Introduction

Carbon fiber has been commercially produced since the 1960’s after it was developed in 1956 by Roger Bacon [1]. Carbon fiber composites are valued for their high Young's modulusW and tensile strength as well as their light weight. Some forms of carbon fiber are also good heat conductors so are valued in the electronics industry[2].

Underlying Principles

Carbon Fiber Precursors must undergo stabilization and carbonizationW to become finished carbon fiber.

Precursors

Polyacrylonitrile

Polyacrylonitrile(PAN) is a polymer chain created from the polymerizationW of acrylonitrileW monomers. The polymerization reaction is shown in figure 1. PAN is most often produced using the Sohio Method. PAN will degrade before its melting temperature and therefore cannot be melt spun, therefore a wet spin method is used, secondly due to the aforementioned properties of PAN, pure PAN is rarely used, it is often combined with another polymer.[3]

Mesophase Pitch

Mesophase pitch is traditionally created from petroleumW or coalW tar. It is made out of fused aromatic chains.[4] Mesophase pitch does not lose its properties as its temperature approaches melting point so it can be melt extruded and therefore the extrusion process does not need solvents used in wet extrusion process. The properties of Mesophase pitch can be controlled during extrusion which has implications on the final properties of the carbon fiber[5]

Stabilization

Precursors must be stabilized before they can be carbonized. The effect of stabilization is to crosslink the polymers. The purpose of cross linking the polymers is to prevent relaxation and chain scission during carbonization. For both processes the sample is exposed to an atmosphere of air at temperatures of 200-300ºC. In PAN chains stabilization causes both cyclization and dehydrogenation, the sample must also be kept under tension to prevent relaxation of the chains. Pitch samples do not need tension applied because they are already aligned. Stabilization in mesophase pitch fibers causes the formation of ester and anhydride compounds within the pitch or the loss of aromatic carbon content[6]

Carbonization

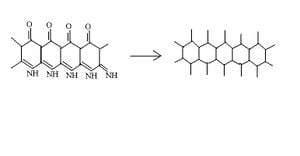

Carbonization is the process of converting organic material into carbon. The Carbonization process used to create carbon fiber is pyrolysis, which uses heat as a catalyst to increase the vibrational energy of atoms and break bonds between atoms in molecules. When used to form carbon fiber the pyrolysis breaks the bonds between carbon atoms and nitrogen atoms as well as the bonds between carbon atoms and oxygen atoms within the polymer. The carbon atoms then form bonds with other carbon atoms forming hexagonal chains, the nitrogen and oxygen components are removed as gas through the atmosphere which the carbonization is performed[7]

Process

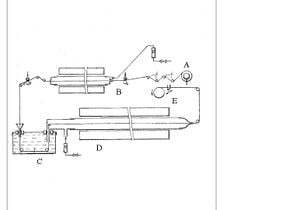

The process for producing Carbon fiber follows three to four steps: the extrusion of the precursor, the stabilization of the precursor, the carbonization of precursor, and optionally graphitization of carbon fiber. The extrusion of the precursor has a great effect on the final properties of the carbon fiber.[3] The stabilization of the precursor is a diffusion process and therefore depends upon the thickness of the carbon fiber it should usually last between 2 and 4 hours for PAN fibers with diameters of .001 to .0005 um [8] Carbonization has been shown to be optimized at temperatures between 1500ºC and 1600ºC.[7] Graphitization occurs at temperatures from 2500ºC to 3000ºC and is also conducted in an inert atmosphere. To optimize the amount of inert gas required to maintain the purging atmosphere of the carbonization and graphitization step without decreasing the opening port to a size where it may damage the fiber passing through it a liquid can be used to create a seal at the opening port. Potential liquids must not react with the precursor as it passes through them; liquids which may be used with PAN based fibers include benzene, heavy gasoline or mercury. This process is shown in figure 2.

