Overview

A Bycatch Reduction Device is considered to be any mechanism which is added to fishing gear with the intention of providing escapement to unwanted organisms without harm to their health[1] . Further, bycatch, can be defined as the “extra or incidental catch, unobserved mortality, and waste” associated with the utilization of various fishing techniques both recreational and commercial.[2] With such an encompassing definition, the term ”bycatch” becomes inclusive of not only finfish, but marine mammals, reptiles, crustaceans, and even shellfish.

With its potential for conservation and fisheries management implications, the idea of reducing bycatch came to the forefront of fisheries management in the mid-1990s.[3] Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) however, were first introduced and requisite in the United States as of 1990.[4] The primary difference separating TEDs and BRDs comes down to the mechanics of how each device works. A Turtle Excluder Device creates a barrier through which large organisms such as turtles cannot pass and are deflected. Bycatch Reduction Devices on the other hand provide an outlet for fishes by relying on certain behavioral characteristics of the species targeted by the device.[5]

Following much research, the first legislation to take action towards managing bycatch in fisheries in the United States of America came about in 1996 through National Standard 9. National Standard 9 was an amendment to the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act and set up programs for the implementation of Bycatch Reduction Devices.[6] In the United States, Federal regulation of BRDs progressed further through a Congressional push to incorporate aspects of their use into the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Conservation Act.[7] Internationally, the European Union implemented regulations requiring the use of selective trawl methods in 2003 for their shrimp fisheries.[8] As a result of this large governmental push for the use of BRDs, various designs were incorporated into fishing gear across the United States and Europe. Up until today, there have been thousands of designs with no one design proving to be superior. These current designs of BRDs have expanded from the original intent of excluding turtles from trawl nets to now making efforts to reduce incidental shark catch in long-line fisheries, terrapins caught in Blue Crab pots, sea snakes in trawling operations in tropical waters, and even juvenile fishes and crustaceans in trawls worldwide. Current management of the Bycatch Reduction Device legislation in the United States falls to the regional fisheries offices managed by the National Aeronautic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). Internationally, the effort is being monitored by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and promoted through NOAA.

While there has been much progress recently, in implementing BRDs in large commercial fisheries, this is only half of the battle. The other half is introducing these ideas to artisanal fisheries, which make up roughly 90% of the workforce in the fishing industry on a global scale.[9] Without bycatch reduction in this large sector of the global fisheries the impacts of our fishing techniques may become exponentially greater. Further, research shows that while BRDs and TEDs are commonly sought for inclusion in marine and estuarine fisheries, their use in freshwater fisheries should not be undermined.[10] In fact, one turtle excluder device utilized in catfish trapping in Missouri reduced turtle bycatch by 84%;[11] a statistic which cannot be overlooked when seeking to expand the sphere of influence for bycatch reduction devices worldwide.

Design and Construction of a Selection of BRDs

When looking at Bycatch Reduction Devices and how they are designed, there are a few major aspects which should be kept in mind. Firstly, one should take into consideration that between 25% and 64% of global bycatch could be reduced as a result of the implementation of reduction technologies.[12] Secondly, it should be considered when developing or implementing a Bycatch Reduction Device that such technology is not without its governing principles. In this particular instance, Tauti’s Law provides such guidance. Tauti’s Law is a series of complex mathematical equations which serve to explain the change and underwater shape of fishing gear.[13] While it is not always a totally accurate representation of the final product’s use in commercial fishing settings, it can provide useful insight into the functionality of gear and how water and flow may exploit particular weaknesses in the equipment. Finally, one final aspect of BRDs to consider before implementing or developing your own technology is that there are two primary types of BRD. These can be grouped into those which utilize specific behavioral characteristics of the species to be removed and those which utilize deflection via a barrier such as a Turtle Excluder Device.[14] Below is an outline of various methods and technologies for reducing bycatch utilizing varying amounts of resources and technologies.

Change of Fishing Tactics and Seasonal Closures

The utilization of changing fishing tactics and/or the implementation of seasonal fisheries closures is perhaps the least technological of the bycatch reduction techniques but also one of the more effective. In changing fishing techniques from drift gillnets to fixed gillnets, the number of small cetaceans and seabirds which are captured can be greatly reduced.[15] Other ideas in the change of fishing tactics include a change in netting material from traditional monofilament to a more visible netting was able to reduce the capture of marine turtles without significant loss in capture efficiency.[16] The utilization of seasonal closures within a fishery also stands to provide bycatch relief in many fisheries. Along the Gulf Coast of the United States, closure of specific fisheries during sea turtle spawning seasons could potentially reduce the number of stranding’s and mortalities of the Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle by 39%.[17] Similar closures in other parts of the world where marine turtles are also present could serve as a cost efficient mechanism for reducing bycatch without the implementation of new technologies.

