What Are Biosolids?

During the process of waste water treatment, solids and semisolids composed mainly of organic material are collected from the waste water, digested, and poured into drying beds (Figure 1). These solids are defined as biosolids by the Environmental Protection Agency[1]. Biosolids can be recycled as soil amendment and or fertilizer due to having nutrients and metals that soils tend to lack.[2]

Categories of Biosolids

Biosolids can be categorized into either Class A Unrestricted (exceptional quality), Class A restricted, or Class B restricted. Both Class A biosolids, unrestriced and restriced, are sold to the public for home use. When sold, Class B biosloids are used for agriculture and landscaping, in areas of limited public contact. The reason that only Class A biosolids are sold to and used by the public is because they have fewer pathogens which lead to potential harm. For more information regarding the technical differences between Class A and Class B biosolids refer to page six of the 503 regulations.

How Biosolids are Categorized at Arcata Marsh

Seven samples of the biosolids are taken at two different times to be tested for heavy metals and pathogens[3]. The biosolids are tesed first when they are poured into the drying beds, and again after they have been composted. Each time a test is run, seven samples of the biosolids are taken by the City of Arcata to North Coast Labs.[4]

| Heavy Metals Tested for | |

|---|---|

| Arsenic | Mercury |

| Cadmium | Molybdenum |

| Chromium | Nickel |

| Copper | Selenium |

| Lead | Zinc |

| Pathogens Tested for |

|---|

| Fecal Coliform |

| Salmonella |

To meet Class A standards for exceptional quality, fecal coliform counts must be less than 1000 MPN (Most Probable Number) per gram of dried biosolids[5]. Also the salmonella levels must be less than three MPN per gram of biosolids, according to the EPA[2]. The criteria differentiating Class A and Class B biosolids in relataion to heavy metals can be found in the 503 regulations on page seven.

Where and How Biosoilds are Dried

Biosoilds are poured into drying beds which are a set of two rectangular cement floored holding areas that have drains. To get an idea of how large they are, look at (Figure 1) and compare the bed to the Ford truck in the background. It is in the drying beds that evaporation and transpiration (evapotranspiration) act as the drying mechanism of the biosolids[6]. The hotter and sunnier the year is, the faster the biosolids harden into a dirt-like consistency. Built above the drying beds is a metal roof with air vents and skylights, viewable in (Figure 3). Because Arcata gets rain for a majority of the year, this roof helps the biosolids from getting watered down or inundated. Drying can take anywhere between six months to one year. Each year at Arcata Waste Water Treatment Plant two dry beds of biosolids are generated (Figure 2).

Purpose of Composting

Waste water treatment plants such as Arcata Marsh produce large amounts of biosolids. The biosolds initially have high pathogen counts, for example: more than 1,000 MPN fecal coliform per gram biosolids. Composting is used to kill human and plant pathogens as well as balance out the pH to roughly 7. To make the biosolids meet Class A exceptional quality they are composted.

How the Compost is Made

After the biosolids are done drying, one part biosoilds is mixed with three parts [1] and two parts [2] inside the mixing machine (Figures 4 and 5)[7]. This mixture of 3 parts wood wate, 2 parts green waste, 1 part biosolids provides the correct carbon to nitrogen ratio (around 30:1), helping promote optimal decomposition[8].

Method of Composting Used

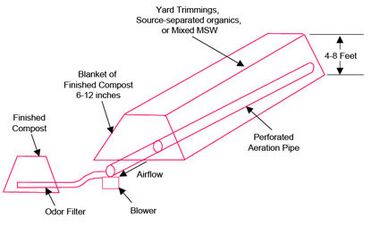

The mixture is dumped into a series of long piles. Each pile sits on top of a large air vent pipe (Figures 7 and 8). This air vent pipe can either feed oxygen to the microorganisms or take it away. Adding oxygen to the pile will raise the piles temperature due to increased microorganism activity. This method of composting is known as aerated static pile composting[1]. A diagram of aerated static pile composting can be seen in (Figure 6).[9]

Temperature Phases of Composting at Arcata Marsh

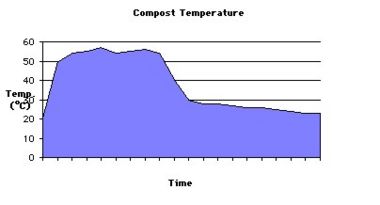

To make sure harmful human and plant pathogens are killed, compost must be held at high temperatures for designated time periods (Figure 9). A pile with a high temperature reflects an abundance of microbial digestion. By pumping oxygen into the compost piles, site workers are able to keep the piles at a maintained high temperature of 46.1 degrees Celsius for 14 days and 55 degrees Celsius for three days[3]. After the compost piles have been through the highest of temperature phases (55 degees Celsius for three days) they are once again tested, and each year qualify as Class A.

