In early years, as well as in developing areas, humans did not have the technology to ventilate their buildings through mechanical and electrical components. Yet, they were able to sufficiently provide ventilation by designing their buildings in such a way that would allow for decent ventilation without any electricity or power.

As the name suggests, natural ventilation involves the exchange of air between the inside and outside of a building through natural methods. This approach often utilizes naturally available forces, such as wind and pressure. By implementing natural ventilation, plenty of electricity can be saved with little to no decrease in internal air quality, provided the building is designed in a suitable manner. Furthermore, without using as much energy, fewer emissions are released into the atmosphere, helping to prevent further damage to the environment.

The scope of this project involves conducting thorough research on existing studies done on natural ventilation, as well as determining the most suitable design based on location, as well as other external factors.

Background[edit | edit source]

At any given moment in time, there are air streams flowing all over the planet at certain pressures, dependent on altitude and temperature. When there are differences between the pressures of these air streams, wind is formed as air flows from an area of higher pressure to lower pressure. At greater altitudes, the velocity of the wind is higher, whereas near the ground, due to friction, the velocity is lower.[2]

Types of natural ventilation[edit | edit source]

Being dependant on natural forces, there is obviously more than one way to apply natural ventilation. The first option makes use of wind forces, while the second option relies instead on air temperature differences and buoyancy (known as the stack effect).

Wind-driven ventilation[edit | edit source]

Using natural air to ventilate a building is not only less expensive, but also less damaging to the environment thanks to the utilization of equipment that consumes a much lower amount of energy than mechanical systems. With a properly designed building, using natural wind could result in ventilation quality that is just as high as what could be achieved with a system that consumes more energy.

When wind collides with a building, different pressures are observed from different sides of the building. The side that the wind is blowing into would have a higher air pressure than the opposite side; this would cause the air on the side with the higher pressure to flow to an area of lower pressure, which in this case would be the building's interior.[3] Another opening on the low pressure side would allow the interior air to circulate outwards to the side with the lower air pressure.

To improve the flow of air through a building, a wind catcher may be utilized at the building's opening to better direct the incoming air. Wind catchers have been used to naturally ventilate buildings for the past few centuries, and are generally quite efficient in improving air circulation throughout the building. Figure 3, seen below, shows the effect a wind catcher would have; as the wind blows towards the closed side of the building, it must flow around it, and as it passes the opening, drags the air from inside the building outwards as well. This is known as the Coandă effect,[5] which is very commonly seen when the flow of a fluid is distorted as it flows past an object; the fluid is attracted to the surface of the object. In this manner, fresh air is constantly supplied throughout the building. It should be noted that many wind catchers can be controlled to open and close at different sides to suit the direction of the travelling wind.

Stack-driven ventilation[edit | edit source]

The stack-effect,[8] as briefly mentioned above, is based on the fact that warmer air rises as cooler air falls. This is due to differing densities; when air is heated, it becomes less dense, allowing it to rise, pushing cooler air downwards. Creating an upward air stream, this concept is very important in the stack-driven method of ventilation.

In order for this method to work, the climate must be right, meaning the interior of the building should contain warmer air than the air outside. With openings at the lower levels and top of the building, the warm air inside would rise and leave the building through the openings at the top, while cooler air from outside would flow in through the openings near the bottom. A greater temperature difference would make this system very effective. Once again, Figure 2 above shows this phenomenon in action in conjunction with a wind-driven system; the cool air enters the building at the lower level of the building as the warmer air from inside is forced out through the skylight.

Furthermore, pressure is also involved in the stack effect. At the point in between the warm and cool air is the area of neutral pressure; any point below this would be at a lower pressure, thus drawing in the air from the outside. Above the neutral pressure line, the pressure is higher, forcing air out through openings near the top into lower pressure areas outside. Figure 4 below illustrates this.

Advantages and Disadvantages[edit | edit source]

Because wind and stack driven ventilation commonly go hand in hand in natural ventilation systems, it is difficult to find disadvantages. However, when the two are separated, each method does have its own drawbacks, as well as advantages.

