion and flooding in a waterway. When implemented in series beginning in the upper stages of a watershed, check dams reduce the intensity of the hydrologic peak in a channel following a rainfall event by lengthening the amount of time water in which water is conveyed by the waterway. It is also notable that the time of concentration arrives later in a channel with check dams by adjusting stream gradient[11]; this provides additional flexibility in harvesting options if desired. As sediment accumulates behind a check dam it may become suitable for planting of local vegetation. In some areas, check dams may be used to support fruit trees and cereal crops.[12]

Check dam implementation may also contribute to several points of potential conflict. Check dams alter the flow characteristics of the waterway in which they are placed; although the impacts of check dams are largely positive (as discussed above), the moderated flow characteristics will affect downstream water users along the channel. Contingent upon water use, moderated precipitation response may be undesirable or problematic for downstream users. Check dam implementation affects not only hydrologic patterns, but water volume as well. The volume of water that check dams contribute to aquifer recharge is water that would otherwise have continued downstream. This may negatively impact downstream users with a high water-use application. These implications should be considered prior to construction with particular diligence given to regulatory requirements or guidelines that may dictate water use in the region. River basin management is greatly affected by environmental legislation; the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act of 1958 established that project purposes in a basin be coordinated with fish and wildlife conservation.[13] Additionally, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970[2], Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972[3], and Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1978 and 1978[4] provide additional guidelines and restrictions in the realm of basin management.

Dissemination

Distribution of construction methodology and and other information is currently underway through several organizations:

Permaculture Research Institute of America[14] The Permaculture Research Institute of America (PRI USA)[5] seeks to "work with communities worldwide, to expand the knowledge and practice of integrated sustainable agriculture using the whole-systems approach of Permaculture Design." The Institute acts as a resource and consults on projects spanning the globe.

The Permaculture Institute of Australia:[15] The Permaculture Institute of Australia (PRI Australia) [6] promotes the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems, including the use of check dams. Additional Permaculture Institutes include PRI Greece and PRI Turkey.

Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond Vols 1-3 by Brad Lancaster[7] This series of informational books discuss various rainwater catchment technology, with a specific discussion on check dams. These publications provide detailed discussion of project siting, construction methods and materials, and maintenance of check dams and other rainwater catchment techniques.

Sustainable Cities Institute The Sustainable Cities Institute[8][16] is a platform of sustainability resources and networking opportunities intended to be used as a tool to assist cities in sustainable development. The institute provides information on urban applications of check dams and bioswales in a stormwater management context.

Design Alternatives

A weir is an alternative to a check dam that utilizes impervious material such as cast-in-place concrete or steel. Weirs typically have square- or V-shaped notches that that direct flow through the center of the channel. Weirs are typically used in both ephemeral and perennial channels, and provide both a means to create a reservoir within a stream or river and an opportune location to measure stream flow. Check dams can also be utilized in this fashion. Transmittance of water through the cross-sectional area of the check dam can be estimated, and the check dam can be construction so that the shape of the flow path is known. Given this information, relatively accurate measures of stream flow can be gathered based upon depth of water flowing through the flow path of the check dam.[13] Another alternative to check dams is the placement of rip-rap over an extended length of the channel or stream. While rip-rap doesn't provide adequate protection against erosion of streambanks and may not provide the reservoir capacity of a check dam, use of rip-rap effectively dissipate kinetic energy in flowing water and reduce erosion in the center portion of the channel. Rip-rap may be more desirable than a check dam if high importance is placed on natural-looking aesthetics, such as a park or scenic waterway.

References

- ↑ Xiang-Zhou, Xu. "Development of check-dam systems in gullies on the Loess Plateau, China." Sediment Laboratory, Department of Hydraulics and Hydropower Engineering, Tsinghua University, 2004. Web.

- ↑ Lowdermilk, W.C. "Conquest of the Land Through Seven Thousand Years." U.S Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service. (1948): n. page. Web. 20 Apr. 2012. <http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010119lowdermilk.usda/cls.html>.

- ↑ Hari Krishna, Texas Manual on Rainwater Harvesting, Third edition, 2005. <http://web.archive.org/web/20151105183703/http://www.twdb.state.tx.us/publications/reports/RainwaterHarvestingManual_3rdedition.pdf>

- ↑ Sturm, Terry W. Open Channel Hydraulics. 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill International, 2010. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sterrett, Robert J. Groundwater and Wells. 3rd Ed. New Brighton: Johnson Screens, 2007. Print

- ↑ Castillo, C., R Perez, and J.A. Gomez. "A conceptual model of the hydraulics of check dams for gully control." Geophysical Research Abstracts. 14. (2012): n. page. Web. 25 Apr. 2012. <http://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2012/EGU2012-10719.pdf>.

