mNo edit summary |

|||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Biochar ready for application.jpg|thumb|Biochar ready for application]] | |||

Biochar | |||

{{Merge to|Biochar}} | |||

Biochar is similar to other charred organic matter, like charcoal. It is developed principally for the remediation of soils, whether in an agricultural setting or for more general rehabilitation of the soil. It can be worked into the soil to increase yields, and its high stability means it can store carbon in the soil for long periods of time. Different production methods lead to different byproducts which can be used as biofuels. | |||

N.B. The field of biochar touches on many different topics, including microbiology, organic chemistry, thermodynamics, agronomy and ecology. It is extremely difficult to have a mastery of any one these fields that is applicable to an emerging topic like biochar, let alone all of them. Therefore, it is greatly appreciated and encouraged that others add to this page according to their expertise. | |||

[[File: | == History == | ||

[[File:Terra Preta.jpg|thumb|A comparison of crop yields in relationship to tropical soils (left) and Terra Preta (right)]] | |||

Biochar is commonly linked to the Terra Preta, or Dark Earths, discovered by Europeans when they arrived in the Amazonian basin. In tropical soils, which are usually nutrient-poor, there were significant swaths that were much darker and more productive than other, lighter soils. It was believed that Amazonian peoples added amendments to the soil in such a way as to greatly enhance its productivity, amendments which were stable for thousands of years. While no way exists to exactly determine the method or rationale behind Terra Preta, some method of charcoal production (via pyrolysis) of organic matter seems to be the linchpin, and improving productivity of the soil the ultimate aim.<ref name="Biochar Farms">Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.</ref> | |||

Since this discovery, biochar has found its way to various corners of the globe. Since the 1800s there has been a growing appreciation for the positive benefits of charcoal soil amendments. Biochar is a recently developed term, indicating pyrolyzed organic matter developed for the sake of introduction into agricultural fields and improvement of depleted soils. Recently, significant energy is being directed towards characterizing biochar, as a variety of feedstocks can be pyrolyzed under a wide array of conditions to achieve a range of purposes. Biochar is not only useful for improving soil productivity, but can also sequester carbon, utilize waste, and produce energy during the pyrolysis process. All these aspects encourage research efforts in both developed and developing countries.<ref name="Lehmann" /> | |||

The leading biochar producing countries and their output are summarized below<ref name="Washington State">Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State. Part 1: Literature Review of Pyrolysis Reactors. First project Report. Department of Biological Systems Engineering and the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and natural Resources, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. 137 pp.</ref>(http://www.ecy.wa.gov/pubs/1107017.pdf): | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! Country | ! Country | ||

! Production | ! Production | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Brazil | | Brazil | ||

| 9.9 million tons/yr | | 9.9 million tons/yr | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Thailand | | Thailand | ||

| 3.9 million tons/yr | | 3.9 million tons/yr | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Ethiopia | | Ethiopia | ||

| 3.2 million tons/yr | | 3.2 million tons/yr | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Tanzania | | Tanzania | ||

| 2.5 million tons/yr | | 2.5 million tons/yr | ||

|- | |- | ||

| India | | India | ||

| 1.7 million tons/yr | | 1.7 million tons/yr | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | | Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||

| 1.7 million tons/yr | | 1.7 million tons/yr | ||

|} | |} | ||

==Scientific/Engineering Theory== | == Scientific/Engineering Theory == | ||

Various aspects of biochar lend it the favorable qualities it possesses. These include chemical properties, nutrient capacities, and microbial interactions. | |||

=== Chemical Properties === | |||

The process of pyrolysis transforms a compound into another by heat alone.<ref name="Hurd">Hurd, Charles Dewitt. The Pyrolysis of Carbon Compounds,. New York: Chemical Catalog, 1929. Print.</ref> Pyrolysis is used to transform a given biomass feedstock (crop waste, dung, wood, etc) into biochar. An array of factors affects this progression, including rate of heating, temperature, heating time, and size of particles.<ref name="Lehmann">Lehmann, Johannes, and Stephen Joseph. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology. London: Earthscan, 2009. Print.</ref>In any organic substance, varying amounts of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon will be found, among other elements. During the process of pyrolysis, elements are released in different proportions. The proportions of different elements are indicative of the stability of the substance. The ratios of hydrogen to carbon (H/C) and oxygen to carbon (O/C), especially, are used to measure the stability of the substance. The decrease in H/C and O/C ratios corresponds to a process known as aromatization, or the formation of aromatic rings. An aromatic compound is significantly more stable. To quantify this, unburned fuel has a rough H/C ratio of 1.5, whereas black carbon is considered to have a ratio of H/C less than or equal to 0.2.<ref name="Lehmann" /> Processed biochar can have a range of H/C values, but those pyrolyzed about 400 C can have H/C ratios below 0.5.<ref name="Lehmann" /> Again, the choice of feedstock can have substantial influence on these ratios. | |||

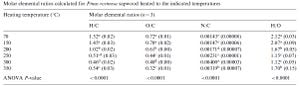

Increasing thermal alteration, due to higher temperatures of pyrolysis, lead to the aromatization of cellulosic compounds.<ref name="Baldock">Baldock JA and Smernik RJ. 2002, 'Chemical composition and bioavailability of thermally altered Pinus resinosa (Red pine) wood', Organic Geochemistry 33: 1093-1109.</ref> This is demonstrated in the following table by decreasing H/C and O/C compounds: | |||

[[File:Baldock table3.jpg|thumb|Baldock JA and Smernik RJ. 2002, 'Chemical composition and bioavailability of thermally altered Pinus resinosa (Red pine) wood', Organic Geochemistry 33: 1093-1109.]] | |||

Aromatic compounds are much more stable than aliphatic compounds, which is why biochar is considered to last for so long in soils. Some biochars are thought to last for thousands of years, e.g., the Terra Preta in the Amazon. Accumulation of organic matter is due in large part to the stability of such soil amendments, leading to higher soil fertility.<ref name="Trompowsky">Trompowsky, P. M., V. d. M. Benites, et al. (2005). "Characterization of humic like substances obtained by chemical oxidation of eucalyptus charcoal." Organic Geochemistry 36(11): 1480-1489.</ref> | |||

</ref> | |||

=== Nutrient Capacities === | |||

A critical aspect of biochar is the effect it has on soil nutrients. | A critical aspect of biochar is the effect it has on soil nutrients. | ||

Biochar supplies nutrients directly to the soil when it is added. | Biochar supplies nutrients directly to the soil when it is added. These are also highly variable and dependent on the feedstock. For example, higher concentrations of phosphorus are found in feed stocks of animal origin. Total nitrogen is also greater for biochars produced from just plants.<ref name="Lehmann" /> However, the nutrients directly supplied by biochar are generally seen as minor in comparison to other benefits.<ref name="Lehmann" /> | ||

It has been demonstrated that biochar increases cation exchange capacity in soils <ref name="Liang"> | It has been demonstrated that biochar increases cation exchange capacity in soils.<ref name="Liang">Liang, B., J. Lehmann, et al. (2006). "Black Carbon Increases Cation Exchange Capacity in Soils." Soil Science Society of America Journal 70(5): 1719-30.</ref>This, in turn, results in a higher retention of nutrients by the biochar, which is made available to plants, increasing yield.<ref name="Major">(Major, J., M. Rondon, et al. (2010). "Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Colombian savanna oxisol." Plant and Soil 333(1-2): 117-128.)</ref>In addition, biochar increases the pH of soils, which has interaction effects with nutrient availability.<ref name="Major" /> Notably, some yields were reported as declining to the increase in pH brought on by biochar application.<ref name="Lehmann" /> Careful attention must be paid to the circumstances of use. | ||