. The inert agent creates a seal between the oxygen atmosphere which the polymer is oxidized in and the inert atmosphere of the carbonization. This allows the orifices which the fiber must pass through between the oxidation stage and carbonization stage to be large enough to avoid damaging the fibers while still maintaining a seal. The seal allows smaller amounts of inert gas to be used to maintain an oxygen free atmosphere.[9]

Improvements

As stated above the properties of the precursor will have a great effect upon the properties of the carbon fiber produced. To greatly improve the qualities of the carbon fiber produced a high quality specialized precursor can be used; however, high quality precursors are much more expensive. Therefore to improve the economics of producing carbon fiber a commercially produced precursor can be used.[10] When selecting a commercially produced precursor, the inclusion of itoconic acid monomer within the copolymer will facilitate stabilization by initiating cyclization.[11] Furthermore, selecting a precursor with a smaller diameter will reduce the time required for stabilization and increase the chance that stabilization is completed through the entire precursor. Control over the stabilization process can also contribute to the final properties of the carbon fiber. The heating profile can be varied to create greater diffusion of oxygen within the precursor to increase stability.[10] Experimentally it was found that a commercial PAN precursor wet spun containing 94% acrylonitrile, 4.7% methyl acrylate, and 1.3% itaconic acid with a cross section of 176.7 um squared when stabilized with a heating profile of 25ºC-200ºC in 60 minutes and held at 200ºC for an hour then heated to 210ºC in 30 minutes and held for an hour then heated to 220ºC and held for an hour then heated to 245ºC and held for an hour produces carbon fiber with a tensile strength of 2710 MPa. This carbon fiber was the optimal carbon fiber produced in this study.[10]

Economics

It was found that carbon fiber production costs can be divided into six categories:

- Material,

- Process Materials,

- Energy,

- Labor,

- Capital and

- Other.

Of these categories Material makes up for 44% of the overall cost, Process Materials is 6%, Energy cost is 15% of the overall cost, Capital makes up 21% of costs, Labor is responsible for 9% of costs and other costs make up 5% of the overall costs.[12].

Methods to improve the energy efficiency of this process should be considered. [expansion needed]

Carbon fiber fit for commercial applications can be produced for as little as $5.83 per pound. This is broken down into $1.90 for the precursor, $0.12 for pretreatment, $1.51 for stabilization and oxidization, $1.19 for Carbonization and $1.11 for sizing surfacing and quality control. This is the price per pound for producing carbon fiber out of a commodity acrylic fiber and does not include the overhead costs of building the tow or ovens used in each process. These costs are at their 2002 level and will be slightly lower due to advancements in technology.[13]

Applications

Carbon fibers have many applications due to their high tensile strength, young's modulus and low density. When woven into composites and combined with a resin, carbon fibers may be utilized to provide an extremely strong and lightweight material. Carbon fiber composites are used in many industries such as automotive (car bodies), recreation (rackets, golf clubs, pressurized paintball tanks), prosthetics (cheetah flex foot), and many more.

Potential Alternative: Carbonized Chicken Feathers

Carbonized chicken feathers (heated or "baked" in the absence of oxygen) appear to have some very interesting structural properties, similar to carbon nanotubes. However, carbon nanotubes are much more expensive and consume large amounts of energy during production (see above). This means that the market for them favors large-scale, capital-intensive modes of production. In contrast, chicken feathers are a byproduct of the poultry industry with disposal costs and currently little use. A publication in 2009 showed that carbonized chicken feathers can store large amounts of hydrogen and hence may be useful for hydrogen-powered vehicles (source). But the more interesting application may be the mechanical strength of these fibers. It may be possible to embed them in a thermoplastic resin and weave very thin strands of these composites into super-strong yet dirt-cheap fibers and fabrics. The abstract below has some details on the carbonization process.

Relevant Abstract found here: http://acs.confex.com/acs/green07/techprogram/P41563.HTM Friday, 29 June 2007 - 10:10 AM New York Room (Capital Hilton Hotel) 209 Carbon microtubes from chicken feathers by Melissa E. N. Miller, University of Delaware, Newark, DE and Richard P. Wool, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. In the United States alone, 5 billion pounds of poultry feathers are generated annually and must be properly disposed. This creates land-fill disposal and potential health problems. This research uses this waste as a valuable feedstock for new, high-performance, bio-based materials. Containing 47.83% carbon, chicken feathers are hollow and strong in nature due to the 91% keratin content. This study takes the use of chicken feathers one step further, by carbonizing them to create strong, inexpensive, hollow fibers. Current research shows that with the carbonization method of heating the chicken feathers at 225 °C for 26 hours, followed by 2 hours at 450 °C in a nitrogen environment, results in carbonized fibers which maintain their hollow structure. These fibers are added to a soybean oil-based resin to make biocomposites. We are seeing a 236% increase in the composite storage modulus at 35 °C, from 0.639 GPa with 0% fiber to 2.145 GPa with 3.45 wt% fiber. The extracted fiber modulus is on the order of 142 GPa, comparable to low/medium modulus carbon fiber. Density gradient experiments show a density in the range of 1.325–1.43 g/cm3. The aspect ratio is ~102. Wide-angle X-ray scattering shows an interplanar spacing (d002) of 4.4 Å in the raw chicken feathers, and a structural change showing 3.36 Å for carbonized chicken feathers, similar to 3.43 Å found in commercial carbon fiber. The potential applications range from use in the aerospace industry to airbags, catalysts, ligament repairs, batteries, hydrogen storage, and fuel cells. This project was supported by the National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, grant number 2005-35504-16137.