Escape and Deflection Mechanisms

Exclusion of Juvenile Finfish

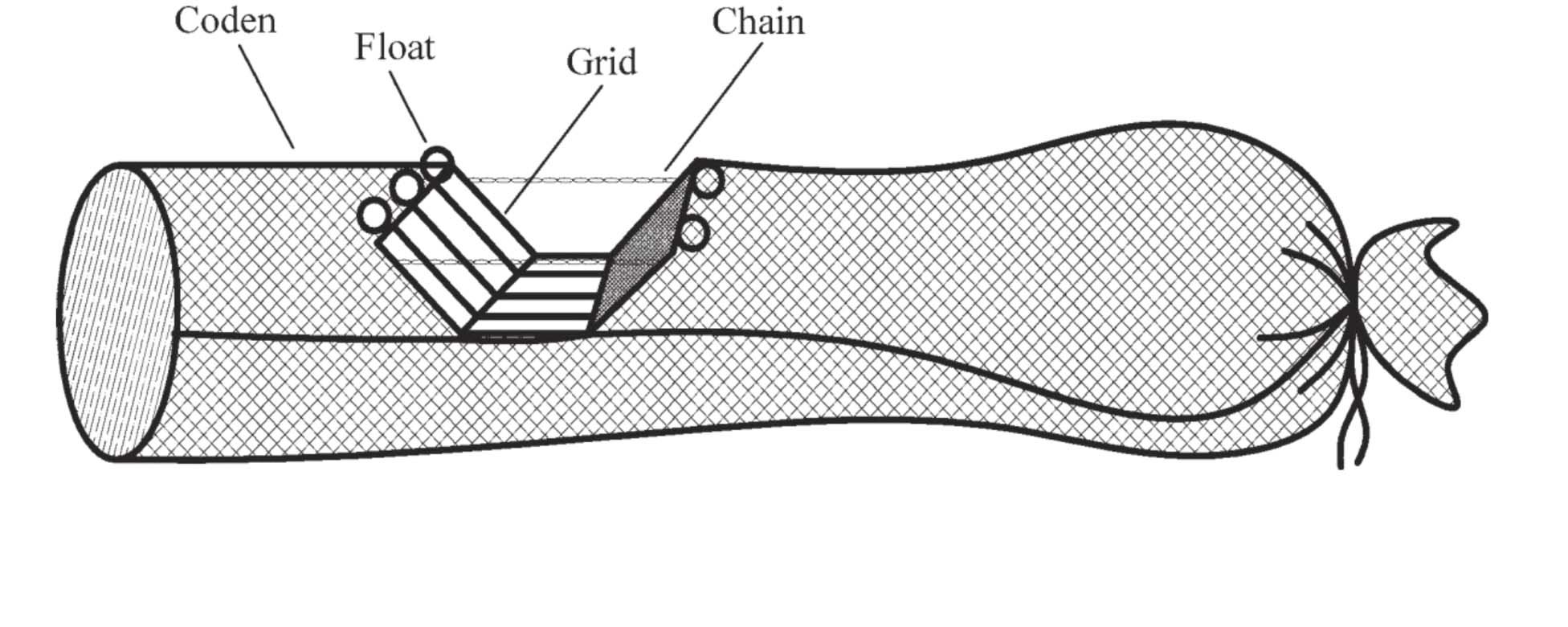

The implementation of a juvenile finfish excluder or Sort-X grid stands to be useful in the overall advancement of fishery health as it reduces mortality among the younger stage classes and ultimately leads to increased recruitment in many finfish species. One particular example of a juvenile exclusion device incorporates the use of three rectangular panels with hinges. Two of the three panels are angled off of a flat panel on the bottom to prevent entanglement in the net during escape (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Juvenile Excluder Device utilized in a Vietnamese trawl net fishery.[18]

Such a juvenile excluder device has been utilized in a Vietnamese fishery where, despite a reduction in overall bycatch, the fishers suffered a 9% loss in revenue.[19] Construction as described by Eayrs et al. 2007 can be achieved by connecting the following pieces with marine grade hinges. Panels are attached in a left to right manner so as to ensure the mesh panel is nearest to the end of the net. Panel 1 (overall dimensions of 0.5m X 0.2m) should be constructed of a frame of 8mm in diameter steel rods with 6mm diameter running parallel on the inside at a spacing of 20cm. The second panel (overall dimensions of 0.5m X 0.4m) should be constructed in the same manner as Panel 1. Finally, panel 3 should be 0.5m X 0.2m, have an outer frame made of 8mm diameter steel rods containing a section of mesh. The overall unit weighs in around 5Kg and should be accompanied by a set of floats to assist the device from sinking. The addition of chain connecting Panels 1 and 3 along the top as pictured in Figure 1 is also recommended.

Methods for Reduction of Crustacean Bycatch.

The reduction of crustacean bycatch can be a tricky measure. Due to the awkward size of some crustaceans, allowing for their escapement can also lead to some loss of target species. Literature analyzed for the construction of this page outlines three major types of crustacean reducing techniques. The first of these involves the utilization of varying mesh size and shape during net construction near the codend. Recommended mesh includes both square and diamond shapes in sizes of 56mm and 70mm.[20] Trials of the 56mm mesh in both shapes reported no significant losses in the literature, however the use of 70mm mesh in diamond shape, while sufficiently excluding crustaceans from the bycatch, resulted in significant losses of the target species[21] and therefore should be implemented only after careful consideration and investigation of the mesh size versus size of intended catch.