Liang, B., J. Lehmann, et al. (2006). "Black Carbon Increases Cation Exchange Capacity in Soils." Soil Science Society of America Journal 70(5): 1719-30. | |||

</ref> | === Microbial interactions === | ||

(Major, J., M. Rondon, et al. (2010). "Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Colombian savanna oxisol." Plant and Soil 333(1-2): 117-128.) | |||

</ref> | Biochar has many effects on microbial populations. It can provide habitat and protection from predators.<ref name="Lehmann" /> In the Terra Preta soils of the Amazon, compared to surrounding soils, increased microbial biomass is present, along with a lower respiration rate, which indicates higher efficiency.<ref name="Liang" /> Corresponding to this is a lower ratio of CO2 to microbial biomass C, which is considered to be responsible for the longevity of the Terra Preta.<ref name="Lehmann" /> Soil aeration and water holding capacity is influenced by biochar additions, which leads to decreased anaerobic pore space. This in turn limits the possible activity for microbes to participate in the denitrification cycle, and results in decreased N2O emissions.<ref name="Anderson">Anderson, C. R., L. M. Condron, et al. (2011). "Biochar induced soil microbial community change: Implications for biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus." Pedobiologia 54(5-6): 309-320.</ref> Biological nitrogen fixation has also been shown to improve drastically with additions of biochar.<ref name="Rondon">Rondon, M. A., J. Lehmann, et al. (2006). "Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with bio-char additions." Biology and Fertility of Soils 43(6): 699-708.</ref> Numerous other interactions go on with a variety of bacteria and fungi. Inherited microbial communities ought to be considered when introducing biochar. | ||

== Production == | |||

When considering production of biochar, it is essential to know beforehand what is desired. Different products are generated at different operating points. Lower temperature pyrolysis (<400 C) produces higher proportions of solids. Fast pyrolysis, occurring between 400 and 600 C, gives primarily a liquid product, and gasification, occurring above 600 C, gives gaseous products.<ref name="Argyropoulos">Argyropoulos, Dimitris S. Materials, Chemicals, and Energy from Forest Biomass. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 2007. Print.</ref> | |||

Biofuels and synthetic gases are produced during pyrolysis in varying amounts. These synthetic gases, or syn gases, are made up of carbon monoxide, methane and hydrogen gases, and can be used to continue to pyrolization process, after a certain amount of input energy. This input energy needed is about 10-20% of total energy produced by this mechanism. This demonstrates that production of biochar is actually an energy-positive, or exothermic, process. Farmers using this technique can, theoretically, be net producers of energy.<ref>Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web.</ref> | |||

== | === Key factors === | ||

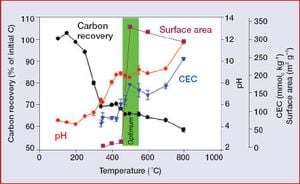

The type of biochar produced also varies widely with temperature. Below is a plot that summarizes the competing considerations that factor into biochar production. | |||

[[File:Optimum table.jpg|thumb|center]] | |||

Several things are important to notice: | Several things are important to notice: | ||

# The rapid and extreme increase in surface area past a certain threshold, approximately 450 C. | # The rapid and extreme increase in surface area past a certain threshold, approximately 450 C. | ||

# The gradual increase (cation exchange capacity and pH) or decline (carbon recovery) of other factors across the range of temperatures. | # The gradual increase (cation exchange capacity and pH) or decline (carbon recovery) of other factors across the range of temperatures. | ||

# The optimum presented here occurs around 450-550 C, to both capture the increase in surface area as well as limit the decline in carbon recovery. | # The optimum presented here occurs around 450-550 C, to both capture the increase in surface area as well as limit the decline in carbon recovery. | ||

Again, choice of factors depends on the ultimate intended purpose of biochar. | Again, choice of factors depends on the ultimate intended purpose of biochar. Greater carbon sequestration occurs with higher carbon recovery, but the biochar will be less stable, due to a limited transition from aliphatic to aromatic carbon. Other benefits will also be limited, such as water-holding capacity and the liming effect for which biochar is often noted. In the conversion to aromatic carbon, mentioned above as increasing with temperature, nutrient availability in the biochar itself also decreases. This occurs alongside increasing cation exchange capacity, which, as was seen earlier, may be responsible for greater availability of nutrients from the soil. | ||

Other factors besides temperature also play a critical role. | Other factors besides temperature also play a critical role. These include heating rate, heating time and particle size. | ||

===Reactor Design Considerations=== | === Reactor Design Considerations === | ||

====Heat Transfer Rate==== | A wide array of reactors are available to process biochar, and can be classified by an array of properties.<ref>Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State. Part 1: Literature Review of Pyrolysis Reactors. First project Report. Department of Biological Systems Engineering and the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and natural Resources, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. 137 pp.</ref> | ||

Slow pyrolysis occurs at a rate of 5-7 C/min, and produces less liquid and more char. | |||

Bridgwater, A. (2007) 'IEA Bioenergy Update 27: Biomass Pyrolysis', Biomass and Bioenergy, vol 31, ppI-V | ==== Heat Transfer Rate ==== | ||

</ref> | |||

Slow pyrolysis occurs at a rate of 5-7 C/min, and produces less liquid and more char. Fast pyrolysis incorporates heating rates above 300 C/min and generates primarily bio-oil. The following table summarizes production of different phases under different conditions.<ref name="Bridgwater">Bridgwater, A. (2007) 'IEA Bioenergy Update 27: Biomass Pyrolysis', Biomass and Bioenergy, vol 31, ppI-V</ref> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! Mode | ! Mode | ||

! Conditions | ! Conditions | ||

| Line 118: | Line 100: | ||

| Fast | | Fast | ||

| Moderate temperature, around 500 C, short hot vapor residence time ~ 1 second | | Moderate temperature, around 500 C, short hot vapor residence time ~ 1 second | ||

| | | 75% | ||

| 2% | | 2% | ||

| 13% | | 13% | ||

| Line 141: | Line 123: | ||

|} | |} | ||

====Mode of Operation==== | ==== Mode of Operation ==== | ||

Batch, semi-batch and continuous methods can be utilized. | Batch, semi-batch and continuous methods can be utilized. | ||

Batch methods are primarily for generating biochar, so byproducts like bio-oil and gases are not utilized and often vented, leading to significant pollution. | Batch methods are primarily for generating biochar, so byproducts like bio-oil and gases are not utilized and often vented, leading to significant pollution. Since it must go through a repetitive cycle of warming up and cooling down, much energy is expended in this method. | ||

Semi-batch setups transfer heat among batch reactors, leading to lower energy expenditures. | Semi-batch setups transfer heat among batch reactors, leading to lower energy expenditures. Liquid may be recovered, but biochar is the primary desired product. | ||

Continuous reactors are more efficient than either batch or semi-batch, but have their own limitations. | Continuous reactors are more efficient than either batch or semi-batch, but have their own limitations. Technical expertise, flow rate of feedstock, and capital investment are all significant. | ||

==== Heating Methods ==== | |||

Heating may occur via partial combustion, carbonization via inert gases, or indirect heating. | Heating may occur via partial combustion, carbonization via inert gases, or indirect heating. | ||

Partial combustion is generally the mode utilized for small-scale reactors. | Partial combustion is generally the mode utilized for small-scale reactors. A portion of the raw material is combusted, which generates the energy needed for the process to continue. | ||

