Template:Statusboxtop Template:Status-Design Template:Boxbottom

Background

There are currently millions of women in developing countries who regularly miss up to 50 days of school and/or work each year as a result of their lack of access to affordable sanitary pads while menstruating. Unfortunately, many women in this situation are unable to afford the premium priced international branded products. As a result, these women are forced to miss school or work. For example in Rwanda, of the girls who miss school, 36% are absent because pads are too expensive.[1] As an alternative, these girls are forced to turn to rags, bark, and even mud. These methods do not adequately contain leakage and more importantly, with limited clean and accessible water supply, these means are unhygienic and potentially harmful.

Females are vital to the development and well-being of their families, communities and countries and should not be hindered to due their natural bodily functions. It is necessary to develop an inexpensive and sustainable product to allow these girls and women to have access to education, good health and employment. An extremely simplified means of using natural fibres to create a pad is describes below.

Basic Banana Fibre Sanitary Pad

The simplest process for utilizing the absorbent properties of banana fibres is outlined in the following steps provided by Hygiene Improvement Project. All photos have been provided by the USAID document. [2] This process is very inexpensive as it requires minimal refinement and preparation of the fibres and therefore does not require any additional materials or machinery.

1) Harvest the Banana Fibre

Cut 1 to 1.5 metre piece from the trunk of a banana tree. It is recommended to strip the trunk early in the morning or in the evening when the fibres are soft.

|

Figure 1: Waterproof inside layer of 2 pieces of banana trunk '

|

Figure 2: Waterproof outside layer of 2 pieces of banana trunk

2) Clean the Fibre

Wipe the fibrous banana sheet with a damp cloth to remove dirt.

3) Straighten the Fibre

Hold the sheet with one hand and pull your other palm along the length of the sheet. Make sure to be firm but gentle.

|

Figure 3: Straightening of banana fibre

4) Peel the Fibre

Carefully peel off the outer layer from the fibre. The outer layer is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 4: Peeling inside layer of fibre

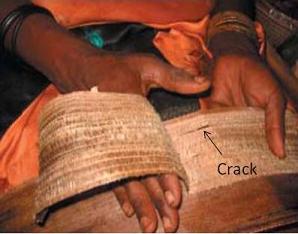

Note: Ensure that the while removing the waterproof outer layer, the fibre does not crack. If the fibre cracks, it will no longer be considered waterproof. Below is an image of a cracked fibre.

|

Figure 5: Cracked fibre

5) Fibre Ready to Use

The banana fibre is ready to use once the entire waterproof outer layer have been removed. This side of the fibre will lie against the skin.

|

Figure 6: Fibre with outside layer removed

6)Use the Banana Fibre

The fibre can now be attached to a belt in front of the belly button. Bring the fibre between legs and attach to the belt above buttocks. The fibre can be attached by either rolling fibre around belt, or by tearing the ends and tying them around the belt.

|

Figure 7: Banana fibre rolled around belt

7)Fibre Disposal

Change fibre as needed. Once used, the fibre can be burned, or disposed of in a garbage bag.

This procedure is a very inexpensive, yet effective way to create a means of capturing menstrual blood. Unfortunately, the popularity of this method is hindered by the obviousness of the fibre. When attached to a belt it is evident to others that the user is in the process of her menstrual period, which is frowned upon in many cultures. Also without refinement of the banana fibre, the pad is very uncomfortable when worn. For this reason organizations such as SHE: Sustainable Heath Enterprises, mentioned below, are taking action and developing an affordable yet practical feminine hygiene pad.

SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises

SHE is a nonprofit organization founded by Havard Business school graduate, Elizabeth Scharpf. The group's first project is intended to enable girls and women in developing countries to set up their own businesses responsible for the manufacturing and distribution of affordable, quality and eco-friendly sanitary pads. The intention is to use local raw materials to ensure accessibility and reduced costs. The product, combined with a sustainable business model operated by and owned by women in the community, will allow the concept to be implemented wherever necessary.

SHE plans to ensure the success of the launch of a local business by:

- Partnering with current local women's networks

- Ensuring the assistance of a microfinance loan for women who will share start-up costs

- Training local groups with the necessary business skills and knowledge in health and hygiene

The group has recently launched their first project in Rwanda. If successful in Rwanda, SHE hopes to expand the initiative across Africa and into South-East Asia and Central America.