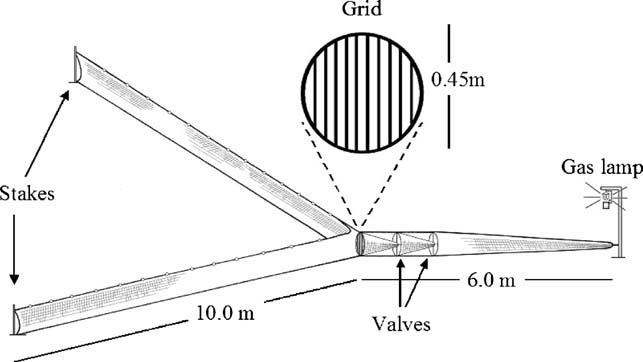

A second method for reducing the unwanted catching of crustaceans in bottom trawls involves the construction of a blocking grid across the mouth of the net. This low cost grid should be constructed of a wire hoop 5m in diameter and gridded with steel bars. Interstitial space should be equivalent to 25mm for optimum reduction while still maintaining effective capture of the target species.[22] Once finished, the grid should be placed at the mouth of the net, behind the wings as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Depiction of the proper placement of a crustacean reducing grid. Image from Vianna and D’Incao 2006.

A final method for increased reduction in crustaceans as bycatch is the utilization of the popular Nordmore grid. Construction of this device involves a grid of steel bars, 8mm in diameter, placed so that there is 35mm of space between each. This grid is then placed in the net anterior to the codend by a distance of 2m.[23] Additional recommendations for this device include a mesh size of 56mm with a diamond pattern (as a measure of secondary sorting) and the implementation of a mesh funnel to force the catch across the grate.[24] Further benefits of this device can also be found in areas of high Spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) abundance. Here a modification of this device, so that it is inserted into the net at either a 35° or 45° angle can assist in the reduction of Spiny dogfish capture.[25]

Finfish Funnels

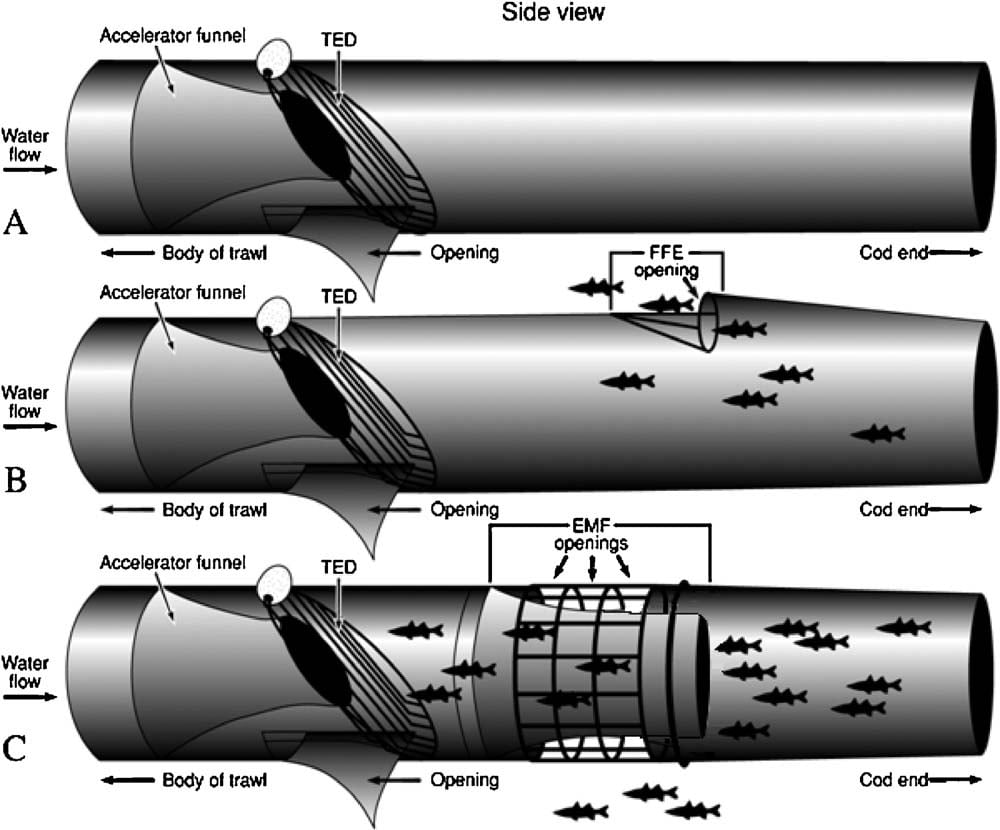

Aside from the aforementioned juvenile excluder device, other methods exist for the removal or reduction of finfish in bycatch. Specifically designed for bottom roller frame shrimp trawls, the Florida FishEye and Extended Mesh Funnel are particularly effective in reduction of finfish bycatch.