Inert gases can be heated up outside the reactor with another fuel source, and brought into contact with the feedstock. | Inert gases can be heated up outside the reactor with another fuel source, and brought into contact with the feedstock. This leads to carbonization into biochar, and produces high yields. | ||

The reactor can also be heated from the outside, with the feedstock kept in an anoxic environment. | The reactor can also be heated from the outside, with the feedstock kept in an anoxic environment. With the beginning of pyrolysis, gases produced can generate energy to continue the process. Byproducts can be recovered more easily, and yields are high. | ||

==== Other factors ==== | |||

Numerous other factors come into play in reactor design, including: | Numerous other factors come into play in reactor design, including: | ||

| Line 167: | Line 152: | ||

* Pretreatment | * Pretreatment | ||

These are further discussed in "Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State<ref> | These are further discussed in "Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State".<ref>Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State. Part 1: Literature Review of Pyrolysis Reactors. First project Report. Department of Biological Systems Engineering and the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and natural Resources, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. 137 pp.</ref> However, for application in developing countries, it may be best to briefly describe a few particular designs. | ||

Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. | |||

</ref> | === Production Options === | ||

However, for application in developing countries, it may be best to briefly describe a few particular designs. | |||

==== Pit and Mound Kilns ==== | |||

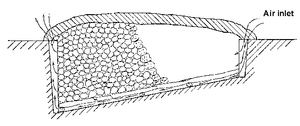

[[File:BiocharTech FAO PitKiln AMSW.png|thumb]] | |||

Pit and mound kilns are the simplest types of kilns. In a pit kiln, a small fire is started inside a pit and additional wood is added. Leaves and branches are piled on top to make a sort of shelf for dirt to be added on top. It must be continually managed to allow the proper inflow of air. A mound kiln follows a similar type of operation, only pyrolysis takes place above ground, and air inlets provide more regular means of regulating air flow. Both of these kilns have limited yield of biochar and contribute greatly to air pollution. | |||

==== Brick Kiln ==== | |||

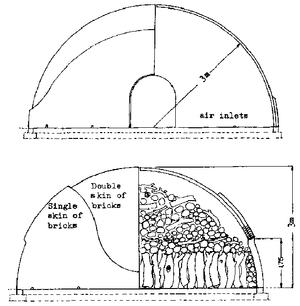

[[File:BiocharTech FAO BrickKiln AMSW.png|thumb]] | |||

A brick kiln can be utilized to make biochar as well. This is a simple batch reactor with a brick outer layer, with air filtration, and two doors for loading and unloading char. | |||

==== Metal Kiln ==== | |||

[[File:BiocharTech FAO MetalKiln AMSW.jpg|thumb]] | |||

An example of a metal kiln is that produced by Tropical Products Institute (TPI). A cylindrical body is covered by a conical section. This cover has steam release ports, and the body has air inlets around the bottom. This design allows air to be much more easily controlled than the mud or brick kilns, and tends to produce more biochar of greater quality. Unfortunately, this design still produces significant amounts of air pollution. | |||

==== | ==== Concrete Kiln ==== | ||

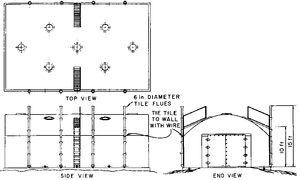

[[File:BiocharTech FAO MissouriKiln AMSW.png|thumb]] | |||

[[File: | |||

This is a rectangular structure made of concrete with steel doors. It is also known as the Missouri kiln. It can produce about 3 times the amount of biochar as a brick kiln, but at a better quality. While technically complex, this kiln has several advantages. Thermocouples allow temperature monitoring, which facilitates air flow control. Chimneys can be augmented with a flue and afterburner to limit atmospheric emissions.<ref name="Lehmann" /> | |||

==== | ==== Yields ==== | ||

The following table summarizes potential charcoal yield from these kilns.<ref name="Kammen">Kammen, D. M. and Lew, D. J. (2005) Review of Technologies for the Production and Use of Charcoal, Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory, Berkeley University, 1 Mar. 2005. Web. 22 Apr. 2012. http://web.archive.org/web/20110913105616/http://rael.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/very-old-site/Kammen.charcoal.pdf</ref> | |||

The following table summarizes potential charcoal yield from these kilns<ref name = "Kammen"> | |||

Kammen, D. M. and Lew, D. J. (2005) Review of Technologies for the Production and Use of Charcoal, Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory, Berkeley University, 1 Mar. 2005. Web. 22 Apr. 2012. | |||

</ref> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! Kiln Type | ! Kiln Type | ||

! Charcoal yield (%) | ! Charcoal yield (%) | ||

| Line 218: | Line 206: | ||

Many other, more complex kiln designs exist, but these are likely outside the scope of resources for smallholder farmers who would benefit most from biochar applications. | Many other, more complex kiln designs exist, but these are likely outside the scope of resources for smallholder farmers who would benefit most from biochar applications. | ||

==Impacts== | == Impacts == | ||

Biochar, as mentioned above, has some important features that have led to its popularity. | |||

Biochar, as mentioned above, has some important features that have led to its popularity. These include: | |||

* Sequestration of carbon | * Sequestration of carbon | ||

| Line 226: | Line 215: | ||

* Soil improvement | * Soil improvement | ||

===Sequestration of Carbon=== | === Sequestration of Carbon === | ||

During the pyrolysis process, carbon structures are converted from aliphatic to aromatic form. | |||

During the pyrolysis process, carbon structures are converted from aliphatic to aromatic form. This aromaticity leads to high stability in soil. Thus, if organic material, such as crop waste, dung, or wood is pyrolyzed and worked into the soil, the carbon present in these materials will stay in the soil for a significant period, perhaps on the order of thousands of years. It is projected that substantial amounts of carbon can be sequestered in soil.<ref name="Lehmann" /> | |||

A couple constraints must be met in order for this to work. The rate at which carbon in plants is converted into biochar must match the rate at which plants are grown. Additionally, the rate of decomposition of biochar must be slower than that of plants.<ref name="Lehmann" /> This is dependent, as discussed previously, on the transition from aliphatic to aromatic carbon. Variations in biochar production and application affect potential sequestration scales, but Johannes Lehmann of Cornell University has estimated that cropland could store 224 gigatons of carbon (GtC), and temperate grasslands could sequester 175 GtC. This is an amount roughly equivalent to all biomass on earth.<ref name="Bates">Bates, Albert K. The Biochar Solution: Carbon Farming and Climate Change. Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society, 2010. Print.</ref> About a quarter of this total amount could be secured by two changes in practice. One is switching from slash and burn to slash and char, where felled trees are turned into biochar and turned into the soil, instead of simply burned. A second is diverting wastes into biochar. | |||

=== Waste Removal === | |||

Organic waste generation is a growing concern. Waste generated by human and animal populations must be dealt with in a productive manner. Unfortunately, these wastes often pollute surface and groundwater resources. Biochar offers a solution to this, as organic wastes can be used as feedstocks. Waste removal limits effects on climate change in several ways: | |||

* Decrease in methane emissions from waste decomposition | * Decrease in methane emissions from waste decomposition | ||

* Decrease in energy use for recycling and transport of waste | * Decrease in energy use for recycling and transport of waste | ||

* Recovery of energy <ref name=Lehmann /> <ref name = "Ackerman">Ackerman, F. (2000) 'Waste management and climate change', Local Environment, vol 5, pp223-229.</ref> | * Recovery of energy<ref name="Lehmann" /><ref name="Ackerman">Ackerman, F. (2000) 'Waste management and climate change', Local Environment, vol 5, pp223-229.</ref> | ||