If you would like further information or wish to support SHE, the official website can be accessed at SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises.

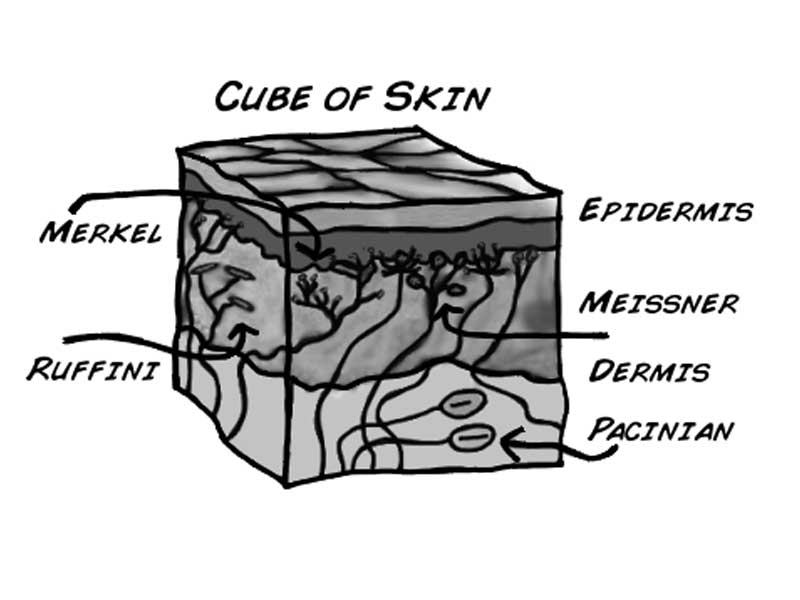

Engineering Principles

Material Selection

The most common material used by major manufacturers in the production of feminine hygiene products is wood fibre. The fibres are fluffed to ensure that the product is absorbent and soft. In addition, advanced gels have been introduced to increase the product's absorption capacity. These materials are then combined with an a polypropylene top layer to provide comfort and an exterior polyethylene leak proof shell.[3] The use of these advanced materials cause the product to be too expensive for many females in developing countries. As a result, SHE has done extensive research in order to determine an absorbent alternative. SHE has chosen to utilize the absorbent qualities of banana tree fibres. Banana trees are harvested every 9 months and normally the fibres found in the trunks are thrown away by farmers. By using the fibres in the local production of feminine hygiene pads, farmers will be able to harvest this waste material in return for a profit. Also by using a product that is produced locally, rather than importing a more expensive product, the cost of the hygiene pad is reduced significantly.

Material Extraction

Banana fibres can be extracted in a variety of ways by employing chemical, mechanical or biological methods. Based on past findings, chemical methods tend to cause environmental harm and biological methods require at least a month before the fibres can be retrieved. The mechanical method, however, is straight forward and inexpensive and has been popularized in developing nations.

The outer sheath of the trunk is composed of tightly covered layers of fibre. The fibre is primarily located adjacent to the outer layer and can be peeled off in strips of 5 to 8 cm wide and 2-4 mm thick.[4] The stripping process is known as tuxying the strips, which are referred to as tuxies. Once the tuxies are stripped from the sheath, they are bundled and brought to the stripping knife for cleaning. In this process, the tuxies are pull under a knife blade. The blade is pressed tightly against a wood or stone block in order to scape away the plant tissue between the fibres. The bundles of clean fibres are then hung to dry. Basic machines can also be used as an alternative to hand stripping. They consist of two rolls, of which one is fitted with a scrapping blade. Once the darker outer sheath has been removed from the trunk, it is cut into sections of approximately 120 to 180 cm in length. These sections are fed through the revolving drums. The scrapping blade scrapes the pulpy tissue away. The pulp can then be dried and used in the same manner as the tuxies.