The Florida FishEye (FFE) device can be described as a small mesh and steel funnel placed in the top of the net which allows for the escape of small to medium-small finfish.[26] Construction of the FFE involves the construction of a half cone from a steel ring of 15cm in diameter. To supplement this ring, a 30cm long stainless steel pipe (13mm diameter) should be added on each side of the ring so as to form a conical shape as seen in Figure 3, diagram B. This is then installed near the codend of the net with the escape facing towards the mouth of the net.[27] Water moving across the net as the trawl is towed forces the cone down and creates an opening in the net for fish to escape. Due to behavioral characteristics of shrimp, they are less likely to swim while trapped in a trawl and therefore loss of target species is minimal from this device.[28]

Extended Mesh Funnels (EMF) are nylon webbing funnels constructed of 3.5cm stretch-mesh (Figure 3, diagram C). This funnel is surrounded by an escape portal of 21cm stretch-mesh about 1.5m in length and supported by a 2m diameter steel hoop which supports the netting and creates the opening for fish to escape.[29] Similar to the Florida FishEye design, this net allows for the escape of finfish and the retention of shrimp as a result of the shrimp’s inability to escape capture in a roller-trawl.

Figure 3. Diagrammatic representation of the Florida FishEye (B) and Extended Mesh Funnel (C) designs. Image from Crawford et al. 2011.

Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs)

Since the topic of Turtle Excluder Devices is so vastly encumbering, the below section will highlight only a few designs utilized in freshwater and estuarine systems for the reduction of terrapin bycatch. The proliferation of literature surrounding the marine counterparts of these devices, which are crucial in the conservation of marine turtles and indirectly other megafauna such as sharks[30] when designed so that the interstitial space is no greater than 10.3cm;[31] warrants an entire page devoted specifically to their history, design, and use. Their mention on this page is strictly limited to implementation in freshwater systems as a method of promotion of the idea as well as providing a historical background for the implementation of the idea of bycatch reduction devices.

Freshwater and Estuarine Turtle Excluders

Freshwater and Estuarine turtle excluders generally come in two forms; a preventative form and a survival form. The preventative form utilizes a funnel to prevent the entrance of turtles and terrapins into crab pots, fish traps, and eel traps, whereas the survival form is a modification of the trap so that entrapped turtles are able to survive until the pot is checked.

The development of a turtle excluding funnel has primarily been utilized in the eel fishing industry to keep the Diamondback terrapin out of pots.[32] Many designs to successfully accomplish this task have been made using PVC. The most common design features a 7.7cm ring of PVC which is attached to the inner ring of the funnel on eel pots. The use of PVC as the excluder makes the life of the device extremely long and the cost roughly $0.05 per pot.[33] Similar designs feature the use of a 4.5in by 12in wire funnel constructed of 11-gauge steel wire and cost roughly $1 per pot for implementation.[34]

Another popular design for the escapement and survival of trapped turtles and terrapins is the addition of a chimney. Chimney’s added to fishing pots for crabs are constructed out of poultry wire and extend an average of 120cm from the top of the pot, so as to be above the water level at all times.[35] Chimney’s with a closed top can be utilized for allowing the turtles to breathe while the removal of the top can provide a potential for escape.[36] Additionally, the addition of a chimney to the end of a fyke net for fish capture can be utilized as an escape route for captured turtles.[37] Construction of the chimney for a fyke net would be identical to the construction for a crab or eel pot with the exception of attachment and length which would be adapted for the individual situation.