=== Energy generation === | |||

As discussed above, the pyrolysis process can be used to generate energy, in addition to biochar. However, over the range of production operating temperatures, there is a trade-off between the amount of biochar produced and energy produced. It is likely that truly significant amounts of energy can be generated, to the point that biochar production may represent a source of alternative energy, though far from sufficient on its own.<ref name="Lehmann" /> Pyrolysis can offer a cleaner alternative to simple biomass burning, as well, presenting a potential solution to the problem of indoor air quality in many developing countries. | |||

As discussed above, the pyrolysis process can be used to generate energy, in addition to biochar. | |||

===Soil improvement=== | === Soil improvement === | ||

Finally, there is the role that biochar can play in improving soil. This can happen by direct application of nutrients found in biochar, but also indirectly. Such benefits can be harnessed for greater agricultural productivity and more general soil rehabilitation of degraded or desertified terrain. | |||

During production, gases in organic material is burned off, leaving behind mostly carbon with a great deal of pore space and surface area <ref> | The current state of agriculture is far from sustainable. Heavy emphasis on monocultures leads to the mining of soil nutrients. Excessive use of inorganic fertilizers run the risk of acidifying soil, in addition to extreme levels of surface runoff that pollute waters downstream, creating dead zones. Biochar alone will not solve these problems, but is an important component of a shift in direction. | ||

Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web. 22 Apr. 2012. | |||

</ref> | During production, gases in organic material is burned off, leaving behind mostly carbon with a great deal of pore space and surface area.<ref>Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.</ref>As discussed above, these qualities enhance water holding capacity and cation exchange capacity, which in turn increase the availability of soil nutrients to plants. This gives longevity to the soil, and reduces the need for fertilizer use. Biochar can also increase the efficiency of soil biota. In addition, biochar gives a liming effect to the soil by raising pH, and increasing nutrient availability to plants. | ||

The actual effects of biochar on soil are, as has been mentioned numerous times in this article, dependent on several factors: | The actual effects of biochar on soil are, as has been mentioned numerous times in this article, dependent on several factors: | ||

* Feedstock used | * Feedstock used | ||

* Application rate and combination with fertilizers | * Application rate and combination with fertilizers | ||

| Line 258: | Line 249: | ||

* Crops grown | * Crops grown | ||

Thus, it is nearly impossible, at this point, to *predict* the effects of biochar on soils. | Thus, it is nearly impossible, at this point, to *predict* the effects of biochar on soils. Characterization of biochar remains an incredibly important task for the purposes of defining relevant properties and enabling communication about various types. Feedstock properties that are important to consider include:<ref name="Lehmann" /> | ||

* Proportion of organic components, including lignin, cellulose, and others | * Proportion of organic components, including lignin, cellulose, and others | ||

* Proportion of inorganic compounds | * Proportion of inorganic compounds | ||

| Line 267: | Line 259: | ||

* Moisture content | * Moisture content | ||

Of these, to simplify classification, four parameters have been proposed:<ref name=Lehmann/> | Of these, to simplify classification, four parameters have been proposed:<ref name="Lehmann" /> | ||

* Contents of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and labile and stable fraction of total C | * Contents of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and labile and stable fraction of total C | ||

* Composition by other elements | * Composition by other elements | ||

| Line 275: | Line 268: | ||

Parameters of biochar production, enumerated briefly above, need to also be recorded and documented. | Parameters of biochar production, enumerated briefly above, need to also be recorded and documented. | ||

==Evaluation== | == Evaluation == | ||

Due to the wide variety of conditions that lead to biochar production, numerous effects, both positive and negative, have been reported. | Due to the wide variety of conditions that lead to biochar production, numerous effects, both positive and negative, have been reported. | ||

Effects for agriculture are primarily in terms of improved yield. | Effects for agriculture are primarily in terms of improved yield. Measures of soil nutrients, water-holding capacity and pH are also important. | ||

Numerous tests have been conducted with biochar, and the effects on crop yields have been recorded. | Numerous tests have been conducted with biochar, and the effects on crop yields have been recorded. Some reasons given for improvements are:<ref name="Lehmann" /> | ||

* Water-holding capacity | * Water-holding capacity | ||

* Black color on temperature | * Black color on temperature | ||

| Line 290: | Line 285: | ||

Some reasons for yield reductions are: | Some reasons for yield reductions are: | ||

* pH-induced micro-nutrient deficiency | * pH-induced micro-nutrient deficiency | ||

* Change in soil properties | * Change in soil properties | ||

A range of responses has been recorded for different parameters. | A range of responses has been recorded for different parameters. Biomass, yield, tree density, height and volume are all potential descriptors of biochar response, but yield is likely the most widely applicable. A range of responses in yield are known, from a reduction of 71% to an increase of as much as 880%.<ref name="Lehmann" /> | ||

Another review of crop responses to biochar applications found the following results:<ref name="Jeffery">Jeffery, S., F. G. A. Verheijen, et al. (2011). "A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application to soils on crop productivity using meta-analysis." Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 144(1): 175-187.</ref> | |||

* An average increase of 10% on crop production, with a range from 55% decrease to 65% increase in crop productivity | * An average increase of 10% on crop production, with a range from 55% decrease to 65% increase in crop productivity | ||

* Modest improvements for acidic and neutral soils (14% and 13%, respectively) | * Modest improvements for acidic and neutral soils (14% and 13%, respectively) | ||

* Similar improvements for coarse and medium texture soils (10% and 13%, respectively) | * Similar improvements for coarse and medium texture soils (10% and 13%, respectively) | ||

The wide range of operating conditions and data recorded in the tests reviewed point to the need for recording and communicating the maximum amount of information possible. | The wide range of operating conditions and data recorded in the tests reviewed point to the need for recording and communicating the maximum amount of information possible. This will help researchers analyze the effect of various details. | ||

== Recommendations == | |||

Given biochar's tremendous potential to alleviate climate change, increase agricultural productivity, utilize waste effectively, and generate energy, it is essential to learn as much about it and the best ways to use it as possible. Some steps to encourage this include: | |||

* Developing a universal classification system of biochars | * Developing a universal classification system of biochars | ||

* Developing a standard set of data to collect during biochar tests | * Developing a standard set of data to collect during biochar tests | ||

| Line 312: | Line 309: | ||

* Evaluating which crops respond best to different biochar applications, to make these results as relevant as possible for small-scale farmers | * Evaluating which crops respond best to different biochar applications, to make these results as relevant as possible for small-scale farmers | ||

== Dissemination == | |||

Numerous groups are promoting and supporting the use of biochar. Some of these include: | Numerous groups are promoting and supporting the use of biochar. Some of these include: | ||

* International Biochar Initiative (IBI) - The leading source of information on biochar, IBI disseminates biochar information, in addition to developing sustainability guidelines and monitoring biochar projects. [http://www.biochar-international.org] | * International Biochar Initiative (IBI) - The leading source of information on biochar, IBI disseminates biochar information, in addition to developing sustainability guidelines and monitoring biochar projects. [http://www.biochar-international.org] | ||

* Biochar Farms - The mission of Biochar Farms is to gather and share reliable information about biochar. [http://www.biocharfarms.org] | * Biochar Farms - The mission of Biochar Farms is to gather and share reliable information about biochar. [http://www.biocharfarms.org] | ||

* Biochar Discussion List - This website has a host of discussions about various aspects about biochar - producing and purchasing biochar, on-going research, etc. [http://terrapreta.bioenergylists.org/] | * Biochar Discussion List - This website has a host of discussions about various aspects about biochar - producing and purchasing biochar, on-going research, etc. [http://terrapreta.bioenergylists.org/] | ||