Manufacturing Process

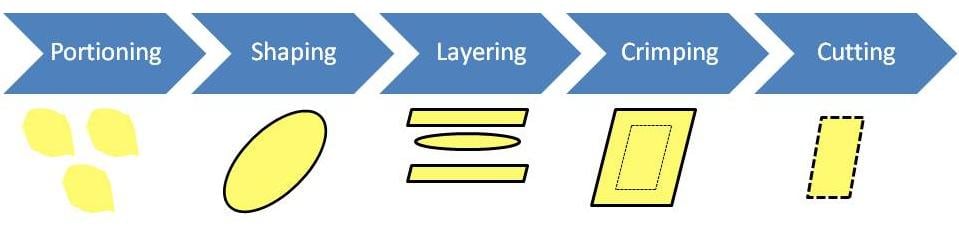

Once the fibres have dried, they are ready to undergo the manufacturing process. Students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology worked alongside SHE to determine an effective way of manufacturing pads from banana fibres. They broke down the process into the following sub-processes.

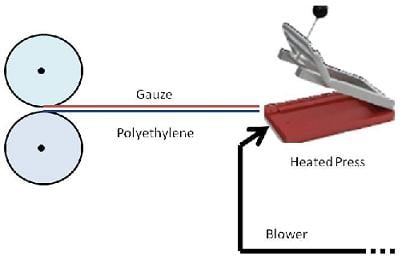

In order to satisfy these subprocesses, the MIT students developed a manufacturing process known as Komera, which can be found in their brochure, Komera: Strength for Women. The process detailed in the brochure requires the participation of 2 labourers. The procedure portrayed in the video filmed by the MIT students are summarized by the following steps:

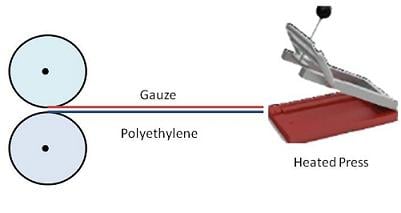

1) Labourer #1 pulls the polyethylene and gauze from the rollers and layers them over the press and then folds down the top part of the press.

2) Labourer #1 then inserts the fibre blower into the open end of the layers and flicks a switch, which activates the heating of the press and the blower.

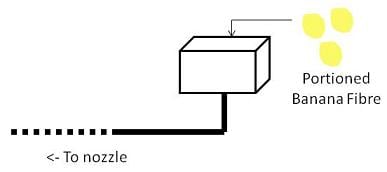

3) Labourer #2 portions enough banana fibre for 1 pad and inserts it into the chute at end of blower. It should be noticed that the subprocess 'layering' has been ignored as it is unnecessary.

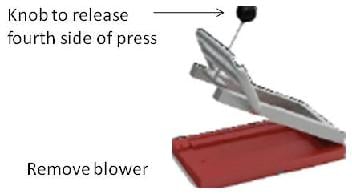

4) When the pad is full, labourer #1 flicks the switch off and removes the blower's nozzle. The labourer then modify the press to include a 4th side and flick another switch to seal the final side of the pad.

5) Labourer #1 lifts press and is then able to rip pad from the sheets of gauze and polyethylene.

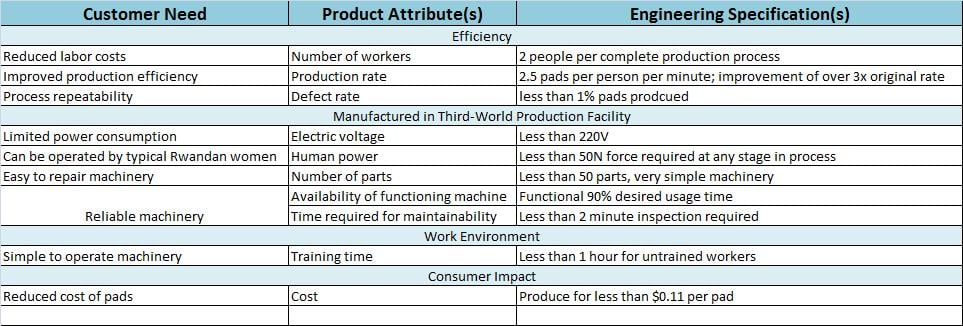

This process was designed to meet the needs of Rwandan women, which were determined by SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises. The needs and the means used to meet these requirements are outline in the following table.