Behavior Based Exclusion Devices

The Use of Visual Illusion

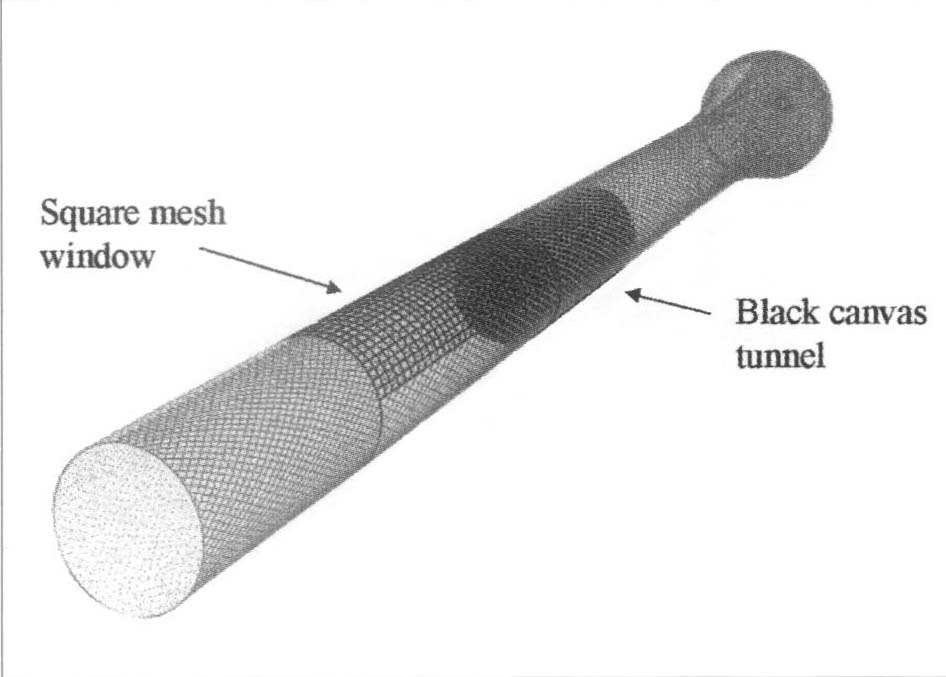

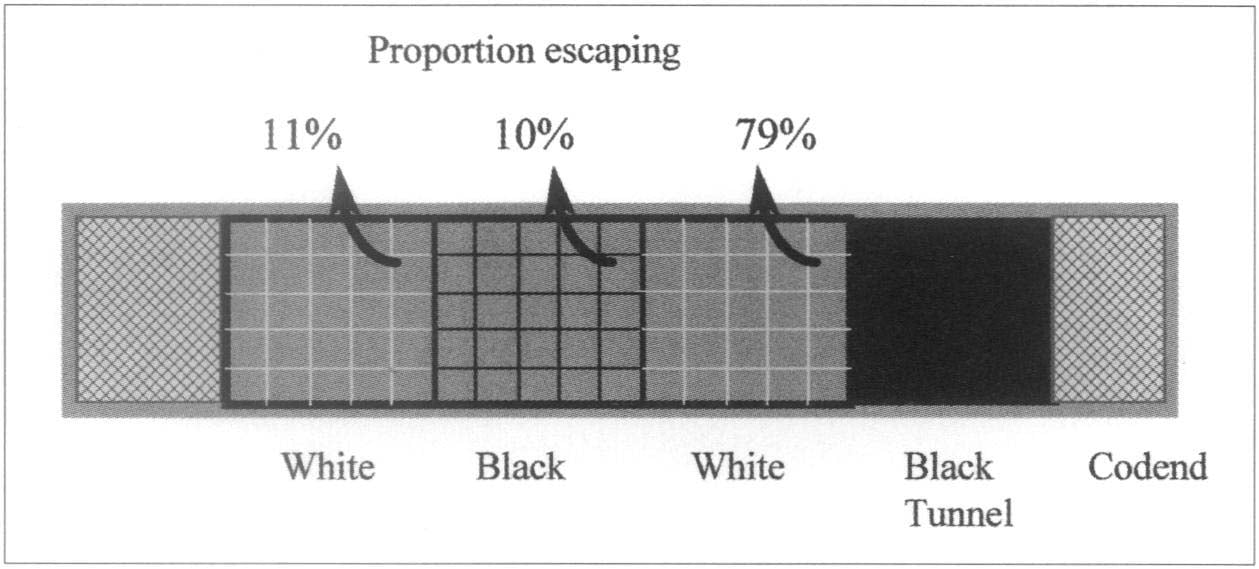

In addition to the previously mentioned methods for excluding bycatch by utilizing some sort of barrier or deflecting device, bycatch can also be minimized through the use of behavioral characteristics of a species. One of the most common uses of this method is the use of a visual illusion such as a section of the net being covered in black or white canvas. Having a section of canvas in the net creates a contrasting image in the eye of the fish, which scares them and causes them to seek an escape.[38] When constructing such an illusion (Figure 4), literature suggests that a band of canvas (black works best) 2m in length is attached to the net in an area surrounded by moderate diameter mesh to facilitate escape.[39]

Figure 4. Depiction of the canvas section in a trawl net for use as a visual illusion. Diagram taken from Glass, 2000.

Another method for reducing bycatch via behavioral traits of fish is the utilization of a separator trawl. Separator trawl nets (Figure 5) combine the utilization of varying mesh size in net construction with the implementation of visual illusions and a central plane separating the net into two main compartments.[40] When the fish become frightened during the canvas portion of the net, they tend to separate out by size into the upper and lower chambers of the net where a corresponding mesh size either permits escape or entraps them.

Figure 5. Diagram showing the alternation of mesh size, use of a tunnel, and percent of unwanted catch escaping with the use of a separator trawl. Figure taken from Glass, 2000.

There are various other mechanisms for excluding species based on the utilization of behavior; however these tend to be very species specific. The aforementioned designs are for more general use of eliminating smaller finfish and other applications of these designs should be researched further before being implemented in a fishing operation.