==References== | == References == | ||

<references/> | |||

<references /> | |||

* Brewer, C. E., R. Unger, et al. (2011). "Criteria to Select Biochars for Field Studies based on Biochar Chemical Properties." BioEnergy Research 4(4): 312-323. | * Brewer, C. E., R. Unger, et al. (2011). "Criteria to Select Biochars for Field Studies based on Biochar Chemical Properties." BioEnergy Research 4(4): 312-323. | ||

* Bruun, E. W., H. Hauggaard-Nielsen, et al. (2011). "Influence of fast pyrolysis temperature on biochar labile fraction and short-term carbon loss in a loamy soil." Biomass and Bioenergy 35(3): 1182-1189. | * Bruun, E. W., H. Hauggaard-Nielsen, et al. (2011). "Influence of fast pyrolysis temperature on biochar labile fraction and short-term carbon loss in a loamy soil." Biomass and Bioenergy 35(3): 1182-1189. | ||

* Demirbas, A. (2004). "Effects of temperature and particle size on bio-char yield from pyrolysis of agricultural residues." Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 72(2): 243-248. | * Demirbas, A. (2004). "Effects of temperature and particle size on bio-char yield from pyrolysis of agricultural residues." Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 72(2): 243-248. | ||

* Demirbas, A. (2007). "Bio-fuels from Agricutural Residues." Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 30(2): 101-109. | * Demirbas, A. (2007). "Bio-fuels from Agricutural Residues." Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 30(2): 101-109. | ||

* Duku, M. H., S. Gu, et al. (2011). "Biochar production potential in Ghana—A review." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15(8): 3539-3551. | * Duku, M. H., S. Gu, et al. (2011). "Biochar production potential in Ghana—A review." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15(8): 3539-3551. | ||

* Kammann, C. I., S. Linsel, et al. (2011). "Influence of biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa Willd and on soil–plant relations." Plant and Soil 345(1-2): 195-210. | * Kammann, C. I., S. Linsel, et al. (2011). "Influence of biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa Willd and on soil–plant relations." Plant and Soil 345(1-2): 195-210. | ||

* Karhu, K., T. Mattila, et al. (2011). "Biochar addition to agricultural soil increased CH4 uptake and water holding capacity – Results from a short-term pilot field study." Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 140(1-2): 309-313. | * Karhu, K., T. Mattila, et al. (2011). "Biochar addition to agricultural soil increased CH4 uptake and water holding capacity – Results from a short-term pilot field study." Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 140(1-2): 309-313. | ||

* Koide, R. T., K. Petprakob, et al. (2011). "Quantitative analysis of biochar in field soil." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43(7): 1563-1568. | * Koide, R. T., K. Petprakob, et al. (2011). "Quantitative analysis of biochar in field soil." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43(7): 1563-1568. | ||

* Lehmann, J., J. Gaunt, et al. (2006). "Bio-char Sequestration in Terrestrial Ecosystems – A Review." Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 11(2): 395-419. | * Lehmann, J., J. Gaunt, et al. (2006). "Bio-char Sequestration in Terrestrial Ecosystems – A Review." Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 11(2): 395-419. | ||

* Li, D., W. C. Hockaday, et al. (2011). "Earthworm avoidance of biochar can be mitigated by wetting." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43(8): 1732-1737. | * Li, D., W. C. Hockaday, et al. (2011). "Earthworm avoidance of biochar can be mitigated by wetting." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43(8): 1732-1737. | ||

* Noguera, D., M. Rondón, et al. (2010). "Contrasted effect of biochar and earthworms on rice growth and resource allocation in different soils." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42(7): 1017-1027. | * Noguera, D., M. Rondón, et al. (2010). "Contrasted effect of biochar and earthworms on rice growth and resource allocation in different soils." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42(7): 1017-1027. | ||

* Smith, J. L., H. P. Collins, et al. (2010). "The effect of young biochar on soil respiration." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42(12): 2345-2347. | * Smith, J. L., H. P. Collins, et al. (2010). "The effect of young biochar on soil respiration." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42(12): 2345-2347. | ||

* Song, W. and M. Guo (2011). "Quality variations of poultry litter biochar generated at different pyrolysis temperatures." Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. | * Song, W. and M. Guo (2011). "Quality variations of poultry litter biochar generated at different pyrolysis temperatures." Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. | ||

* Steinbeiss, S., G. Gleixner, et al. (2009). "Effect of biochar amendment on soil carbon balance and soil microbial activity." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41(6): 1301-1310. | * Steinbeiss, S., G. Gleixner, et al. (2009). "Effect of biochar amendment on soil carbon balance and soil microbial activity." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41(6): 1301-1310. | ||

* Uzoma, K. C., M. Inoue, et al. (2011). "Effect of cow manure biochar on maize productivity under sandy soil condition." Soil Use and Management 27(2): 205-212. | * Uzoma, K. C., M. Inoue, et al. (2011). "Effect of cow manure biochar on maize productivity under sandy soil condition." Soil Use and Management 27(2): 205-212. | ||

* Van Zwieten, L., S. Kimber, et al. (2009). "Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility." Plant and Soil 327(1-2): 235-246. | * Van Zwieten, L., S. Kimber, et al. (2009). "Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility." Plant and Soil 327(1-2): 235-246. | ||

* Warnock, D. D., J. Lehmann, et al. (2007). "Mycorrhizal responses to biochar in soil – concepts and mechanisms." Plant and Soil 300(1-2): 9-20. | * Warnock, D. D., J. Lehmann, et al. (2007). "Mycorrhizal responses to biochar in soil – concepts and mechanisms." Plant and Soil 300(1-2): 9-20. | ||

{{Page data}} | |||

[[Category:Biochar]] | [[Category:Biochar]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:24, 29 June 2023

Biochar is similar to other charred organic matter, like charcoal. It is developed principally for the remediation of soils, whether in an agricultural setting or for more general rehabilitation of the soil. It can be worked into the soil to increase yields, and its high stability means it can store carbon in the soil for long periods of time. Different production methods lead to different byproducts which can be used as biofuels.

N.B. The field of biochar touches on many different topics, including microbiology, organic chemistry, thermodynamics, agronomy and ecology. It is extremely difficult to have a mastery of any one these fields that is applicable to an emerging topic like biochar, let alone all of them. Therefore, it is greatly appreciated and encouraged that others add to this page according to their expertise.

History[edit | edit source]

Biochar is commonly linked to the Terra Preta, or Dark Earths, discovered by Europeans when they arrived in the Amazonian basin. In tropical soils, which are usually nutrient-poor, there were significant swaths that were much darker and more productive than other, lighter soils. It was believed that Amazonian peoples added amendments to the soil in such a way as to greatly enhance its productivity, amendments which were stable for thousands of years. While no way exists to exactly determine the method or rationale behind Terra Preta, some method of charcoal production (via pyrolysis) of organic matter seems to be the linchpin, and improving productivity of the soil the ultimate aim.[1]

Since this discovery, biochar has found its way to various corners of the globe. Since the 1800s there has been a growing appreciation for the positive benefits of charcoal soil amendments. Biochar is a recently developed term, indicating pyrolyzed organic matter developed for the sake of introduction into agricultural fields and improvement of depleted soils. Recently, significant energy is being directed towards characterizing biochar, as a variety of feedstocks can be pyrolyzed under a wide array of conditions to achieve a range of purposes. Biochar is not only useful for improving soil productivity, but can also sequester carbon, utilize waste, and produce energy during the pyrolysis process. All these aspects encourage research efforts in both developed and developing countries.[2] The leading biochar producing countries and their output are summarized below[3](http://www.ecy.wa.gov/pubs/1107017.pdf):

| Country | Production |

|---|---|

| Brazil | 9.9 million tons/yr |

| Thailand | 3.9 million tons/yr |

| Ethiopia | 3.2 million tons/yr |

| Tanzania | 2.5 million tons/yr |

| India | 1.7 million tons/yr |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1.7 million tons/yr |

Scientific/Engineering Theory[edit | edit source]

Various aspects of biochar lend it the favorable qualities it possesses. These include chemical properties, nutrient capacities, and microbial interactions.