Material Alternatives

The material alternatives available for this product will focus on natural fibres. This choice in material allows for a reduction in cost, a greater likelihood of local availability and results in an eco-friendly product, if produced properly.

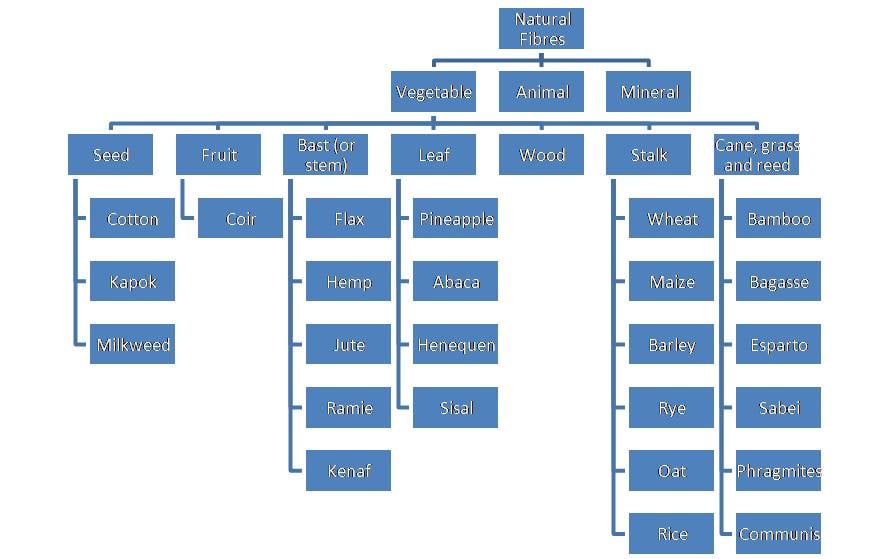

Natural fibres are subdivided based on their origin-whether they are derived from plants, animals or minerals. The primary focus of this material analysis will be plant based fibres as they have a high moisture absorption. Also, these fibres will be more accessible as they are more likely to otherwise go to waste, whereas animal fibres such as fur, or mineral fibres such as asbestos, can be used for more profitable applications other than female hygienic pads.

The following figure displays the most abundant plant fibres.

The following table demonstrates moisture content of common vegetable fibres. This value indicates the amount of water content the dried fibres will be able to absorb. A higher water content value indicates a higher absorption value and would therefore be beneficial when used in a hygienic pad.

The moisture content of a given material is calculated using the following equation:

| Fibre | Moisture Content (wt%) |

|---|---|

| Flax | 8-12 |

| Hemp | 6.2-12 |

| Jute | 12.5-13 |

| Kenaf | ---- |

| Ramie | 7.5-12 |

| Nettle | 11-17 |

| Sisal | 10-22 |

| Henequen | ---- |

| PALF (Pineapple) | 11.8 |

| Banana | 10-12 |

| Abaca | 5-10 |

| Cotton | 7.85-8.5 |

| Coir | 8 |

Based on the data provided above, the moisture absorption level of most of the plant fibres are comparable to that of cotton fibres, which are most commonly used in hygienic pads, as well as banana fibres, which are the baseline material selected for use in developing nations. The other materials listed above will be investigated further to determine their feasibility as the absorbent centre of the pad.

Bast Fibres

The shape and size of the stems of various bast fibre crops are different but each contain a varying amount of fibres.

Flax Fibres

Flax is a bast fibre grown in temperate climates. Flax is currently used for many application including linens, paper and pulp. The product is commonly grown in Europe, Argentina, India and China. Unfortunately, flax fibres are expensive due to the many labour-intensive production steps associated with its refinement.[6] For this reason flax fibres are more suitable for use in products such as automobiles rather than low-cost hygienic pads.

Hemp Fibres

Hemp is a native to Central America and consists of both a male and female plant. The male plants ripen earlier and therefore must be harvested earlier while the female plants are more highly branched and bear denser foliage. The male plants yield fairly fine fibres while the female plant is preferred by the pulp and paper industry. The hemp fibres are fairly easy to harvest, however, due to their higher wax content they are resistant to water. This characteristic reduces its potential effectiveness for use in a pad.