- ↑ Lancaster, Brad. Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond. 1st Ed. Vol 2. Tucsan: Rainsource Press, 2008.

- ↑ Richardson, E.V, and S.R. Davis. Evaluating Scour at Bridges. Report No HEC-18. Washington, DC: FEeral Highway Administration, U.S Department of Transportation, 2001.

- ↑ Mares, Michael A. Encyclopedia of Deserts. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. Web.

- ↑ "Sardar Patel participatory water scheme." Water Resources. Narmada Water Resources, Supply Department, 12 Jun 2011. Web. 25 Apr 2012. <http://guj-nwrws.gujarat.gov.in/showpage.aspx?contentid=1538〈=English>.

- ↑ Roshani, Reza. Evaluating the effect of check dams on flood peaks to optimise the flood control measures. MA thesis. International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, 2003. Web. <http://www.itc.nl/library/Papers_2003/msc/wrem/roshani.pdf>.

- ↑ Thomas, David S.G. Arid Zone Geomorphology: Process, Form, and Change in Drylands. 3rd Ed. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Print.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Wurbs, Ralph A., and Wesley P. James. Water Resources Engineering. 1st Ed. Prentice Hall, 2001. Print.

- ↑ "Mission Statement." Permaculture Institute of America. N.p., 2008. Web. 25 Apr 2012.

- ↑ "About." Permaculture Institute of Australia. PRI Australia, 2012. Web. 25 Apr 2012.

- ↑ "Overview." Sustainable Cities Institute. The National League of Cities, 2012. Web. 25 Apr 2012. <http://www.sustainablecitiesinstitute.org/view/page.basic/overview>.

Bibliography

- Chin, David A. Water Quality Engineering in Natural Systems. 1st Ed. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2006. Print.

- Fetter, C.W. Applied Hydrogeology. Fourth Ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2001. Print.

- Jean-marc Mwenge Kahinda, Akpofure E. Taigbenu, Jean R. Boroto, Domestic rainwater harvesting to improve water supply in rural South Africa, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, Volume 32, Issues 15–18, 2007, Pages 1050-1057

- J.S. Pachpute, S.D. Tumbo, H. Sally, M.L. Mul, Sustainability of Rainwater harvesting Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa, Water Resources Management, Volume 23, Number 13, 2815-2839. 2009

- Mitsch, William J., and James G. Gosselink. Wetlands. Fourth Ed. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2007. Print.

- N. Ibramo, P. Munguambe, Rainwater Harvesting Technologies for Small Scale Rainfed Agriculture in Arid and Semi-arid Areas, Waternet, 2007

- P. Houston, D. Still, Rainwater Harvesting: a neglected rural supply option. Partners in Development.

- Rainwater harvesting: a lifeline for human well being. United National Environmental Programme

- Rainwater Harvesting Agriculture: An Integrated System for Water Management on Rainfed Land in China's Semiarid Areas. Fengrui Li, Seth Cook, Gordon T. Geballe, and William R. Burch Jr AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 2000 29 (8), 477-483

- Rainwater Harvesting and Utilization, United National Environment Programme newsletter, http://web.archive.org/web/20190819133315/http://www.unep.or.jp:80/ietc/Publications/Urban/UrbanEnv-2/9.asp

- Sibonginkosi Moyo, Takura Nyimo, Jo Smet, Kristof Bostoen, Rainwater Harvesting in Southern Africa: Regional Annex, Water, Engineering, and Development Centre 2006, Loughborough University

- Th.M. Boers, J. Ben-Asher, A review of rainwater harvesting, Agricultural Water Management, Volume 5, Issue 2, July 1982, Pages 145-158, ISSN 0378-3774, 10.1016/0378-3774(82)90003-8. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378377482900038)

- Th.M. Boers, Rainwater harvesting in arid and semi-arid zones, INternationa Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement, 1994

- Xiao-Yan Li, Jia-Dong Gong, Compacted microcatchments with local earth materials for rainwater harvesting in the semiarid region of China, Journal of Hydrology, Volume 257, Issues 1–4, 1 February 2002, Pages 134-144, ISSN 0022-1694, 10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00550-9. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022169401005509)

Contact

- Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond: http://www.harvestingrainwater.com/

- Permaculture Research Institute USA: http://www.permacultureusa.org/

- Permaculture Research Institute Australia: http://www.permaculture.org.au/

- Sustainable Cities Institute: http://www.sustainablecitiesinstitute.org/view/page.home/home