Chemical Properties[edit | edit source]

The process of pyrolysis transforms a compound into another by heat alone.[4] Pyrolysis is used to transform a given biomass feedstock (crop waste, dung, wood, etc) into biochar. An array of factors affects this progression, including rate of heating, temperature, heating time, and size of particles.[2]In any organic substance, varying amounts of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon will be found, among other elements. During the process of pyrolysis, elements are released in different proportions. The proportions of different elements are indicative of the stability of the substance. The ratios of hydrogen to carbon (H/C) and oxygen to carbon (O/C), especially, are used to measure the stability of the substance. The decrease in H/C and O/C ratios corresponds to a process known as aromatization, or the formation of aromatic rings. An aromatic compound is significantly more stable. To quantify this, unburned fuel has a rough H/C ratio of 1.5, whereas black carbon is considered to have a ratio of H/C less than or equal to 0.2.[2] Processed biochar can have a range of H/C values, but those pyrolyzed about 400 C can have H/C ratios below 0.5.[2] Again, the choice of feedstock can have substantial influence on these ratios. Increasing thermal alteration, due to higher temperatures of pyrolysis, lead to the aromatization of cellulosic compounds.[5] This is demonstrated in the following table by decreasing H/C and O/C compounds:

Aromatic compounds are much more stable than aliphatic compounds, which is why biochar is considered to last for so long in soils. Some biochars are thought to last for thousands of years, e.g., the Terra Preta in the Amazon. Accumulation of organic matter is due in large part to the stability of such soil amendments, leading to higher soil fertility.[6]

Nutrient Capacities[edit | edit source]

A critical aspect of biochar is the effect it has on soil nutrients. Biochar supplies nutrients directly to the soil when it is added. These are also highly variable and dependent on the feedstock. For example, higher concentrations of phosphorus are found in feed stocks of animal origin. Total nitrogen is also greater for biochars produced from just plants.[2] However, the nutrients directly supplied by biochar are generally seen as minor in comparison to other benefits.[2] It has been demonstrated that biochar increases cation exchange capacity in soils.[7]This, in turn, results in a higher retention of nutrients by the biochar, which is made available to plants, increasing yield.[8]In addition, biochar increases the pH of soils, which has interaction effects with nutrient availability.[8] Notably, some yields were reported as declining to the increase in pH brought on by biochar application.[2] Careful attention must be paid to the circumstances of use.

Microbial interactions[edit | edit source]

Biochar has many effects on microbial populations. It can provide habitat and protection from predators.[2] In the Terra Preta soils of the Amazon, compared to surrounding soils, increased microbial biomass is present, along with a lower respiration rate, which indicates higher efficiency.[7] Corresponding to this is a lower ratio of CO2 to microbial biomass C, which is considered to be responsible for the longevity of the Terra Preta.[2] Soil aeration and water holding capacity is influenced by biochar additions, which leads to decreased anaerobic pore space. This in turn limits the possible activity for microbes to participate in the denitrification cycle, and results in decreased N2O emissions.[9] Biological nitrogen fixation has also been shown to improve drastically with additions of biochar.[10] Numerous other interactions go on with a variety of bacteria and fungi. Inherited microbial communities ought to be considered when introducing biochar.

Production[edit | edit source]

When considering production of biochar, it is essential to know beforehand what is desired. Different products are generated at different operating points. Lower temperature pyrolysis (<400 C) produces higher proportions of solids. Fast pyrolysis, occurring between 400 and 600 C, gives primarily a liquid product, and gasification, occurring above 600 C, gives gaseous products.[11]

Biofuels and synthetic gases are produced during pyrolysis in varying amounts. These synthetic gases, or syn gases, are made up of carbon monoxide, methane and hydrogen gases, and can be used to continue to pyrolization process, after a certain amount of input energy. This input energy needed is about 10-20% of total energy produced by this mechanism. This demonstrates that production of biochar is actually an energy-positive, or exothermic, process. Farmers using this technique can, theoretically, be net producers of energy.[12]

Key factors[edit | edit source]

The type of biochar produced also varies widely with temperature. Below is a plot that summarizes the competing considerations that factor into biochar production.

Several things are important to notice:

- The rapid and extreme increase in surface area past a certain threshold, approximately 450 C.

- The gradual increase (cation exchange capacity and pH) or decline (carbon recovery) of other factors across the range of temperatures.

- The optimum presented here occurs around 450-550 C, to both capture the increase in surface area as well as limit the decline in carbon recovery.

Again, choice of factors depends on the ultimate intended purpose of biochar. Greater carbon sequestration occurs with higher carbon recovery, but the biochar will be less stable, due to a limited transition from aliphatic to aromatic carbon. Other benefits will also be limited, such as water-holding capacity and the liming effect for which biochar is often noted. In the conversion to aromatic carbon, mentioned above as increasing with temperature, nutrient availability in the biochar itself also decreases. This occurs alongside increasing cation exchange capacity, which, as was seen earlier, may be responsible for greater availability of nutrients from the soil. Other factors besides temperature also play a critical role. These include heating rate, heating time and particle size.

Reactor Design Considerations[edit | edit source]

A wide array of reactors are available to process biochar, and can be classified by an array of properties.[13]

Heat Transfer Rate[edit | edit source]

Slow pyrolysis occurs at a rate of 5-7 C/min, and produces less liquid and more char. Fast pyrolysis incorporates heating rates above 300 C/min and generates primarily bio-oil. The following table summarizes production of different phases under different conditions.[14]

| Mode | Conditions | Liquid | Solid | Gas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | Moderate temperature, around 500 C, short hot vapor residence time ~ 1 second | 75% | 2% | 13% |

| Intermediate | Moderate temperature, around 500 C, moderate hot vapor residence time ~ 10-20 seconds | 0% | 20% | 30% |

| Slow | Low temperature, around 400 C, very long solids residence time | 30% | 35% | 35% |

| Gasification | High temperature, around 800 C, long vapour residence time | 5% | 10% | 85% |

Mode of Operation[edit | edit source]

Batch, semi-batch and continuous methods can be utilized. Batch methods are primarily for generating biochar, so byproducts like bio-oil and gases are not utilized and often vented, leading to significant pollution. Since it must go through a repetitive cycle of warming up and cooling down, much energy is expended in this method. Semi-batch setups transfer heat among batch reactors, leading to lower energy expenditures. Liquid may be recovered, but biochar is the primary desired product. Continuous reactors are more efficient than either batch or semi-batch, but have their own limitations. Technical expertise, flow rate of feedstock, and capital investment are all significant.

Heating Methods[edit | edit source]

Heating may occur via partial combustion, carbonization via inert gases, or indirect heating. Partial combustion is generally the mode utilized for small-scale reactors. A portion of the raw material is combusted, which generates the energy needed for the process to continue. Inert gases can be heated up outside the reactor with another fuel source, and brought into contact with the feedstock. This leads to carbonization into biochar, and produces high yields. The reactor can also be heated from the outside, with the feedstock kept in an anoxic environment. With the beginning of pyrolysis, gases produced can generate energy to continue the process. Byproducts can be recovered more easily, and yields are high.