Jute Fibres

Jute fibres are a native to the Mediterranean region and have expanded throughout the Near and Far East. Jute is among the most versatile, ecofriendly, natural and durable fribre. Today, most jute is produced in India, Bangladesh, Thailand, China and Brazil. Jute is the most hygroscopic plant fibre as it has little resistance to moisture absorption.[6] This characteristic makes jute ideal for use in hygienic pads. Unfortunately, jute is grown entirely for its fibres, which are currently used in a variety of industries. Therefore, it may difficult and expensive to acquire jute for use in an inexpensive pad.

Kenaf Fibres

Kenaf is a canelike crop which is produced primarily in Asia and Africa. The plant contains two fibres: long fibres situated in the cortical layer and short fibres situated in the ligneous region. The fibres have not yet been popularized but have potential for use in the paper, textile and composite industries. Kenaf's absorbent features and presence in various locations across Africa make it a feasible material.

Ramie Fibres

Ramie is cultivated mainly in Indonesia, China, Japan and India. the fibres have been used in the textile industry for centuries due to their excellent fibre characteristics. The fibres are very fine and silk-like. A main characteristic of interest is their good resistance to bacteria, mold and insect attack.[6] The primary application of ramie fibres is their use in the production of biodegradable plastics.[7]

Nettle Fibres

Nettle is a plant which contains nonlignified bast fibres in the bark. A drawback of the wild Nettle is its ability to yield only 3-5%.[8] The fibres are generally used as reinforcing fibres for polymer composites and will not be considered for hygienic pads.

Leaf Fibres

Sisal Fibres

Sisal is a native to Mexico and Central America but can now be found in tropical countries in Africa and the West Indies. Sisal is one of the 4 most commonly used plant fibres in the world. It is primarily used as a polymer reinforcement for the interior of cars. As Sisal fibres are already used in an industry as dominant as the automotive industry, it would be difficult to justify, economically, its use in sanitary pads.

Henequen Fibres

Henequen is a close relative of the sisal plant and similarly it is primarily used in the manufacturing of textile products. Today, the Henequen fibres are produced in the tropical regions of Africa, Central and South America and Asia. Henequen fibres are produced in many of the countries into which SHE: Sustainble Health Enterprises has expressed interest with regards to product expansion. Unfortunately, due to the fibres high wax content, it is most likely not suitable as an absorbent material.

Pineapple Leaf Fibre (PALF)

Pineapple is cultivated primarily for its fruit. The pineapple bran, the fruit residue after juicing, is high in vitamin A and is generally used to feed cattle. The leaf, however, is normally unused and harvests the pineapple leaf fibres. The plant is largely cultivated in tropical countries. The leaves are about 91 cm long, 5 to 7.5 cm wide and sword shaped.[6] From the leaves, strong and silky fibres can be removed. The fibres are very hygroscopic and would prove very feasible for use in hygienic pads.

Banana

Similar to pineapples, bananas are primarily cultivated for fruit. The fibres are harvested from the plant's trunk, which are normally unused and go to waste. Small pieces are subjected to softening and then normally undergo mechanical extraction, as mentioned above. Banana fibres are primarily harvested in India, Indonesia and the Philippines and now in bangladesh

Abaca

The abaca plant is a close relative to the banana tree. It is cultivated primarily in the Philippines but has been introduced to Indonesia and Central and South America. Abaca is a hard fibre that is obtained from the leaf sheaths. The fibres are commonly used for ropes, and hadicraft goods. The fibres would be feasible as an absorbent material, however, due to its primary growth locations, this fibre should only be considered upon expansion to South East-Asia or South America.

Cotton

Cotton is an ideal fibre for use in hygienic pads. It is currently used in many female hygienic companies in North America. Unfortunately, due to its high demand in a variety of industries the cost of cotton is too expensive for this project.