Wind-driven ventilation[edit | edit source]

Advantages:[3]

- Relies on natural force (wind)

- When it works, it works to a very high magnitude

- Suitable for most areas in the world, as wind is all over the planet

- Relatively inexpensive

- Fewer emissions, as less energy is consumed

Disadvantages:[3]

- Uncontrollable factors, such as speed and direction of wind

- Can bring polluted air into buildings

- Strong winds would result in cooler temperatures that can not be controlled

Stack-driven ventilation[edit | edit source]

Advantages:[3]

- Does not require wind; can work even when the surrounding air is completely still

- Relies on natural force (pressure and temperature differences)

- More control with regards to where the openings in the building are

- Uses almost no energy compared to conventional methods, saving money and the environment

Disadvantages:[3]

- Cannot control exterior temperature

- Can bring polluted air into buildings

Design considerations[edit | edit source]

Because building design is crucial for natural ventilation to be effective, there are many considerations that must be taken into account when constructing a building that will be using natural ventilation. A few of these are listed below.[3][10]

- Location

- Building Orientation

- Dimensions

- Opening (ie. windows, doors, chimneys) placement, and ensuring these openings are not obstructed

- Wall placement

- Wind direction

- Depth under the ground the building is built at

- Thermal capacity

Ideally, a building utilizing natural ventilation should have openings in lower levels, as well as near the top. This would allow for the stack effect to take place, and if designed well, wind-driven and stack-driven ventilation could combine to provide optimal air circulation. Figure 5 below illustrates this; as the wind reaches the left side of the building (high pressure side), cool air is pushed through the interior, shown by the blue arrows. This in turn pushes the warmer interior air out the right side (low pressure side), denoted by the red arrows. At the same time, as the cool air enters through the lower levels of the building, the warm air inside is forced upwards as it is less dense. This air then leaves the building through the openings at the top of the building, denoted by the orange arrows.

Theory and Calculations[edit | edit source]

Although calculations involved in this topic are fairly minimal, the most important factor is volumetric flow rate of air. This helps to determine how much air is being circulated throughout the interior of the building, and with proper knowledge of the variables involved, circulation can be controlled to a minor degree.

Wind-driven ventilation[edit | edit source]

Equation 1 below illustrates how to find the air flow rate for the wind driven ventilation system.

Qwind = K*A*V (1)[11]

where:

- Qwind = Volumetric flow rate of air (m3/h)

- K = Coefficient of effectiveness

- A = Opening cross sectional area (m2)

- V = Outdoor wind speed (m/h)

The coefficient of effectiveness is largely dependent on the angle at which the wind hits the building; for angles of 45 degrees, this figure is generally estimated to be around 0.4, while wind hitting the building at a perpendicular angle would result in a value of around 0.8.[11]

From this equation, it can be concluded that the only controllable factor is the cross sectional area of the opening. This can be adjusted during different months to optimize ventilation. For example, in the summer months where cool, fresh air is desired almost constantly, the area of the opening should be set higher. On the other hand, during the winter months, when the air in the interior is already cool, the opening area should be decreased such that only a necessary amount of ventilation for keeping the air clean and fresh is achieved. Controlling the opening cross sectional area could involve windows or covers.

Stack-driven ventilation[edit | edit source]

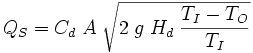

Equation 2 below shows how to calculate the air flow rate in a stack-driven ventilation system.

(2)[3]

where:

- Qs = Stack vent airflow rate (m3/s)

- A = Cross sectional area of opening, assuming inlet and outlet are equal (m2)

- Cd = Discharge coefficient of opening, approximately 0.65

- g = Gravitational constant (9.81 m/s2)

- Hd = Height from midpoint of lower opening to neutral pressure line (m)

- Ti = Interior temperature (K)

- To = Outside temperature (K)

Similarly to wind-driven ventilation, cross sectional area of the openings is the main control factor in the stack-driven ventilation system. The height at which the lower level opening is installed may also be changed by incorporating a sliding cover over a large opening, but this would not make a very significant difference to the flow rate of the air unless the opening was made overly large.

Choosing the Right Location[edit | edit source]

Choosing a location to build a building with natural ventilation is one of the most important factors of all. Different areas of the planet have differing wind speeds and magnitudes, and choosing an area with the appropiate amount would ensure maximum effectiveness.