Other factors[edit | edit source]

Numerous other factors come into play in reactor design, including:

- Construction Materials

- Portability

- Reactor Position

- Raw Materials

- Mechanisms of Loading and Unloading

- Size of Kiln

- Ignition of Feedstock

- Process Control

- Pressure

- Pretreatment

These are further discussed in "Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State".[15] However, for application in developing countries, it may be best to briefly describe a few particular designs.

Production Options[edit | edit source]

Pit and Mound Kilns[edit | edit source]

Pit and mound kilns are the simplest types of kilns. In a pit kiln, a small fire is started inside a pit and additional wood is added. Leaves and branches are piled on top to make a sort of shelf for dirt to be added on top. It must be continually managed to allow the proper inflow of air. A mound kiln follows a similar type of operation, only pyrolysis takes place above ground, and air inlets provide more regular means of regulating air flow. Both of these kilns have limited yield of biochar and contribute greatly to air pollution.

Brick Kiln[edit | edit source]

A brick kiln can be utilized to make biochar as well. This is a simple batch reactor with a brick outer layer, with air filtration, and two doors for loading and unloading char.

Metal Kiln[edit | edit source]

An example of a metal kiln is that produced by Tropical Products Institute (TPI). A cylindrical body is covered by a conical section. This cover has steam release ports, and the body has air inlets around the bottom. This design allows air to be much more easily controlled than the mud or brick kilns, and tends to produce more biochar of greater quality. Unfortunately, this design still produces significant amounts of air pollution.

Concrete Kiln[edit | edit source]

This is a rectangular structure made of concrete with steel doors. It is also known as the Missouri kiln. It can produce about 3 times the amount of biochar as a brick kiln, but at a better quality. While technically complex, this kiln has several advantages. Thermocouples allow temperature monitoring, which facilitates air flow control. Chimneys can be augmented with a flue and afterburner to limit atmospheric emissions.[2]

Yields[edit | edit source]

The following table summarizes potential charcoal yield from these kilns.[16]

| Kiln Type | Charcoal yield (%) |

|---|---|

| Pit | 12.5-30 |

| Mound | 2-42 |

| Brick | 12.5-33 |

| Portable Steel (TPI) | 18.9-31.4 |

| Concrete (Missouri) | 33 |

Many other, more complex kiln designs exist, but these are likely outside the scope of resources for smallholder farmers who would benefit most from biochar applications.

Impacts[edit | edit source]

Biochar, as mentioned above, has some important features that have led to its popularity. These include:

- Sequestration of carbon

- Utilization of organic waste

- Energy generation

- Soil improvement

Sequestration of Carbon[edit | edit source]

During the pyrolysis process, carbon structures are converted from aliphatic to aromatic form. This aromaticity leads to high stability in soil. Thus, if organic material, such as crop waste, dung, or wood is pyrolyzed and worked into the soil, the carbon present in these materials will stay in the soil for a significant period, perhaps on the order of thousands of years. It is projected that substantial amounts of carbon can be sequestered in soil.[2]

A couple constraints must be met in order for this to work. The rate at which carbon in plants is converted into biochar must match the rate at which plants are grown. Additionally, the rate of decomposition of biochar must be slower than that of plants.[2] This is dependent, as discussed previously, on the transition from aliphatic to aromatic carbon. Variations in biochar production and application affect potential sequestration scales, but Johannes Lehmann of Cornell University has estimated that cropland could store 224 gigatons of carbon (GtC), and temperate grasslands could sequester 175 GtC. This is an amount roughly equivalent to all biomass on earth.[17] About a quarter of this total amount could be secured by two changes in practice. One is switching from slash and burn to slash and char, where felled trees are turned into biochar and turned into the soil, instead of simply burned. A second is diverting wastes into biochar.

Waste Removal[edit | edit source]

Organic waste generation is a growing concern. Waste generated by human and animal populations must be dealt with in a productive manner. Unfortunately, these wastes often pollute surface and groundwater resources. Biochar offers a solution to this, as organic wastes can be used as feedstocks. Waste removal limits effects on climate change in several ways:

- Decrease in methane emissions from waste decomposition

- Decrease in energy use for recycling and transport of waste

- Recovery of energy[2][18]

Energy generation[edit | edit source]

As discussed above, the pyrolysis process can be used to generate energy, in addition to biochar. However, over the range of production operating temperatures, there is a trade-off between the amount of biochar produced and energy produced. It is likely that truly significant amounts of energy can be generated, to the point that biochar production may represent a source of alternative energy, though far from sufficient on its own.[2] Pyrolysis can offer a cleaner alternative to simple biomass burning, as well, presenting a potential solution to the problem of indoor air quality in many developing countries.

Soil improvement[edit | edit source]

Finally, there is the role that biochar can play in improving soil. This can happen by direct application of nutrients found in biochar, but also indirectly. Such benefits can be harnessed for greater agricultural productivity and more general soil rehabilitation of degraded or desertified terrain.

The current state of agriculture is far from sustainable. Heavy emphasis on monocultures leads to the mining of soil nutrients. Excessive use of inorganic fertilizers run the risk of acidifying soil, in addition to extreme levels of surface runoff that pollute waters downstream, creating dead zones. Biochar alone will not solve these problems, but is an important component of a shift in direction.

During production, gases in organic material is burned off, leaving behind mostly carbon with a great deal of pore space and surface area.[19]As discussed above, these qualities enhance water holding capacity and cation exchange capacity, which in turn increase the availability of soil nutrients to plants. This gives longevity to the soil, and reduces the need for fertilizer use. Biochar can also increase the efficiency of soil biota. In addition, biochar gives a liming effect to the soil by raising pH, and increasing nutrient availability to plants.

The actual effects of biochar on soil are, as has been mentioned numerous times in this article, dependent on several factors:

- Feedstock used

- Application rate and combination with fertilizers

- Production conditions

- Soil type and associated microbial community

- Crops grown

Thus, it is nearly impossible, at this point, to *predict* the effects of biochar on soils. Characterization of biochar remains an incredibly important task for the purposes of defining relevant properties and enabling communication about various types. Feedstock properties that are important to consider include:[2]

- Proportion of organic components, including lignin, cellulose, and others

- Proportion of inorganic compounds

- Proportion of non-biomass materials

- Bulk, true density, porosity and pore-size distribution

- Particle size distribution

- Strength in compression and tension

- Moisture content

Of these, to simplify classification, four parameters have been proposed:[2]

- Contents of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and labile and stable fraction of total C

- Composition by other elements

- Surface area and pore-size distribution

- pH and cation exchange capacity

Parameters of biochar production, enumerated briefly above, need to also be recorded and documented.

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Due to the wide variety of conditions that lead to biochar production, numerous effects, both positive and negative, have been reported. Effects for agriculture are primarily in terms of improved yield. Measures of soil nutrients, water-holding capacity and pH are also important. Numerous tests have been conducted with biochar, and the effects on crop yields have been recorded. Some reasons given for improvements are:[2]

- Water-holding capacity

- Black color on temperature

- Increased N uptake

- Retained fertilizer

- Maintained pH

- Improved nutrition of nutrients such as P, K and Cu

- Increase in P and N availability

- Improving physical properties of hard-setting soil

- Liming effect (increase in pH)

Some reasons for yield reductions are:

- pH-induced micro-nutrient deficiency

- Change in soil properties

A range of responses has been recorded for different parameters. Biomass, yield, tree density, height and volume are all potential descriptors of biochar response, but yield is likely the most widely applicable. A range of responses in yield are known, from a reduction of 71% to an increase of as much as 880%.[2]

Another review of crop responses to biochar applications found the following results:[20]

- An average increase of 10% on crop production, with a range from 55% decrease to 65% increase in crop productivity

- Modest improvements for acidic and neutral soils (14% and 13%, respectively)

- Similar improvements for coarse and medium texture soils (10% and 13%, respectively)

The wide range of operating conditions and data recorded in the tests reviewed point to the need for recording and communicating the maximum amount of information possible. This will help researchers analyze the effect of various details.