Operation and Maintenance

The operation and maintenance of bycatch reduction devices, especially those outlined in the previous section are very basic. Most all designs have been engineered in such a fashion so as to not interfere with the commercial fishing operation for which they were designed. General warnings on the operation of many of these designs would include the consideration of added weight to the net with the addition of a barrier or sorting grid as well as the potential for reduced speed of trawl from variations in the way in which water flows through and across the net as it is being towed. For fyke net and trap modifications to reduce inadvertent mortality and bycatch, the modifications outlined above do not replace the necessity of checking traps on a daily basis. Even the chimney designs which allow turtles and terrapins an opportunity to breathe are not designed for long periods of entrapment. Maintenance for all previously mentioned designs and for many of the other designs available in bycatch reduction technology involves basic repairs of grates, grids, and netting as well as careful cleaning after each use to increase longevity of life.

Evaluation of Effectiveness

All of the aforementioned reduction mechanisms have been tested in a scientific setting for effectiveness. During testing, care was taken to imitate commercial fishing operations when implementation or data from use in commercial operations was not available. However, due to the relaxation of many stringent experimental protocols, data from commercial fishing operations may not be as accurate as that obtained from laboratory testing.[41] To further test any of the aforementioned devices or other designs of bycatch reduction devices, there is no more valuable substitute than an experimental implementation into the commercial or recreational fishing industry. While this may not provide the most wholly scientific data, it does provide an accurate representation of how the device will work in real life applications and can assist in the assessment of potential profit loss or gain.

Impacts of Using BRDs

The impacts of utilizing bycatch reduction devices can be varied from operation to operation. How the device is constructed, how it operates in the water and even the definition of an impact can all be an influence. Research has indicated that in many instances the impacts of using BRDs are minimal on target species loss, especially in Australia where fisheye use has shown no major loss in the tiger prawn industry[42] and Europe where the implementation of gear restriction regulations caused no significant losses in the European Brown Shrimp fishery.[43] Further indication in the research on bycatch reduction devices indicates that there is a positive impact on the affected bycatch species. Use of BRDs has proven beneficial in the reduction of elasmobranch bycatch through the use of the Nordmore grid,[44] cetacean entanglement and stranding by switching from floating gillnets to fixed gillnets,[45] and a reduction in turtle stranding’s when TEDs have been implemented.[46]

On the flip side of the coin however, BRDs are not perfect and sometimes negative impacts to the catch can occur. Specific examples include a loss of roughly 6% of shrimp catches on average in the southeastern United States as a result of TEDs[47] and up to 128 tons of shrimp annually in Colombia as a result of BRDs.[48] While evidence of negative impacts abound, the most significant finding in terms of negative impacts of BRDs is the belief that in every situation losses will occur with their implementation, a problem facing small scale shrimp fisheries in India.[49]

Overall, bycatch reduction devices have both positive and negative impacts, this cannot be denied. However, when their implementation is being considered it is important to focus on both sides of the equation so as to factor in the long term health of fisheries to ensure economic prosperity for more than just the short term.

Use and Promotion of BRDs Today

Our understanding and development of new bycatch reduction technologies is rapidly growing as conservation becomes more of a concern for our global fisheries. At the forefront of this research stands many of the developing nations including the United States, Australia, India, and the European Union.[50] With these nations spearheading the use and promotion of bycatch reduction devices, it is becoming easier and easier for them to be implemented in the small artisanal fisheries which make up 90% of the global fishing workforce. Through import and export restrictions such as those imposed by NOAA in the United States, which dictates that seafood imported to the United States must be from fishers utilizing bycatch reduction devices, the bait is on the hook for other nations to follow suit and become involved economically with larger nations.

Potential for Future Work in BRDs

As with all growing fields, there is always the promise of future work in the area of bycatch reduction devices. With increasing technology and increasing demand for food the need to target and capture seafood will become more and more crucial. Along these lines, there lies significant potential in modifications to footrope technologies for bottom trawlers.[51] Modifications here could provide potential increase in catch, reduction in bycatch, and even reduce impact to the seafloor which provides critical habitat for many marine fauna.

References

- ↑ Crespi, V. 2002. Fishing Technology Equipments: Bycatch Reduction Devices (BRD). FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Online.

- ↑ 2011. Management Information: BRDs. Louisiana Sea Grant.

- ↑ 2011. Management Information: BRDs. Louisiana Sea Grant.

- ↑ Crowder, L. B., S. R. HopkinsMurphy, and J. A. Royle. 1995. Effects of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) on loggerhead sea turtle strandings with implications for conservation. Copeia:773-779.

- ↑ Belcher, C. N. and C. A. Jennings. 2011. Identification and evaluation of shark bycatch in Georgia's commercial shrimp trawl fishery with implications for management. Fisheries Management and Ecology 18:104-112.

- ↑ 2011. Management Information: BRDs. Louisiana Sea Grant.

- ↑ 2011. Management Information: BRDs. Louisiana Sea Grant.

- ↑ Pascoe, S. and A. Revill. 2004. Costs and benefits of bycatch reduction devices in European brown shrimp trawl fisheries. Environmental & Resource Economics 27:43-64.

- ↑ Zydelis, R., B. P. Wallace, E. L. Gilman, and T. B. Werner. 2009. Conservation of Marine Megafauna through Minimization of Fisheries Bycatch. Conservation Biology 23:608-616.