Coir

Coir fibres are harvested from coconut husks in Sri Lanka and India. The coir fibres are obtained after the husk undergoes a retting process. The fibres are resilient, strong and highly durable. Coir fibres are unique in the way they are naturally insulating, sound absorbent, antistatic, and difficult to ignite. For theses reasons, coir is primarily used in the textile and automotive industry. Recently, the academic and industrial R&D communities have begun to seek ways of further utlizing coir fibres' unique characteristics.[6]

The majority of the fibres listed above are in demand by more prominent industries including the automotive, polymer and composite sectors. With this in mind, the production of low-cost, eco-friendly hygienic pads should only consider fruit based plant fibres as their absorbent core. Both pineapple and banana trees are primarily harvested for their fruit and the fibres contained within the leaves and trunks, respectively, go to waste. The collection of fibres from the waste of these plants not only assists with the manufacturing of pads, but also provides economic stimulus to the fruit farmers.

Regional Considerations

Pineapple and banana plants are only able to grow in tropical climates. Therefore, the plants are obviously unable to be produced worldwide. As SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises mentions on their webpage, the organization plans to expand their efforts throughout Africa, South America and South-East Asia. These efforts rely on the availability of resources in each expansion location, such as the natural plant fibres required for the absorbent centre of the pad. The availability of plants in these areas, such as banana plants and pineapple plants, will be investigated in the following section.

Pineapple Plant

Pineapples are produced in 82 countries around the world. They are naturally drought tolerant and can grown in seasonal wet/dry areas of the tropics that normally do not support less water efficient crops. The following tables display the countries in which pineapples are produced in large quantities.

| Country | % of World Production |

|---|---|

| Thailand | 11% |

| Philippines | 11% |

| Brazil | 10% |

| China | 10% |

| India | 9% |

| Nigeria | 6% |

Pineapples can also be cultivated in most tropical countries. Some of these countries include, but are not limited to,

- Costa Rica

- Mexico

- Indonesia

- Kenya

- Venezuela

- Colombia

- Guatemala

- Ivory Cost

- Cameroon

- Democratic Republic of Congo

The pineapple plant is readily available in many countries in South America, South-East Asia and Africa. Therefore, after harvesting the fruits from the plants, the wasted leaves can be refined for use in sanitary pads.

Banana Plant

Bananas grown in tropical regions and require moist soil with good drainage. It has been estimated that bananas are currently being grown in approximately 101 countries around the world. [10] The following table displays the countries in which bananas are produced in large quantities.

| Country | % of World Production |

|---|---|

| India | 21% |

| Brazil | 9% |

| China | 9% |

| Philippines | 9% |

| Ecuador | 8% |

| Indonesia | 7% |

Bananas can also be cultivated in most tropical countries. Some of these countries include, but are not limited to,

- United Republic of Tanzania

- Costa Rica

- Thailand

- Mexico

- Burundi

- Guatemala

- Viet Nam

- Kenya

- Bangladesh

- Egypt

Similarly, banana plants are cultivated in many countries among South America, South East-Asia and Africa. Once the fruits have been harvested, the wasted trunks can be used to generate fibres for use in hygienic pads.

Manufacturing Alternatives

As mentioned earlier, the subprocesses associated with the manufacturing process of the hygienic pads is as follows:

- Portioning

- Shaping - has been proven unnecessary

- Layering

- Crimping

- Cutting

Portioning

The portioning can be done by a labourer. Prior to production, a standardized amount must be determined and explained to the labourer. Due to the nature of the product, slightly more or less of the absorbent material will not result in failure of the product.

Layering

The process deisgned by the Massachusetts Institue of Technology used a blower to transfer the portioned absorbent material to the inside of the shell created by polythylene and gauze. A typical blower uses a fan to transport material from end of the tubing to the nozzle. For this type of application the horsepower required to power the fan is minimal. Based on the Air Movement and Control Association International (AMCA), a Fan Class I would be sufficient. [11] To determine the power required by such a fan or blower the following equation is used.

Where,

- P is the power consumption (W)

- Q is the air volume flow rate delivered by the fan (m3/s)

- p is the total pressure (Pa)

- is the fan efficiency

For simplicity it will be assumed that this application would use a motor in the range of 1 kW. Although this is not significant source of power, there is still a cost associated the addition of the mechanical system to the manufacturing process as well as an operational cost. An alternative to the blowing system is to shape the fibres manually.