Recommendations[edit | edit source]

Given biochar's tremendous potential to alleviate climate change, increase agricultural productivity, utilize waste effectively, and generate energy, it is essential to learn as much about it and the best ways to use it as possible. Some steps to encourage this include:

- Developing a universal classification system of biochars

- Developing a standard set of data to collect during biochar tests

- Limiting the pollution-producing tendencies of biochar reactors, while maintaining simplicity and availability for small-scale farmers and ensuring recovery of byproducts

- Conducting tests for biochar over a wide range of pyrolysis conditions - temperature, heating rate, pressure, etc.

- Evaluating which crops respond best to different biochar applications, to make these results as relevant as possible for small-scale farmers

Dissemination[edit | edit source]

Numerous groups are promoting and supporting the use of biochar. Some of these include:

- International Biochar Initiative (IBI) - The leading source of information on biochar, IBI disseminates biochar information, in addition to developing sustainability guidelines and monitoring biochar projects. [1]

- Biochar Farms - The mission of Biochar Farms is to gather and share reliable information about biochar. [2]

- Biochar Discussion List - This website has a host of discussions about various aspects about biochar - producing and purchasing biochar, on-going research, etc. [3]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Lehmann, Johannes, and Stephen Joseph. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology. London: Earthscan, 2009. Print.

- ↑ Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State. Part 1: Literature Review of Pyrolysis Reactors. First project Report. Department of Biological Systems Engineering and the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and natural Resources, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. 137 pp.

- ↑ Hurd, Charles Dewitt. The Pyrolysis of Carbon Compounds,. New York: Chemical Catalog, 1929. Print.

- ↑ Baldock JA and Smernik RJ. 2002, 'Chemical composition and bioavailability of thermally altered Pinus resinosa (Red pine) wood', Organic Geochemistry 33: 1093-1109.

- ↑ Trompowsky, P. M., V. d. M. Benites, et al. (2005). "Characterization of humic like substances obtained by chemical oxidation of eucalyptus charcoal." Organic Geochemistry 36(11): 1480-1489.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Liang, B., J. Lehmann, et al. (2006). "Black Carbon Increases Cation Exchange Capacity in Soils." Soil Science Society of America Journal 70(5): 1719-30.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 (Major, J., M. Rondon, et al. (2010). "Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Colombian savanna oxisol." Plant and Soil 333(1-2): 117-128.)

- ↑ Anderson, C. R., L. M. Condron, et al. (2011). "Biochar induced soil microbial community change: Implications for biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus." Pedobiologia 54(5-6): 309-320.

- ↑ Rondon, M. A., J. Lehmann, et al. (2006). "Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with bio-char additions." Biology and Fertility of Soils 43(6): 699-708.

- ↑ Argyropoulos, Dimitris S. Materials, Chemicals, and Energy from Forest Biomass. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 2007. Print.

- ↑ Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web.

- ↑ Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State. Part 1: Literature Review of Pyrolysis Reactors. First project Report. Department of Biological Systems Engineering and the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and natural Resources, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. 137 pp.

- ↑ Bridgwater, A. (2007) 'IEA Bioenergy Update 27: Biomass Pyrolysis', Biomass and Bioenergy, vol 31, ppI-V

- ↑ Garcia-Perez, M., T. Lewis, and C.E. Kruger. 2010. Methods for Producing Biochar and Advanced Biofuels in Washington State. Part 1: Literature Review of Pyrolysis Reactors. First project Report. Department of Biological Systems Engineering and the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and natural Resources, Washington State University, Pullman, WA. 137 pp.

- ↑ Kammen, D. M. and Lew, D. J. (2005) Review of Technologies for the Production and Use of Charcoal, Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory, Berkeley University, 1 Mar. 2005. Web. 22 Apr. 2012. http://web.archive.org/web/20110913105616/http://rael.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/very-old-site/Kammen.charcoal.pdf

- ↑ Bates, Albert K. The Biochar Solution: Carbon Farming and Climate Change. Gabriola Island, B.C.: New Society, 2010. Print.

- ↑ Ackerman, F. (2000) 'Waste management and climate change', Local Environment, vol 5, pp223-229.

- ↑ Hottle, Ryan D. "Biochar Farms." Biochar Farms. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.

- ↑ Jeffery, S., F. G. A. Verheijen, et al. (2011). "A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application to soils on crop productivity using meta-analysis." Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 144(1): 175-187.

- Brewer, C. E., R. Unger, et al. (2011). "Criteria to Select Biochars for Field Studies based on Biochar Chemical Properties." BioEnergy Research 4(4): 312-323.

- Bruun, E. W., H. Hauggaard-Nielsen, et al. (2011). "Influence of fast pyrolysis temperature on biochar labile fraction and short-term carbon loss in a loamy soil." Biomass and Bioenergy 35(3): 1182-1189.

- Demirbas, A. (2004). "Effects of temperature and particle size on bio-char yield from pyrolysis of agricultural residues." Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 72(2): 243-248.

- Demirbas, A. (2007). "Bio-fuels from Agricutural Residues." Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 30(2): 101-109.

- Duku, M. H., S. Gu, et al. (2011). "Biochar production potential in Ghana—A review." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15(8): 3539-3551.

- Kammann, C. I., S. Linsel, et al. (2011). "Influence of biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa Willd and on soil–plant relations." Plant and Soil 345(1-2): 195-210.

- Karhu, K., T. Mattila, et al. (2011). "Biochar addition to agricultural soil increased CH4 uptake and water holding capacity – Results from a short-term pilot field study." Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 140(1-2): 309-313.

- Koide, R. T., K. Petprakob, et al. (2011). "Quantitative analysis of biochar in field soil." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43(7): 1563-1568.

- Lehmann, J., J. Gaunt, et al. (2006). "Bio-char Sequestration in Terrestrial Ecosystems – A Review." Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 11(2): 395-419.

- Li, D., W. C. Hockaday, et al. (2011). "Earthworm avoidance of biochar can be mitigated by wetting." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43(8): 1732-1737.

- Noguera, D., M. Rondón, et al. (2010). "Contrasted effect of biochar and earthworms on rice growth and resource allocation in different soils." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42(7): 1017-1027.

- Smith, J. L., H. P. Collins, et al. (2010). "The effect of young biochar on soil respiration." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42(12): 2345-2347.

- Song, W. and M. Guo (2011). "Quality variations of poultry litter biochar generated at different pyrolysis temperatures." Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis.

- Steinbeiss, S., G. Gleixner, et al. (2009). "Effect of biochar amendment on soil carbon balance and soil microbial activity." Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41(6): 1301-1310.

- Uzoma, K. C., M. Inoue, et al. (2011). "Effect of cow manure biochar on maize productivity under sandy soil condition." Soil Use and Management 27(2): 205-212.

- Van Zwieten, L., S. Kimber, et al. (2009). "Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility." Plant and Soil 327(1-2): 235-246.

- Warnock, D. D., J. Lehmann, et al. (2007). "Mycorrhizal responses to biochar in soil – concepts and mechanisms." Plant and Soil 300(1-2): 9-20.