Microorganisms of Composting

Each pile of compost has within it a number of different microorganisms. Each type of microorganism takes part in the decomposing process, some during certain temperature phases only. While the aerated static compost pile sits, mesophilic bacteria and fungi start decomposing organic material. Mesophilic bacteria decompose organic material only in the first and last phase of composting, when the temperature of the compost pile is less than 40 degrees Celsius. A large population of invertebrates aid in this phase of decomposition as well[10]. Some examples of invertebrates include: Ants, beetles, worms, and mites. Invertebrates decompose the larger particles in the compost, making work for the bacteria and fungi easier. As the temperature of the compost exceeds 40 degrees Celsius thermophilic bacteria take over decomposing for the mesophilic bacteria and invertebrates. Actinomycetes are another decomposer of the pile[11]. These are a major contributing factor to the smell of compost and can be seen on the surface of the pile appearing as a spider's web. It is the combination of microorganisms that makes composting possible.[8] [12]

Potential Dangers of Biosolids and Compost

When handling biosolids and or compost, people are exposing themselves to a number of potential dangers. If ingested, both biosolids and compost contain a large number of pathogens, which could cause disease and possibly death. Skin, eye, and respiratory protection in many situations are required, especially when handling Class B biosolids. One disease known to be caused by the bacteria in compost is legionnaires ‘disease. Another potential danger is actinomycosis, a disease caused by Actinomyces israelii. These two types of diseases are related to human inhalation and or ingestion of compost. Keeping that in mind, the people who handle biosolids and compost at Arcata Marsh wear protective gear, masks, and wash up after working. As long as one doesn't ingest/inhale compost or biosolids, chances of getting sick are minimal. Another danger involved with composting on such a large scale is the operation of heavy machinery (Figure 10). OSHA has set safety standards for facilities such as Arcata Marsh.[13][14]

Current Uses

Each year Arcata Waste Water Treatment Plant generates only a few piles of compost. Instead of selling it to the public, the City of Arcata gives the compost to the Park and Recreation Department. There the compost is spread about in the local parks and or recreation areas.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Environmental Protection Agency

accessed 25 Oct. 2008

http://www.epa.gov/region8/water/biosolids/

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "EPA" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.epa.gov/region8/water/biosolids/biosolidsdown/Biosolids%20Inspection.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Neander, Julie. City of Arcata. e-mail ref. 22 Oct.2008

- ↑ North Coast Labs. 28 Oct. 2008 http://www.northcoastlabs.com/index.asp

- ↑ Lindquist, John. "The Most Probable Number Method." Department of Bacteriology at University of Wisconsin. 15 June. 2008. accessed 26 Oct. 2008. http://www.jlindquist.net/generalmicro/102dil3.html

- ↑ Burba, George (Lead Author); Jason A. Hubbart and Michael Pidwirny (Contributing Authors); Judith S. Weis and Daniel Robert Taub (Topic Editors). 2006. "Evapotranspiration." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). [First published in the Encyclopedia of Earth October 19, 2006; Last revised November 7, 2006; Retrieved October 27, 2008]. http://www.eoearth.org/article/Evapotranspiration

- ↑ “Organic Waste Definitions.” Ciwmb.ca.gov. 29 Aug. 2008. California Integrated Waste Management Board. 27 Oct. 2008 http://www.ciwmb.ca.gov/organics/Definition.htm/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Newbery, Ricardo and Tatum, Tammy and Reynolds, Dave and White, Gary. Digital Seed.com. 25 Feb. 1999 accessed 28 Oct 2008 http://www.digitalseed.com/composter/biology/bacteria.html http://www.digitalseed.com/composter/biology/fungi.html http://www.digitalseed.com/composter/science/cnratio.html

- ↑ City of Arcata. Environmental Services. 28 Oct. 2008. http://www.arcatacityhall.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=25&Itemid=52#green

- ↑ Trautmann, Nacy and Olynciw, Elaina. "Compost Microorganisms." Cornell Composting Science and Engineering 28 Oct. 2008 http://www.css.cornell.edu/compost/microorg.html

- ↑ Wassenaar, Dr. T.M and Blazer, Dr. M.J. "Actinomycetes spp." bacteriamuseum.org. 6 Feb. 2003. Virtual Museum of Bacteria. 27 Oct. 2008 http://www.bacteriamuseum.org/species/actinomycetes.shtml

- ↑ Barbarick, K.A. "Organic Materials as Nitrogen Fertilizers." Colorodo State University. ext # 0.546. 25 Oct. 2008 http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/crops/00546.html

- ↑ U.S Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 28 Oct 2008. accessed 28 Oct. 2008. http://www.osha.gov/

- ↑ Madeley, Gavin. "How you can catch deadly legionnaires' disease from garden compost." dailymail.co.uk. 24 May. 2008. Mail Online. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1021542/How-catch-deadly-legionnaires-disease-garden-compost.html

See Help:Footnotes for more.