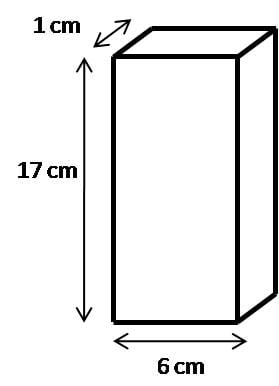

After the fibres have been portioned, they can be molded with the use of a mold cavity. The portions will ideally fill the cavity with enough fibres to provide adequate absorption. The shape of the pad is a simple rectangular cube, therefore the cavity could be made from anything include wood, scrap metal, etc. The mold will consist of 4 walls with either a base of the mold should be used on a hard, flat surface. The mold should be formed to the following dimensions. These dimensions are based on the size of typical commercially available female hygienic pads.

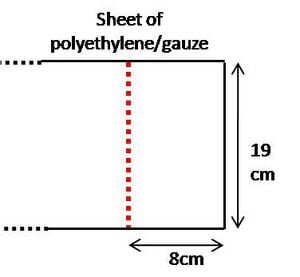

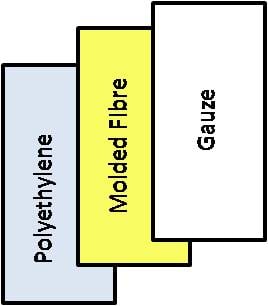

The initial design by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggested having the polyethylene and gauze on rollers. This would allow the labourer to pull the sheets and lie them over the appropriate area of the heated press. This system, along with the design of the heated press, was successful alongside the use of the blower to fill pad's centre. Since the blower has been removed from the process, and the fibres are formed manually, a new system is required for the layering of the polyethylene, gauze and fibres. The polyethylene and gauze sheets used in this production are thin enough to be ripped manually. Each of the sheets should be ripped to a pre-determine size. The polyethylene sheet is used as the waterproof bottom layer, followed by the absorbent fibres, and finally the gauze top layer. The arrangement of materials can then be moved to the 4-sided heated press.

Crimping

The 4 sided heated press will be use to bond the gauze and the polyethylene to contain the fibres. Polyethylene is a thermoplastic and used as an adhesive once heated. When a thermoplastic is heated to a sufficiently elevated temperature, it is easier to mold and form into desired shapes. The increased temperature weakens the secondary bonds, and thus the adjacent chains can move more freely under shaping forces. Once the plastic is cooled, it remains in the shape but regains its original hardness and strength.[12] Polyethylene has a melting point at approximately 70 ⁰C.[13] The heated press will need to be heated to at least 70 ⁰C in order to guarantee melting of the polyethylene sheet. Once the sheet is melted, the plastic is intertwined with the threads in the gauze. Upon cooling, the plastic hardens around the threads creating an adhesive. It is also convenient that the majority of thermoplastic material, including polyethylene, are waterproof.

Alternatives to Polyethylene

There are many thermoplastics available for commercial use. Some of the more common thermoplastics, along with their maximum temperature, are listed in the table below.

| Thermoplastic | Common Acronym | Maximum Temperature Limit (⁰C) |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene | ABS | 80 |

| Polyvinyl Chloride | PVC | 65 |

| Chlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride | CPVC | 100 |

| Polyethylene | PE | 70 |

| Cross-Linked Polyethylene | PEX | 100 |

| Polybutylene | PB | 100 |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride | PVDF | 150 |

Table 5: Common thermoplastics[13]

Polyethylene was chosen as the waterproof barrier due to its low melting point as indicated in the above table and its low cost.

Cutting

The cutting subprocess is no longer required as the materials are manually cut prior to entering the heat press.

Final Manufacturing Process

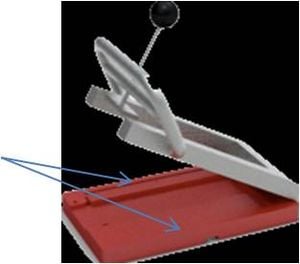

| Step | Picture | Description |

| 1) |  |

From the bin if collected fibres, remove enough to fill quota required per pad as determined by SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises. If interested in exact quantity please contact a member of SHE at their website: SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises |

| 2) |  |

Use the allotted fibres and fill the mold to create a 17 cm x 6cm rectangle that is 1 cm thick. |

| 3) |  |

Cut/Rip a 19cm x 8cm section from both the gauze and polyethylene sheets. |

| 4) |  |

Layer the waterproof polyethylene, absorbent fibres, and gauze. Ensure that the fibres are centred within the boundaries of polyethylene/gauze sheets. |

| 5) |  |

Place the polyethylene, fibre, gauze arrangement on the heating press. Clamp press to bond the polyethylene and gauze together. |

| 6) |  |

Final Product! Image provided by:SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises |

Estimated Cost

An economic analysis is difficult to perform. The exact types of polyethylene and gauze sheeting are undefined. The cost of polyethylene sheets varied from $10.00-$12.59 for sizes of approximately 10 ft x 25ft. [14] The cost of gauze sheets are difficult to find as gauze is normally sold for medical purposes and is therefore cut into small squares. This type of gauze is high grade and sterilized. The prices associated with this product are expected to significantly exceed the price of lower grade gauze.

The fibres used as absorbent centre of the pad are nearly impossible to price. The concept of using waste product from fruit trees is a relatively new idea and has not yet been popularized. Therefore, the price per bundle varies based on the type of fibre and location selected and the level of knowledge of the fruit farmers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Unfortunately throughout the course of this project, SHE: Sustainable Health Enterprises was unable to provide any information concerning their current material selection or manufacturing process. The organization is currently in the process of refining their material selection, as well as optimizing the manufacturing process for execution in Rwanda. Regardless, the information provided above should prove useful to the organization and the advancement of low-cost, eco-friendly feminine hygiene pads.

References

- ↑ "Our Initiatives." She : Sustainable Health Enterprises. 2008. Web. 05 Apr. 2010. <http://www.sheinnovates.com/ourventures.html>.

- ↑ Plan. Hygiene Improvement Project. Publication no. Unit 6: Menstrual Period Management. USAID. Print.

- ↑ Kotex® – Pads, Tampons, Feminine Care and Period Protection. Kimberly-Clak Worldwide, 2010. Web. 06 Apr. 2010. <http://www.kotex.com/na/default.aspx>.

- ↑ Mott, and MacDonald. "Banana Fiber Extraction and Processing up to Textile." Guharat Agro Industries Corporation Ltd. Web. 13 Apr. 2010. <http://www.gujagro.org/agro-food-processing/banana-fibre-processing-13.pdf>.

- ↑ "Product Contract - Banana Leaf Pad Assembler." Product Engineering Process Gallery. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Web. 13 Apr. 2010. <http://designed.mit.edu/gallery/data/2009/tech/extras/Yellow_product_contract.pdf>.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Mohanty, Amar K., Manjusri Misra, and Lawrence T. Drzal, eds. Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites. Boca Rato, FL: Taylor & Francis, 2005. Print.

- ↑ Wallenberger, Frederick T., and Norman Watson, eds. Natural Fibers, Plastics and Composites. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic, 2004. Print.

- ↑ Mohanty, Amar K., Manjusri Misra, and Lawrence T. Drzal, eds. Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites. Boca Rato, FL: Taylor & Francis, 2005. Print.

- ↑ "Pineapple - Ananas Comosus." Fruits. University of Georgia. Web. 14 Apr. 2010. <http://www.uga.edu/fruit/pinapple.html>.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Production: Crops." FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Web. 14 Apr. 2010.

- ↑ "Fan Class Limits-AMCA." The Engineering Toolbox. 2005. Web. 15 Apr. 2010. <www.engineeringtoolbox.com/fan-amca-class-d_911.html>.

- ↑ Kalpakjian, Serope, and Steven R. Schmid. Manufacturing Engineering and Technology. 4th ed. Upper Saddler River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. Print.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Thermoplastics - Physical Properties." The Engineering Toolbox. Web. 15 Apr. 2010. <www.engineeringtoolbox.com/physical-properties-thermoplastics-d_808.html>..

- ↑ "Poly Film 10X25Ft 4Mil Clear By Warp Brothers" Hardware Harbor.Web. 4 Apr. 2016. <http://www.hardwareharbor.com/Poly-Film-10X25Ft-4Mil-Clear-By-Warp-Brothers_p_13389.html>.