Relevant Links: Carbonized Chicken Feathers

- Characterization of carbonized chicken feathers

- Article on ScienceDaily about hydrogen storage in chicken feathers

- interesting electron microscopy image of carbonized chicken feathers

- (Audio) ScienceFriday: Hydrogen Storage in Chicken Feathers?

- Richard P. Wool lab at Univ. of Delaware

References

- ↑ Jason Gorss, 2007, "Bacon's Breakthrough," 2008(November, 11th) pp. 1.

- ↑ Jason Gorss, 2007, "Carbon Fibers Today," 2008(November 11th) pp. 1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 D. D. Edie, The effect of processing on the structure and properties of carbon fibers, Carbon, Volume 36, Issue 4, 1998, Pages 345-362, ISSN 0008-6223, DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6223(97)00185-1. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TWD-3TKTYN2-2/2/adf793c4834457cd3d20fe2e47fa660e)

- ↑ M. Minus, S. Kumar, February 2005, "The Processing, Properties, and Structure of Carbon Fibers," JOM, 57pp. 52-53-58.

- ↑ Seong-Ho Yoon, Yozo Korai, Isao Mochida, Isamu Kato, The flow properties of mesophase pitches derived from methylnaphthalene and naphthalene in the temperature range of their spinning, Carbon, Volume 32, Issue 2, 1994, Pages 273-280, ISSN 0008-6223, DOI: 10.1016/0008-6223(94)90190-2. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TWD-48CXN3G-164/2/36525da5e9fceb8030cca25180edc1b3)

- ↑ J. Drbohlav, W. T. K. Stevenson, The oxidative stabilization and carbonization of a synthetic mesophase pitch, part I: The oxidative stabilization process, Carbon, Volume 33, Issue 5, 1995, Pages 693-711, ISSN 0008-6223, DOI: 10.1016/0008-6223(95)00011-2. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TWD-3YKM3S3-62/2/60a90d4fa394ce99964e67940f9f2686)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fitzer, E. and Frohs, W., The influence of carbonization and post treatment conditions on the properties of PAN based carbon fibers. In Carbon ‘88, Proceedings of the International Carbon Conference, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K., pp. 2988300, 18-23 September 1988.

- ↑ HIRATA MASUMI [JP], SAKURAI HIROSHI [JP], SAWAKI TORU [JP], "PROCESS AND COMPOSITION FOR THE PRODUCTION OF CARBON FIBER AND MATS," EP20030753946 20030925(EP1550747 (A1))

- ↑ [1] Roland Weisbeck, (3775535) .

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Arman Sedghi, Reza Eslami Farsani, Ali Shokuhfar, The effect of commercial polyacrylonitrile fibers characterizations on the produced carbon fibers properties, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, Volume 198, Issues 1-3, 3 March 2008, Pages 60-67, ISSN 0924-0136, DOI: 10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.06.052. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TGJ-4P2J036-3/2/452c536e69e7b9c464b1c8a12f31717f)

- ↑ Bahl and Manocha, 1987 O.P. Bahl and L.M. Manocha, Development of high performance carbon fibers from PAN fibers, Chem. Age India 38 (5) (1987), pp. 181–188.

- ↑ Cohn, S. M. and S. Das (1999). “A Cost Assessment of PAN Carbon Fiber Production Technologies: Conventional and Microwave Cases, draft paper, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, Feb

- ↑ Warren D. Low Cost Carbon Fiber Production, Transportation for the 21st Century, U.S. Department of Energy Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Program Oak Ridge National Laboratory. November 2002, Retrieved November 2008, http://www.ntrc.gov/pdfs/transportation2002/LowCostCarbonFiberProduction.pdf