- ↑ Larocque, S. M., S. J. Cooke, and G. Blouin-Demers. 2012. Mitigating bycatch of freshwater turtles in passively fished fyke nets through the use of exclusion and escape modifications. Fisheries Research 125:149-155.

- ↑ Fratto, Z. W., V. A. Barko, P. R. Pitts, S. L. Sheriff, J. T. Briggler, K. P. Sullivan, B. L. McKeage, and T. R. Johnson. 2008. Evaluation of turtle exclusion and escapement devices for hoop-nets. Journal of Wildlife Management 72:1628-1633.

- ↑ Hall, S. J. and B. M. Mainprize. 2005. Managing by-catch and discards: how much progress are we making and how can we do better? Fish and Fisheries 6:134-155.

- ↑ Cha, B. J., S. K. Cho, H. C. Ahn, I. O. Kim, and C. Rose. 2012. Development of a bycatch reduction device (BRD) for shrimp beam trawl using flexible materials. Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 11:89-104.

- ↑ Glass, C. W. 2000. Conservation of Fish Stocks through Bycatch Reduction: A Review. Northeastern Naturalist 7:395-410.

- ↑ Melvin, E. F., J. K. Parrish, and L. L. Conquest. 1999. Novel tools to reduce seabird bycatch in coastal gillnet fisheries. Conservation Biology 13:1386-1397.Majluf, P., E. A. Babcock, J. C. Riveros, M. A. Schreiber, and W. Alderete. 2002. Catch and Bycatch of Sea Birds and Marine Mammals in the Small-Scale Fishery of Punta San Juan, Peru

- ↑ Gilman, E., J. Gearhart, B. Price, S. Eckert, H. Milliken, J. Wang, Y. Swimmer, D. Shiode, O. Abe, S. Hoyt Peckham, M. Chaloupka, M. Hall, J. Mangel, J. Alfaro-Shigueto, P. Dalzell, and A. Ishizaki. 2010. Mitigating sea turtle by-catch in coastal passive net fisheries. Fish and Fisheries 11:57-88.

- ↑ Lewison, R. L., L. B. Crowder, and D. J. Shaver. 2003. The impact of turtle excluder devices and fisheries closures on loggerhead and Kemp's ridley strandings in the western Gulf of Mexico. Conservation Biology 17:1089-1097.

- ↑ Eayrs, S., N. P. Hai, and J. Ley. 2007. Assessment of a juvenile and trash excluder device in a Vietnamese shrimp trawl fishery. Ices Journal of Marine Science 64:1598-1602.

- ↑ Eayrs, S., N. P. Hai, and J. Ley. 2007. Assessment of a juvenile and trash excluder device in a Vietnamese shrimp trawl fishery. Ices Journal of Marine Science 64:1598-1602.

- ↑ Queirolo, D., K. Erzini, C. F. Hurtado, M. Ahumada, and M. C. Soriguer. 2011. Alternative codends to reduce bycatch in Chilean crustacean trawl fisheries. Fisheries Research 110:18-28.

- ↑ Queirolo, D., K. Erzini, C. F. Hurtado, M. Ahumada, and M. C. Soriguer. 2011. Alternative codends to reduce bycatch in Chilean crustacean trawl fisheries. Fisheries Research 110:18-28.

- ↑ Vianna, M. and F. D’Incao. 2006. Evaluation of by-catch reduction devices for use in the artisanal pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus paulensis) fishery in Patos Lagoon, Brazil. Fisheries Research 81:331-336.

- ↑ Queirolo, D., K. Erzini, C. F. Hurtado, M. Ahumada, and M. C. Soriguer. 2011. Alternative codends to reduce bycatch in Chilean crustacean trawl fisheries. Fisheries Research 110:18-28.

- ↑ Queirolo, D., K. Erzini, C. F. Hurtado, M. Ahumada, and M. C. Soriguer. 2011. Alternative codends to reduce bycatch in Chilean crustacean trawl fisheries. Fisheries Research 110:18-28.

- ↑ Chosid, D. M., M. Pol, M. Szymanski, F. Mirarchi, and A. Mirarchi. 2012. Development and observations of a spiny dogfish Squalus acanthias reduction device in a raised footrope silver hake Merluccius bilinearis trawl. Fisheries Research 114:66-75.

- ↑ Crawford, C. R., P. Steele, A. L. McMillen-Jackson, and T. M. Bert. 2011. Effectiveness of bycatch-reduction devices in roller-frame trawls used in the Florida shrimp fishery. Fisheries Research 108:248-257.

- ↑ Crawford, C. R., P. Steele, A. L. McMillen-Jackson, and T. M. Bert. 2011. Effectiveness of bycatch-reduction devices in roller-frame trawls used in the Florida shrimp fishery. Fisheries Research 108:248-257.

- ↑ Crawford, C. R., P. Steele, A. L. McMillen-Jackson, and T. M. Bert. 2011. Effectiveness of bycatch-reduction devices in roller-frame trawls used in the Florida shrimp fishery. Fisheries Research 108:248-257.