Obviously, an area with a colder climate may not benefit as much from natural ventilation, as the colder temperatures would result in the interior of the buildings becoming lower than desired. A suitable area would be one with relatively cool summers and nights,[13] and one that sees a fairly large amount of wind activity.

Costs and benefits[edit | edit source]

While different studies conducted have seen different savings, one thing is for certain; natural ventilation will save on energy costs. Figures were gathered from different sources, and although the numbers may not match, every study showed at least a 25% decrease in energy costs for buildings using natural ventilation. Examples of energy savings included 25-33%,[14] 25-50%,[15] and in one case, even 85%[16]!

However, money is not the only thing that is saved. With sustainability in mind, natural ventilation becomes a very attractive option for reducing emissions. Figure 7 below compares the amount of CO2 released into the atmosphere for natural systems vs. mechanical systems.

The list below details the many other savings and benefits that could come about by implementing natural ventilation in a building.

- Less dust

- Less heating required

- Operating costs for mechanical equipment

- Less space occupied by equipment

- Less noise

- Works through power failures[16]

All in all, natural ventilation is a highly recommended solution for saving both money and the environment, provided the location in question is suitable for buildings to implement this technology. To design a versatile system, a combination of wind and stack-driven systems would work best, as mentioned previously; if the air were to become still, the stack effect would still ensure ventilation.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dyer Environmental Controls, "Day Ventilation", http://www.dyerenvironmental.co.uk/day ventilation.gif, Accessed April 3, 2010

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Wind", http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wind, Accessed April 3, 2010

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Wikipedia, "Natural Ventilation", http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_ventilation, Accessed April 3, 2010

- ↑ Massachusetts Institute of Technology, "Stack Vent", http://cmiserver.mit.edu/natvent/Edited Pictures/stack-vent.jpg, Accessed April 5, 2010

- ↑ Wisegeek, "What is the Coandă Effect?", http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-the-coanda-effect.htm, Accessed April 5, 2010

- ↑ Iran Way Tours, http://www.iranwaytours.com/L Wind-Catcher 01.jpg, Accessed April 7, 2010

- ↑ Kinetic Energy Solutions, "Stack Effect", http://www.kinetikenergysolutions.com/solutions/science/stack effect files/stackeffect.gif, Accessed April 7, 2010

- ↑ Bright Hub, "What is the Chimney effect or Stack effect?", http://web.archive.org/web/20120707053819/http://www.brighthub.com:80/engineering/mechanical/articles/29769.aspx, Accessed April 7, 2010

- ↑ EDSL, "Combined wind and stack ventilation", http://www.edsl.net/main/images/combwind.gif, Accessed April 8, 2010

- ↑ Swikipedia, "Natural Ventilation", http://web.archive.org/web/20100602065702/http://www.sustainable-buildings.org:80/wiki/index.php/Natural_ventilation, Accessed April 8, 2010

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Whole Building Design Guide, "Natural Ventilation", http://www.wbdg.org/resources/naturalventilation.php, Accessed April 8, 2010

- ↑ RPS, http://webs.rps205.com/curriculum/ssandvoc/images/EC603F061D5B4D2AA3FC6F950F207E2F.jpg, Accessed April 8, 2010

- ↑ Bob Vila, "Natural Ventilation", http://www.bobvila.com/HowTo_Library/Natural_Ventilation-Ventilation-A1863.html, Accessed April 8, 2010.

- ↑ resource SMART Business, "Natural Ventilation Systems", http://web.archive.org/web/20120324014957/http://www.resourcesmart.vic.gov.au/documents/Natural_Ventilation_Systems.pdf, Accessed April 8, 2010.

- ↑ Building, "Natural ventilation for offices", http://www.building.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=3054640, Accessed April 8, 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Sun North Systems Limited, "Natural Ventilation", http://web.archive.org/web/20100127024149/http://www.sunnorth.com:80/ventilation.htm, Accessed April 8, 2010.

- ↑ Windowmaster, "Natural Ventilation: Fresh air - simple and efficient", http://web.archive.org/web/20061114100224/http://www.windowmaster.com/media/filebank/org/435-0905-UK.pdf, Accessed April 8, 2010