- ↑ Reference

- ↑ Raborn, S. W., B. J. Gallaway, J. G. Cole, W. J. Gazey, and K. I. Andrews. 2012. Effects of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) on the Bycatch of Three Small Coastal Sharks in the Gulf of Mexico Penaeid Shrimp Fishery. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 32:333-345.

- ↑ Belcher, C. N. and C. A. Jennings. 2011. Identification and evaluation of shark bycatch in Georgia's commercial shrimp trawl fishery with implications for management. Fisheries Management and Ecology 18:104-112.

- ↑ Radzio, T. A. and W. M. Roosenburg. 2005. Diamondback terrapin mortality in the American eel pot fishery and evaluation of a bycatch reduction device. Estuaries 28:620-626.

- ↑ Radzio, T. A. and W. M. Roosenburg. 2005. Diamondback terrapin mortality in the American eel pot fishery and evaluation of a bycatch reduction device. Estuaries 28:620-626.

- ↑ Roosenburg, W. M. and J. P. Green. 2000. Impact of a bycatch reduction device on diamondback terrapin and blue crab capture in crab pots. Ecological Applications 10:882-889.

- ↑ Morris, A. S., S. M. Wilson, E. F. Dever, and R. M. Chambers. 2011. A Test of Bycatch Reduction Devices on Commercial Crab Pots in a Tidal Marsh Creek in Virginia. Estuaries and Coasts 34:386-390.

- ↑ Larocque, S. M., S. J. Cooke, and G. Blouin-Demers. 2012. Mitigating bycatch of freshwater turtles in passively fished fyke nets through the use of exclusion and escape modifications. Fisheries Research 125:149-155.

- ↑ Bury, R. B. 2011. Modifications of Traps to Reduce Bycatch of Freshwater Turtles. Journal of Wildlife Management 75:3-5.

- ↑ Glass, C. W. 2000. Conservation of Fish Stocks through Bycatch Reduction: A Review. Northeastern Naturalist 7:395-410.

- ↑ Glass, C. W. 2000. Conservation of Fish Stocks through Bycatch Reduction: A Review. Northeastern Naturalist 7:395-410.

- ↑ Glass, C. W. 2000. Conservation of Fish Stocks through Bycatch Reduction: A Review. Northeastern Naturalist 7:395-410.

- ↑ Cox, T. A., R. L. Lewison, R. Zydelis, L. B. Crowder, C. Safina, and A. J. Read. 2007. Comparing effectiveness of experimental and implemented bycatch reduction measures: The ideal and the real. Conservation Biology 21:1155-1164.

- ↑ Heales, D. S., R. Gregor, J. Wakeford, Y. G. Wang, J. Yarrow, and D. A. Milton. 2008. Tropical prawn trawl bycatch of fish and seasnakes reduced by Yarrow Fisheye Bycatch Reduction Device. Fisheries Research 89:76-83.

- ↑ Pascoe, S. and A. Revill. 2004. Costs and benefits of bycatch reduction devices in European brown shrimp trawl fisheries. Environmental & Resource Economics 27:43-64.

- ↑ Fennessy, S. T. and B. Isaksen. 2007. Can bycatch reduction devices be implemented successfully on prawn trawlers in the Western Indian Ocean? African Journal of Marine Science 29:453-463.

- ↑ Majluf, P., E. A. Babcock, J. C. Riveros, M. A. Schreiber, and W. Alderete. 2002. Catch and Bycatch of Sea Birds and Marine Mammals in the Small-Scale Fishery of Punta San Juan, Peru

- ↑ Crowder, L. B., S. R. HopkinsMurphy, and J. A. Royle. 1995. Effects of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) on loggerhead sea turtle strandings with implications for conservation. Copeia:773-779.

- ↑ Gallaway, B. J., J. G. Cole, J. M. Nance, R. A. Hart, and G. L. Graham. 2008. Shrimp loss associated with turtle excluder devices: Are the historical estimates statistically biased? North American Journal of Fisheries Management 28:203-211.

- ↑ Maniarres, L., L. O. Duarte, J. Altamar, F. Escobar, C. Garcia, and F. Cuello. 2008. Effects of using bycatch reduction devices on the Colombian Caribbean Sea shrimp fishery. Ciencias Marinas 34:223-238.

- ↑ Sudhakara Rao, G. 2011. Turtle excluder device (TED) in trawl nets: applicability in Indian trawl fishery. Indian Journal of Fisheries 58:115-124.

- ↑ Sudhakara Rao, G. 2011. Turtle excluder device (TED) in trawl nets: applicability in Indian trawl fishery. Indian Journal of Fisheries 58:115-124.

- ↑ Hannah, R. W., S. A. Jones, M. J. M. Lomeli, and W. W. Wakefield. 2011. Trawl net modifications to reduce the bycatch of eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus) in the ocean shrimp (Pandalus jordani) fishery. Fisheries Research 110:277-282.